04 April 2019

Being Mortal*

And associated problems.

By Lynda Goetz

Being human, and without the benefit of any religious beliefs, I am not too keen on the idea of death. However, nor have I ever been very enthusiastic about the idea of immortality; particularly the sort envisaged by Jonathan Swift in Gulliver’s Travels. For those who have never read it or did so a good while ago (it was written, of course, nearly 300 years ago), Gulliver, apart from encountering the Lilliputians, came across the ‘struldbrugs’ (or ‘struldbruggs’) in the land of Luggnagg. They appear to be normal humans, but are in fact immortal. The downside is that they continue aging, so do not enjoy immortality with eternal youth. More recent science fiction has often promoted the idea of switching bodies as the way forward (e.g. Altered Carbon by Richard K Morgan) an idea possibly first postulated in fiction in H G Wells’s short story, The Story of the Late Mr Elvesham. That route has its own problems, as that story makes clear.

Being human, and without the benefit of any religious beliefs, I am not too keen on the idea of death. However, nor have I ever been very enthusiastic about the idea of immortality; particularly the sort envisaged by Jonathan Swift in Gulliver’s Travels. For those who have never read it or did so a good while ago (it was written, of course, nearly 300 years ago), Gulliver, apart from encountering the Lilliputians, came across the ‘struldbrugs’ (or ‘struldbruggs’) in the land of Luggnagg. They appear to be normal humans, but are in fact immortal. The downside is that they continue aging, so do not enjoy immortality with eternal youth. More recent science fiction has often promoted the idea of switching bodies as the way forward (e.g. Altered Carbon by Richard K Morgan) an idea possibly first postulated in fiction in H G Wells’s short story, The Story of the Late Mr Elvesham. That route has its own problems, as that story makes clear.

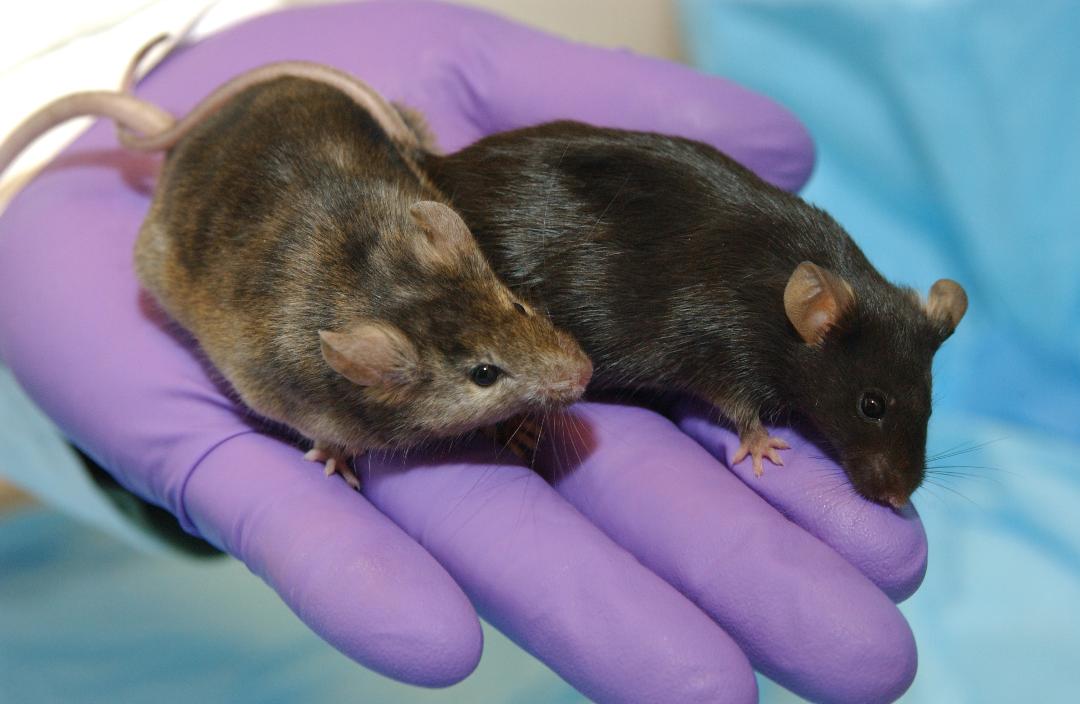

For a number of years now there have been periodic announcements about scientists making progress in finding the key to unlock the mystery of aging and there are already on the market plenty of beauty products which promise to ‘restore youthful looks’ or maintain ‘young-looking’ skin. Some of these products do help, but effectively on only a superficial level, and the aging process – believed to be responsible for many conditions such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, arthritis, cancer, heart disease and diabetes – has hitherto not been stoppable. This week, however, it was revealed in the mainstream press that the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota is actually trialing a group of drugs known as ‘senolytics’ in humans, having successfully slowed or reversed the aging process in laboratory mice.

