04 April 2019

House Price Protection

Stress-free home ownership?

By Frank O’Nomics

Are you worried about a bear market for house prices? You probably should be. If a recession is defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth, then that is where the London property market is after seven successive falls. It is not just the southeast – the latest data shows the first quarterly annualised fall in UK house prices in seven years. For those who own property valued over 7 figures, this state of affairs has been in evidence for some time, and many boroughs of London have seen in corrections in excess of 25%. Older owners will remember the sharp property price crashes of previous decades which, if repeated, would put many into situations of negative equity, where their property is worth less than their mortgage. Others may have more than enough equity but have been looking to release some of it to fund their retirement. For them the nest egg looks distinctly threatened. But stop – this issue is one of the fundamental assumptions that one’s home is an investment, rather than just somewhere to live. What if we take the investment element out of consideration altogether? One eminent economist, Robert Shiller, is suggesting exactly that.

Are you worried about a bear market for house prices? You probably should be. If a recession is defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth, then that is where the London property market is after seven successive falls. It is not just the southeast – the latest data shows the first quarterly annualised fall in UK house prices in seven years. For those who own property valued over 7 figures, this state of affairs has been in evidence for some time, and many boroughs of London have seen in corrections in excess of 25%. Older owners will remember the sharp property price crashes of previous decades which, if repeated, would put many into situations of negative equity, where their property is worth less than their mortgage. Others may have more than enough equity but have been looking to release some of it to fund their retirement. For them the nest egg looks distinctly threatened. But stop – this issue is one of the fundamental assumptions that one’s home is an investment, rather than just somewhere to live. What if we take the investment element out of consideration altogether? One eminent economist, Robert Shiller, is suggesting exactly that.

In a research paper in The Journal of Derivatives, Mr. Shiller and his co-authors suggest that when a mortgage is sold the borrowers should be allowed to link their property to a financial product that would hedge against any losses during a financial crash. This product would be a derivative that would rise in value as property prices fell, thereby insulating the purchaser against the nightmare of negative equity. If taken up on a widespread basis this could potentially take away the risks of a financial crash similar to that of 2008, and would calm many market commentators who see the recent rise of personal indebtedness as creating exactly that kind of risk. Such a move could fundamentally change the mindset that getting on to the property ladder was essential given that, over the longer-term, house prices have always risen.

If you assume that housing, like any other asset, should over time grow at no more that nominal wage growth, these property derivatives can protect against the sharp corrections that inevitably follow a period of above-trend growth. Further, it will encourage the thought that housing is actually a wasting asset, the quality of which will deteriorate over time unless resources are expended (on redecoration, plumbing, roofing, rewiring etc.). This should not discourage those who want to earn a return as landlords, but that return will be one of rental income rather than a capital return from price growth. If anything, a more stable price environment should encourage people to own property for income.

There are, however, a number of problematic issues with the analysis in Shiller’s Paper. In previous works he has talked about the American process whereby, following movements of population towards an urban centre, and the driving up of property prices, there quickly develops an incentive to build a new city where property will be cheaper. This pressure means that there is an ultimate cap on property price rises, and describes much of the development of California in particular. For the UK the situation has historically proved somewhat different. While New Towns, such as Milton Keynes, have been developed, the limitations on building in the southeast, and the decline of the industrial north, have yet to stimulate the development of new cities. Arguments citing the availability of sufficient land may be hard to support (only 6% of land in the UK has so far been built on) but the rise of property prices has been (beyond those nasty corrections) relentless, with the ripple effect from the southeast permeating everywhere ultimately.

What will discourage many from taking up any property protection, if they are not forced to by regulations, is the fact that by eliminating the downside, they will also negate the upside given the cost of buying protection. Hitherto, even the creation of commercial property derivatives (which have existed for many years) has seen only modest interest from those pension and insurance funds whom, one would assume, would have liked to eliminate the price volatility of their investments. There have been many problems, including costs (which could be prohibitive), and effectiveness – there is always the danger that the prices of such products fail to behave as they are assumed to. This would then push the lending institutions into yet another round of mis-selling claims – just when they are escaping PPI and swaps compensation payments.

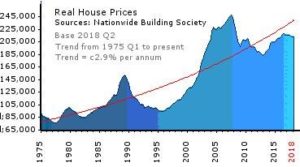

The final reason why the initiative suggested by Robert Shiller and colleagues is unlikely to develop soon is that we have a whole industry that thrives on inexorable property price growth, and for the last 45 years the trend real price growth has been 2.9% per annum.

Looking at this graph, we are actually somewhat below that long-term trend rate and, unless that trend changes, many will argue that house prices are cheap (although this is hard to do on affordability grounds) – so why would they want to spend money protecting against a price fall?

Looking at this graph, we are actually somewhat below that long-term trend rate and, unless that trend changes, many will argue that house prices are cheap (although this is hard to do on affordability grounds) – so why would they want to spend money protecting against a price fall?

Robert Shiller has long argued against the myth that the price of real estate must trend strongly upward over time. We currently face a very vulnerable UK property market, with affordability, stamp duty, fading international buyers and Brexit concerns all undermining support. Taking the risk and volatility out of something so fundamental as having somewhere to live is a very attractive proposition – particularly when those risks create an even greater threat for the economy overall. Consider those living in Northern Ireland, for example, where property prices are still 1/3 lower than their peak in 2007 – price protection here would have proved very effective. However, while recent work on property derivatives pricing methodology may make a more effective product a reasonable possibility, getting the financial and building industries to support it is still a very long way off.