16 April 2020

Will Covid-19

change the French?

By Richard Pooley

A year and a day ago the roof of Notre Dame in Paris caught fire. “You learn a lot about a people’s culture when they are hit by a disaster, natural or man-made” was the opening sentence of my commentary Notre Dame on this awful event.

I am confiné chez nous in a village of some 1300 souls in south-west France, although chez moi would be more accurate. My wife is in the UK; so I am célibataire to boot. Feel no sympathy. I may be on my own but I can walk to five food shops, a pharmacy, and a newsagent/tobacconist, all of which are open for a reduced number of hours. Our mayor begged the préfet in Cahors, the departmental capital, for our Thursday and Saturday markets to remain open. He agreed. Our village is one of only six in the Lot Department given such dispensation. I am following Voltaire’s advice for what to do in troubled times and tending my garden, sowing vegetables and fruit in the full expectation that I will be harvesting them. I can go jogging through village and woods for, I calculate, up to 8.4 kilometres, provided I am never more than one kilometre from my domicile (tip: use pi when doing the math). I am in one of the most lightly-populated parts of France. Which may partly explain why the Lot had, up to yesterday, had just four deaths due to Covid-19 out of the 15,729 that have occurred nationally. And why the trains which have been converted into Covid-19 patient-carriers have been hurtling into south-west France from the north and east over the past ten days. And why many Parisians fled south to their family homes shortly after the lockdown and before the police started blocking exit routes out of the capital. Friends and family implored me to get back to the UK “before it’s too late”. My reply – “It’s not 1940, you know” – did not reassure them.

So, what changes have I seen in the behaviour and attitudes of my French friends and neighbours?

I expected them to find social distancing a trial. The gap here is one metre (though our village market insists on one and a half metres). Brits are supposed to think of holding out a broom to give them an idea of what two metres are. How many Brits have ever even held a broom? The guide in France is much better: the traditional baguette, which by law must be no less than 65cm long. The British image of the French – arm-waving, finger-pointing, hand-shaking, kissing and hugging – were all on show when I was walking past students, celebrating the end of term, alongside the Garonne river in Toulouse on Friday 13th March. The French lockdown – confinement sounds more comforting to an English ear – started at midday on Tuesday 17th March. The next day I witnessed a first for me in France: silent, orderly queues, each person a metre apart, outside one of the village’s boulangeries, the farmers’ coop shop, and the pharmacy. And so it has continued for over four weeks. Nobody seems the slightest bit unhappy about it. Why so?

I expected them to find social distancing a trial. The gap here is one metre (though our village market insists on one and a half metres). Brits are supposed to think of holding out a broom to give them an idea of what two metres are. How many Brits have ever even held a broom? The guide in France is much better: the traditional baguette, which by law must be no less than 65cm long. The British image of the French – arm-waving, finger-pointing, hand-shaking, kissing and hugging – were all on show when I was walking past students, celebrating the end of term, alongside the Garonne river in Toulouse on Friday 13th March. The French lockdown – confinement sounds more comforting to an English ear – started at midday on Tuesday 17th March. The next day I witnessed a first for me in France: silent, orderly queues, each person a metre apart, outside one of the village’s boulangeries, the farmers’ coop shop, and the pharmacy. And so it has continued for over four weeks. Nobody seems the slightest bit unhappy about it. Why so?

I’ve always felt the whole kissing (one, two, three, oh no, not four, surely?) and hand-shaking routine in France to be theatre. It’s really a power battle: see, I’m in control here. I will allow you two kisses. Notice how firm my handshake is. I am self-confident. Are you? It’s the outward expression of that fundamental tenet of French culture: individualism. If it is clearly in my own self-interest to keep my distance from you, I shall do so.

Likewise queueing. The norm when shopping in France at a market or, say, boulangerie, is to get as close to the front of the knot of waiting customers as possible and make sure the person serving has noticed you: I’m here, Madame. Me, me. Not for the past four weeks. Stay away from me. I trust Madame to know I was here before you.

But what about Fraternité, you ask? What about it? Liberté comes before it. I must have the freedom to do what I want to do.