Senolytics are anti-aging drugs which apparently work like broad spectrum antibiotics, alleviating or even preventing age-related illnesses and frailty. In mice, the drugs have extended their life span by 36 percent, the equivalent of about 30 years in humans. Six trials are currently underway in humans with six more planned. The drugs target senescent cells, also known as ‘zombie cells’. These form from normal cells which have stopped dividing but which, instead of dying and being cleared away, start pumping out damaging chemicals that cause harm to normal cells. As the name suggests, senescent cells build up with age. If these cells are transplanted into young animals, those animals begin to age and start developing age-related diseases. These effects can, however, be reversed with senolytics. It was even demonstrated recently that in human tissue samples taken from obese diabetics, the senolytic drugs made the fat cells sensitive to insulin again.

Senolytics are anti-aging drugs which apparently work like broad spectrum antibiotics, alleviating or even preventing age-related illnesses and frailty. In mice, the drugs have extended their life span by 36 percent, the equivalent of about 30 years in humans. Six trials are currently underway in humans with six more planned. The drugs target senescent cells, also known as ‘zombie cells’. These form from normal cells which have stopped dividing but which, instead of dying and being cleared away, start pumping out damaging chemicals that cause harm to normal cells. As the name suggests, senescent cells build up with age. If these cells are transplanted into young animals, those animals begin to age and start developing age-related diseases. These effects can, however, be reversed with senolytics. It was even demonstrated recently that in human tissue samples taken from obese diabetics, the senolytic drugs made the fat cells sensitive to insulin again.

This week is actually National Diabetes Week, and to raise awareness of the NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme, figures were released showing that ‘one new Type 2 diabetic is diagnosed every 3 minutes in England and Wales’. Horrendous as this may sound, these statistics from 2017 are actually a slight improvement on the previous year; nevertheless 4.7 million people are currently living with diabetes and this figure is expected to rise to 5.5 million by 2030. According to Chris Askew, Chief Executive at Diabetes UK, “three in five cases of diabetes can be prevented or delayed by eating well, being active, achieving a healthy weight, meaning there is hope for the future.”

More hope perhaps than he had believed, if the Mayo Institute’s findings are correct. But at what cost? Is this the point at which we stop encouraging the healthy living and just say ‘well, we can give you the drugs’? Who will pay for these drugs? Are they likely to become the preserve of the rich worldwide? In the UK, will they be generally available at whatever cost on the NHS, or should people have to make that effort towards healthy living before resorting to drugs? Could the NHS even begin to afford the cost? The difficulty with science, understandably, is that those practising it seek to extend the boundaries of human knowledge, but in so doing they by and large do not feel that it is their concern to examine the ethics or the consequences. Those issues are for others to wrestle with.

So if longevity – if not immortality – is within our grasp, what might be the consequences and how are we to deal with them? At what point do we start administering the age-defying drugs? Clinical geriatrician, Dr James Kirkland, director of the Robert and Arlene Kogod Centre on Aging at the Mayo Clinic+, said “Most people don’t want to live to 130 and feel like they’re 130 but they wouldn’t mind living to 90 and feeling like they’re 60.” The editorial in The Telegraph suggested that they might prefer to feel like they’re 20! Leaving aside the life stresses of being 20, where does this leave us? Administering the age-defying drugs at 20, 30, 40 or 50? Presumably it is going to depend on finances. So could this be the beginning of yet another societal divide? Can you afford those age-defying drugs and for how long can you afford to pay for them? Throughout your life, effectively; or simply from your 50s or 60s? So the wealthy can be young for decades, whereas the rest can either not afford to start paying for them until much later or possibly not at all.

This ‘good news’ about senolytics is thus fraught with difficulties, as we can see the minute we stop to consider it. Like so much human interference in nature it carries with it inherent problems, difficulties and inequalities which will almost certainly not be addressed until it is too late. Who should be addressing them? Governments? National ethics committees? Supranational ethics committees?Perhaps, in fact, our scientific and research focus really should be on the health of the planet – to allow generations of humans, other animals and organisms the chance of a normal lifespan, never mind ‘superhumans’ who can extend their lifespan to the detriment of new generations and other living creatures on Our Planet** Earth.

This ‘good news’ about senolytics is thus fraught with difficulties, as we can see the minute we stop to consider it. Like so much human interference in nature it carries with it inherent problems, difficulties and inequalities which will almost certainly not be addressed until it is too late. Who should be addressing them? Governments? National ethics committees? Supranational ethics committees?Perhaps, in fact, our scientific and research focus really should be on the health of the planet – to allow generations of humans, other animals and organisms the chance of a normal lifespan, never mind ‘superhumans’ who can extend their lifespan to the detriment of new generations and other living creatures on Our Planet** Earth.

* The title of a highly recommended book by Atul Gawande

+ (referencing The Sackler Effect article last week, I wonder how much they paid to get their name on that building – what was the source of that money?)

** New Netflix series starting on Friday 5th April, produced by Alistair Fothergill (responsible for Planet Earth on BBC) and narrated by David Attenborough.