14 November 2019

Tutankhamun

The Saatchi Gallery

reviewed by Adam McCormack

King Tut is back and this could be his farewell (and best) gig ever. The recently opened exhibition of the treasures of Tutankhamun at the Saatchi Gallery displays the largest collection of artifacts ever exhibited in one place outside Egypt, many of which have never previously left the country. Given that a new Grand Egyptian Museum is being built in Cairo to house the whole collection, it seems unlikely that this opportunity will come along again.

King Tut is back and this could be his farewell (and best) gig ever. The recently opened exhibition of the treasures of Tutankhamun at the Saatchi Gallery displays the largest collection of artifacts ever exhibited in one place outside Egypt, many of which have never previously left the country. Given that a new Grand Egyptian Museum is being built in Cairo to house the whole collection, it seems unlikely that this opportunity will come along again.

What is so overwhelming about this exhibition is not the story behind the discovery of the hidden tomb in 1922, compelling though that is, and is not just the undoubted beauty, splendour and intricacy of the objects on display. The most compelling element here, helped by the manner and order in which the treasures are displayed, is the way in which it makes life in ancient Egypt seem so real to the modern visitor. We are given vivid descriptions as to why each item was important on a pharaoh’s journey to the Netherworld. To see the range of containers of food and wine, a pair of delicate gloves, a plethora of walking sticks (Tutankhamun had a clubbed foot) and a range of caskets for all the necessary possessions, takes us way beyond curiosity and much closer to empathy. Some of the wooden boxes could be confused with the items of a travelling Victorian gentleman, and the level of detail, such as writing on the wine containers the year and grower, are much more in keeping with modern norms than one would expect (who would have thought that pharaohs were wine snobs).

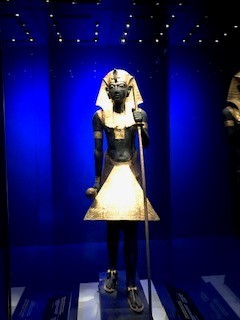

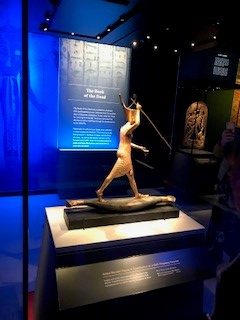

Nevertheless, the quality and beauty of the statues, jewelry and funeral trappings will be what impresses most. That such objets could be so well preserved after 3 thousand years is hard to believe and the level of detail, use of materials and exquisite workmanship would be hard to recreate even now. Visitors are given a set time to arrive to moderate numbers, but it would be a shame not to loiter to absorb all of the splendour and to listen to all of the narratives for each key exhibit. Of particular note is the range of body ornamentation, the finely crafted ceremonial crook and flagellum, and gilded statues featuring the boy king in the various endeavours expected on his afterlife journey.

If there is a criticism of this exhibition it is in the way we are led through the story. The telling of the key elements in the background to the discovery – the association of Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon and the water boy who found the first step to the entrance – are left until the final galleries. Starting with this and then letting us experience, in a similar manner to Carter, the startling revelation of the tomb’s contents might have enhanced the experience. From the curator’s perspective I can, however, see why you would not want to exhaust the viewer before the multiple big reveals.

If there is a criticism of this exhibition it is in the way we are led through the story. The telling of the key elements in the background to the discovery – the association of Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon and the water boy who found the first step to the entrance – are left until the final galleries. Starting with this and then letting us experience, in a similar manner to Carter, the startling revelation of the tomb’s contents might have enhanced the experience. From the curator’s perspective I can, however, see why you would not want to exhaust the viewer before the multiple big reveals.

The exhibition does take pains to undermine some of the myths. The curse on those who discovered the tomb is given short shrift and stories that the boy pharaoh was murdered are effectively disproved – a infection after a fractured femur, possibly from a chariot fall, in a young man already weakened by malaria seems the credible cause of death. The story telling does, however, allow speculation that the blowing of a trumpet found in the tomb has apparently heralded world conflict. Perhaps fortunately, the trumpet is now deemed too fragile to play.

The ancient Egyptians believed that we die twice. The first was the loss of our mortal life; the second was on the death of the last person to speak your name. Tutankhamen’s immediate successors expunged his name from public memorials and, without Carter’s discovery that would have been the end. The events of 1922 and exhibitions such as this will mean that he will live on for a few millennia yet.

The ancient Egyptians believed that we die twice. The first was the loss of our mortal life; the second was on the death of the last person to speak your name. Tutankhamen’s immediate successors expunged his name from public memorials and, without Carter’s discovery that would have been the end. The events of 1922 and exhibitions such as this will mean that he will live on for a few millennia yet.