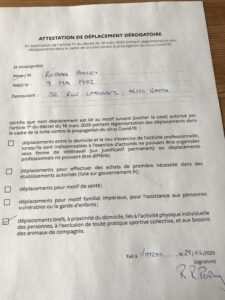

There is a paradox here, of course. The French pride themselves on being individualists yet most appear to have immediately and consistently obeyed the rules of the lockdown issued by their government. The key words in that sentence are “appear to”. I went on the Ministry of Interior’s website on the morning of 17 March and read on what five grounds I would be allowed to leave my house during the confinement. It also said that the site would soon publish the document – the attestation de déplacement dérogataire – which every person must fill in and carry with them whenever they leave their house. If you don’t have a printer, you can write it out longhand. The attestation process suits the French mind-set. I fill it in, giving my name, age, address, and sign and date it. I decide which of the five options to tick (one per document). And, crucially, I decide what each option really means. The document has become a little more specific in the past month as to what one can and can’t do but there are still enough grey areas to allow for debate as to what each option really means. Debate?

Ah, yes. With a policeman? Even better.

I have had one brush with the police. I was driving back into the village from the supermarket on its edge, full basket and ticked attestation on the front passenger seat, when I saw two policewomen running a checkpoint. I joined the back of the car queue, smug in the knowledge that I had obeyed the rules. Too late I spotted that I had picked up the wrong attestation, the one where I had ticked the box for taking exercise. I scrabbled for a pen but ended up with two ticked boxes. The policewoman barked an order which I failed to understand. She came round to the passenger side and I lowered the window. “Non!” she screamed. I raised the window and she peered at the document. A ticking off followed. It was day 3 of the lockdown and already fines for disobedience had tripled. I used the old expat get-out-of-jail card: “Je suis anglais” and told her that I had made a mistake and ticked the wrong box, blah, blah. She put her hand up to demand silence. A pause and then a big smile. “Allez-y!” I thought at the time that she had taken pity on the dumb foreigner. But on reflection, it was probably my very un-French admission of error. The Frenchman would have argued the toss. And got fined. But he would have reinforced his individuality and freedom to choose.

I have had one brush with the police. I was driving back into the village from the supermarket on its edge, full basket and ticked attestation on the front passenger seat, when I saw two policewomen running a checkpoint. I joined the back of the car queue, smug in the knowledge that I had obeyed the rules. Too late I spotted that I had picked up the wrong attestation, the one where I had ticked the box for taking exercise. I scrabbled for a pen but ended up with two ticked boxes. The policewoman barked an order which I failed to understand. She came round to the passenger side and I lowered the window. “Non!” she screamed. I raised the window and she peered at the document. A ticking off followed. It was day 3 of the lockdown and already fines for disobedience had tripled. I used the old expat get-out-of-jail card: “Je suis anglais” and told her that I had made a mistake and ticked the wrong box, blah, blah. She put her hand up to demand silence. A pause and then a big smile. “Allez-y!” I thought at the time that she had taken pity on the dumb foreigner. But on reflection, it was probably my very un-French admission of error. The Frenchman would have argued the toss. And got fined. But he would have reinforced his individuality and freedom to choose.

I mentioned that the French appear to be following the rules. Welcome to another cornerstone of French culture: Système D. This is the skill of finding ways around a problem, often created by bureaucrats and politicians, and coming out on top. D comes from either débrouillard or démerdard. I prefer the latter adjective, used to describe someone who knows how get himself out of the shit. George Orwell wrote in Down and Out in Paris and London that his fellow dishwashers in early 1930s Paris prided themselves on being débrouillard.

Here’s an example of Système D from many I have observed. The garden centre just outside our village, part of a national chain, also sells outdoor clothing, diy products, food and wine. The latter two enables it to stay open, although all the rest of its goods are interdit, out of reach behind lines of tape and pallets. Except seed potatoes, onion sets and vegetable seeds. I asked on what basis they were still selling these. “Food for the future”. I admired their logic (and the poetry of the original French). On a subsequent visit I noticed that they were also selling flower bulbs. “Nourriture pour l’esprit?” I asked. After a pause, no doubt to work out my clumsy French, they laughed and agreed that that was the reason.

I see no sign that this virus is changing French culture in any meaningful way. I doubt if it is doing so anywhere else. Instead each country is revealing its culture in the way that it tackles the crisis. But what will change long-held attitudes and long-settled behaviour here and around the world is the economic storm which Covid-19 has brought in its wake.