14 February 2019

Pierre Bonnard – The Colour of Memory

Tate Modern (23 January – 6 May 2019).

Reviewed by William Morton

Nothing particularly staggering happened in Pierre Bonnard’s life (1867- 1947). He dabbled with women a bit but eventually married his long-term partner, Marthe de Méligny, to whom he seems to have been genuinely devoted. Until shortly before the Second World War, he had a house in Normandy close to Giverny and visited Monet regularly. He owned a second house at Le Cannet in the South of France where he lived for the rest of his life after selling his Normandy one. In a short film in the Exhibition, he appears an unassuming and amiable person. It would seem he liked animals, judging from the fact that they often appear in his pictures.

When he was young, Bonnard was, with Édouard Vuillard, a member of Les Nabis, a group of artists who aimed to produce symbolic and spiritual works. He did not usually paint from life but from memory with the aid of sketches and photographs and often continued to work on paintings over a long period. In an extreme case, Young Women in the Garden (probably of his mistress, Renée Monchaty, and Marthe) was originally painted in 1921-1923 and re-worked in 1945-1946 after Marthe had died.

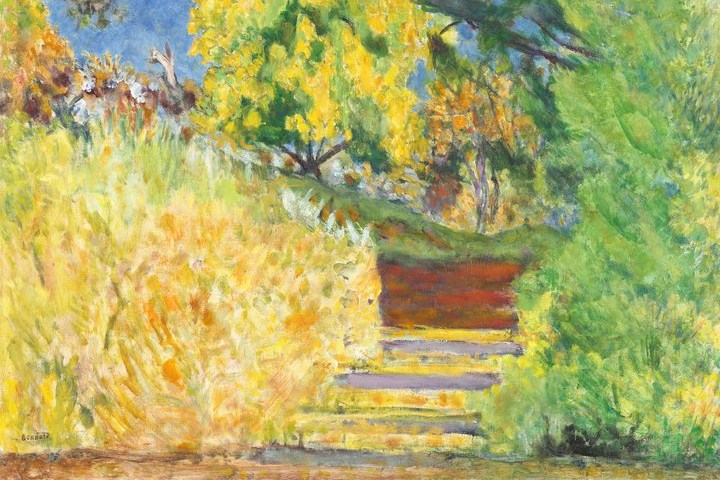

It is probably for his use of colour that Bonnard is best known and the Exhibition shows why. Stairs in the Artist’s Garden is a blaze of yellow and conveys the heat of summer in Provence. Views from his house with a glimpse of the Seine in the distance use a large range of colours but without a clash. Two paintings of the same scene, The Open French Window, Vernon, create a very different effect through the use of different colours.

His main subjects are his houses, their gardens, domestic scenes and nudes of Marthe. Although the settings are intimate, there is a detachment and a certain mystery as, for example, in Nude in an Interior where only part of the woman’s body is visible by an open door. However, these were not his only subjects. The Sunlit Terrace has a claustrophobic feel about it, which may well allude to restrictions resulting from the Second World War. In A Village in Ruins near Ham, French troops shelter behind the wall of a ruined cottage (interesting to see they were still wearing blue greatcoats in 1917). A Man and a Woman is a no-nonsense bedroom scene.

Rather surprisingly, Bonnard has always attracted a high level of criticism. Immediately after his death, he was defended by Matisse as a great artist when he was accused of being insipid and Impressionism in decline. Picasso was not a fan, saying that he was not a modern painter. Current critics who have been to the Exhibition have rushed to join in giving him a kicking (see Waldemar Januszczak of the Sunday Times ‘Too many marks. Too many colours. Too little sense of direction’, Adrian Searle of the Guardian ‘Everything was absolutely lovely. I couldn’t wait to get away’). I have even seen him attacked on the basis that his art took no great account of the First World War (he was 46 when it broke out) or the Second ( he was 70 when it started). Bonnard is, however, very popular with the general public and deservedly so. As exemplified by the Exhibition, his work is striking, colourful, individual and approachable and one would be very happy to own one of his paintings. Perhaps that popularity is the problem for his critics.