3 December 2020

Lies, Damned Lies and Coronavirus

The Liverpool myth.

By David Chilvers

As forecast last week*, politicians have been quick to claim the impact that their policies have had on controlling the spread of COVID-19. There has been particular refence to the success of Tier 3 and mass testing in Liverpool, so much so that the Liverpool City region returned to Tier 2 on 2nd December.

As forecast last week*, politicians have been quick to claim the impact that their policies have had on controlling the spread of COVID-19. There has been particular refence to the success of Tier 3 and mass testing in Liverpool, so much so that the Liverpool City region returned to Tier 2 on 2nd December.

Prior to 22nd September, Liverpool was following national general guidelines relating to the Hands. Face, Space strategy to:

- Reduce human interaction via social distancing (Space)

- Reduce the impact of human interaction by the wearing of masks in places where social distancing is difficult, and indoors in shops (Face)

- Reduce the spread if someone picks up the virus, through hand and surface hygiene (Hands)

On 22nd September, Liverpool imposed a further restriction that “Residents must not socialise with other people outside of their own households or support bubble in private homes and gardens”.

From 17th October, Liverpool was put into the “Very High Alert” Tier 3 and on 5th November the second national lockdown commenced, covering all of England.

In the Downing Street briefing on 26th November, Boris Johnson said “Liverpool shows what can be achieved. In Liverpool, in the space of two and a half weeks, over 240,000 tests have been conducted and together with the effect of national restrictions, this has helped to reduce the number of cases in Liverpool City Region by more than two thirds.”

In the Times on 28th November, Michael Gove said “What has worked, however, is the combination of a toughened Tier 3 and widespread community testing. In Liverpool, the mayor Joe Anderson bravely adopted measures above and beyond the old basic Tier 3 and championed mass testing. The result: falling infections, reduced hospitalisations and a smooth transfer to the new Tier 2.”

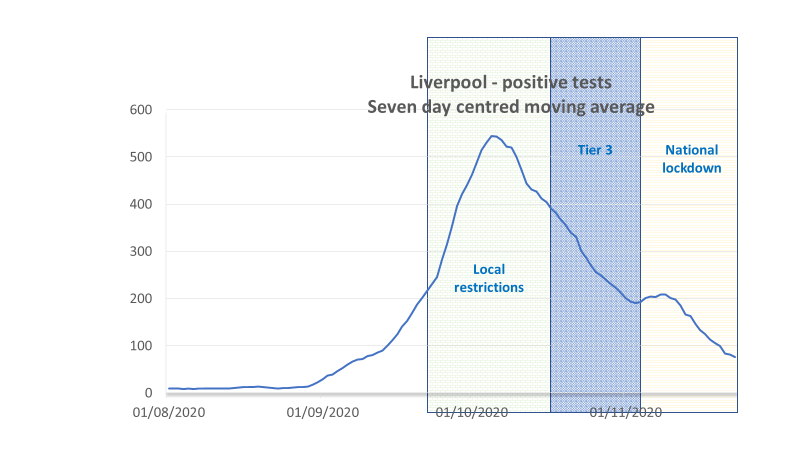

You might conclude from these two statements that Tier 3 and mass testing had been responsible for the reduction in the number of positive tests in Liverpool. However, nothing could be further from the truth, as the chart below clearly demonstrates:

The number of positive cases in Liverpool was on a downward trend two weeks before the city went into Tier 3. At the start of the national lockdown on 5 November, the mass testing programme commenced and you can see a fairly immediate but relatively small increase in the number of positive tests. This is what would be expected – testing 240k people with no symptoms is bound to add a relatively small number of positive cases to what would otherwise have been occurred. But apart from this small increase, the number of positive cases continues its steady downward trend.

Similar patterns exist in other Liverpool area local authorities – Halton, Knowsley, Sefton and the Wirral – with a slightly later peak in St. Helens.

The conclusions from the data on positive tests in Liverpool are that:

- During the period of local restrictions, including no mixing between households in private homes or gardens, the number of positive tests peaked and started to fall

- The number of cases was on a steep downward trend two weeks before Tier 3 commenced and following this the downward trend stayed on the same trajectory

- This downward trend continued (but did not accelerate) following the start of the national lockdown, although the impact of the mass testing in increasing the number of cases is clear

So, what factors were responsible for the turnaround in Liverpool, given it was clearly not due to either going into Tier 3 or the national lockdown?

We have two hypotheses:

- The existing restrictions of Hands.Face.Space plus no mixing between different households in private homes or gardens was working

- The stream of news about the infection returning made people more cautious, further restricting their contacts with others

With regard to the first hypothesis, the number of positive cases in Liverpool reached its peak on 5th October (using the centred seven day moving average). This is two weeks after the additional local restrictions were imposed and thus fits the timescale for when these might be expected to have an impact.

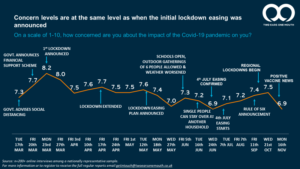

Looking at whether individuals were becoming more concerned about the renewed spread of COVID-19, the research agency Two Ears One Mouth runs a COVID Sentiment Tracker, with fieldwork at regular intervals but at times which try and avoid major news announcements (as these would cause particular spikes in the data). A key question on this tracking study asks consumers to rate how concerned they are on a scale of 1-10 about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on them. The chart below shows how the mean score on this question has changed over time.

There was a sharp rise in concern during the first wave in March, but this fell away quite quickly by early April. From July through to September, concern rose gradually to a mean of 7.4 on 11th September, when the Rule of Six was announced. The figure only increased slightly by 21st October when we were well into the original Tier system.

It does look from this data that consumer concern may be leading infection rates and thus lends support to the second hypothesis that during September people became more concerned about the impact of COVID-19 on them and may have restricted their contacts with others as a result (and so reducing transmission of the virus).

So, there is evidence supporting both of these hypotheses and the underlying conclusion is that once the basic rules about social distancing, mask wearing and hygiene are in place:

- Consumer concern about transmission may restrict interactions and the spread of the virus

- Consumer rules, such as the rule of six, may also restrict interactions and the spread of the virus

- Tiers and lockdowns*, restricting interactions by law and by partially or fully closing particular sorts establishments, have no great impact on the spread of the virus

If the spread of the virus is properly communicated and clear guidance regarding social interaction and infection control is publicised, consumers will respond – as they have – and the spread of the virus may be able to be controlled without resort to shutting down large parts of the economy.

*This article is one of a series, find last week’s article “Do Lockdowns Work?” here.