1 October 2020

The Great Debate

At Oxford Univ Museum of Natural History

by Philip Throp

This week, the OUMNH (Oxford University Museum of Natural History) re-opened its doors after a six month closure due to the pandemic. Originally opened in 1861, the building was used straightaway, before many of its exhibits were installed, for what became known as The Great Debate, the clash between representatives of the new Darwin theory of evolution and the representatives of the Established Church, whose Creation explanations the Darwinian Theories challenged.

Victorian Christians saw the bedrock of revelation as a duality, first God’s Word, and second His Natural Creation. The OUMNH displays have always been divided into two sections, a) the works of God (“natural elements”) and b), the “lesser” works, those of Man, displayed in the anthropological Pitt-Rivers section of the museum. The staff of the Pitt-Rivers have used the covid19 break to review and re-sort their collection, to de-colonialise it, and to offer “more modern” explanations of many of the objects they have retained.

The building was conceived in Victorian times to mark and facilitate the University’s jump into the study of the Sciences by intellectual, theoretical courses of study to a more evidential, observational approach, “Natural Sciences”, as the courses are still named. Many of the exhibits came from the old Ashmolean Museum’s collection, donated in the late 1600’s by Elias Ashmole, who had stipulated as a term of his gift that the University must provide a permanent building to house the collection he bequeathed. This building was purpose-built on Broad Street, next to the Sheldonian Theatre, the place for university ceremonies. It was the world’s first public-access museum, costing one penny to view the collection.

Ashmole “came by” the collection in an unusual way. Born in Lichfield in 1617, he became a solicitor. His Law training came in useful for him, as he was personally involved in 3 legal cases which marked the trajectory of his ambition.

His first wife Eleanor Mainwaring died in childbirth 3 years after their marriage. It had been an advantageous match but Ashmole had to fight her family in the courts to secure her income for himself. He was a staunch Royalist and, on becoming a courtier in the restoration of Charles ii, now made overtures to a number of rich widows. He finally married a Mrs Mainwaring (distantly related by an earlier marriage to his first wife Miss Mainwaring, though the two ladies did not know each other.) On their separation this second Mrs Ashmole sued him for alimony and divorce, but he successfully resisted her claims and obtained her fortune. Now rich enough to be a gentleman of leisure, Ashmole became a minor collector of curios, and befriended John Tradescant, a botanist and exotic plant-hunter. Tradescant brought back not only plants from his visits abroad but also indigenous objects. These “cabinets of curiosities” (hence why we call such items “curios” today) were highly fashionable at the time, and Trasdescant had a permanent exhibition of his collection attached to his home in London. Ashmole persuaded Tradescant to alter his Will to bequeath the collection to him, but following the death of the latter, Ashmole met fierce legal opposition from Tradescant’s wife, claiming falsification and duress in Tradescant’s Will. Ultimately Ashmole was successful in the lengthy court case. Just a few weeks after the conclusion of the court case, Mrs Tradescant was found dead, apparently drowned, in her garden fountain. The coroner concluded it was a suicide.

150 years on, by the early 1800s, the University’s collection of objects housed in the old Ashmolean Museum had outgrown the building, so some of the classical antiquities moved into the new Ashmolean museum and art gallery which was opening at the north end of the town centre, and items relevant to the study of natural sciences were moved into the also-new OUMNH. Confusingly, after a number of other intervening uses, the old Ashmolean eventually took its present form as the Museum of the History of Science.

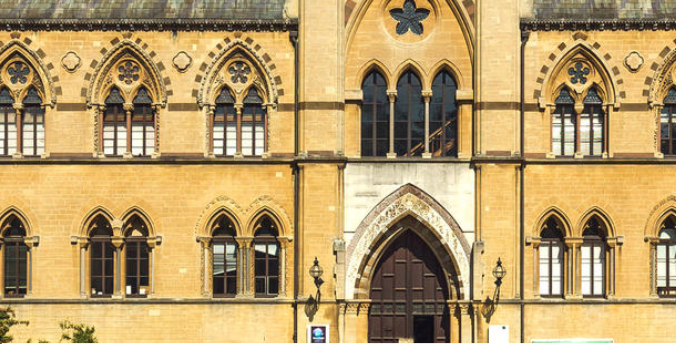

The actual construction of the OUMNH was fraught with difficulty, mainly because it was attempted to fund it by public subscription. The response was intermittent and inadequate, finally solved by the Oxford University Press turning over to the project the proceeds of its revenues from the sales of bibles, over which it held a monopoly. The sales were very significant at that time, thanks to the activities of the Oxford University-based “Tractarians”, (also known as The Oxford Movement), which put the Church of England at the centre of public attention by arguing against the unwelcome political interference of successive Governments and in favour of returning the C of E to pre-Reformation principles and ceremonial practices. This brought about the mass renovation and reconstruction of many churches, and explains why so many C of E church buildings look so much like each other today, by their return to Gothic architecture designs. And why the OUMNH building itself is in the same neo-Gothic style. It is often said to look like a Flemish town hall, or a railway station.

A French journalist viewing the Charge of the Light Brigade in 1854 had famously remarked: ‘C’est magnifique, mais ce n’est pas la GUERRE” (“but its not war”). Now 7 years later at the opening ceremony of the OUMNH, the French ambassador quipped: “C’est magnifique, mais ce n’est pas la GARE” (“but its not the railway station”).

The stone decorations of the building, both inside and out are still clearly unfinished, due to lack of finance. The architect employed two stone carvers, the O’Shea brothers, to carve and install the grotesques (gargoyles without an open mouth) on the front friezes, but even today these only go partway along. The brothers down-tooled in yet another interruption of their work and wages due to lack of funds and internal politics over the designs, but not before installing a series of parrots and owls grotesques parodying the faces of the members of the University Committee responsible for the project.

Centrally at the top of the arch to the front door there is a carving of an angel, holding in one hand a book with seals and in the other a living cell. Interestingly this was a diversion from the original design, in which the angel held two books, one in each hand, presumably old and new testaments, or possibly (see above) the two “books” (of The Word and of Creation). The University will have changed the design at this stage to show its evenhanded-ness to both the literal version and the pursuit of biology in the search for truth, the differing claims of which would be debated in the public debate to come.

In the debate the arguments of Church would be represented by the Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce, himself an eminent mathematician. He is a member of the House of Lords and son of the anti-slavery politician William Wilberforce. I think Disraeli did not like Samuel Wilberforce. (Have your Oxford Dictionaries at the ready, dear readers.) It does not sound to me like a term of endearment to describe a man as:“unctuous, oleaginous, saponaceous”. Unfortunately, the latter jibe was to stick with Samuel Wilberforce, evermore known as “Soapy Sam”. Darwin was not a man of powerful verbal presentation and sent along his young “bulldog” Thomas Huxley.

There were no minutes or verbatim accounts of the proceedings in the public debate, but it is best remembered today as becoming quite personal when the good Bishop asked his opponent if it was by his grandmother or his grandfather that Huxley was descended from a monkey. Huxley’s withering response, “I am not ashamed to have a monkey for an ancestor, but I would be ashamed to have as an ancestor a man highly endowed by nature and possessed of great means of influence who yet employs these faculties and that influence for the purpose of introducing ridicule into a great scientific discussion, then I unhesitatingly affirm my preference for the ape.” (quote).

Yah boo (unquote).