1 October 2020

Get Lewis

Newkie Noir.

By J.R. Thomas

Sometimes the Shaw Sheet tries to divert you from our troubling world (don’t worry too much, the world was ever thus) down some literary byway. There’s nothing like an anniversary to trigger this sudden descent from the highway and into the wilderness. This week we have found a triple anniversary to perhaps intrigue you.

Sometimes the Shaw Sheet tries to divert you from our troubling world (don’t worry too much, the world was ever thus) down some literary byway. There’s nothing like an anniversary to trigger this sudden descent from the highway and into the wilderness. This week we have found a triple anniversary to perhaps intrigue you.

It would have been the 80th birthday this year of Ted Lewis; the 50th anniversary of something which had a profound effect on Tyneside; and the 40th anniversary of a book which should have created a Chandleresque reputation, but which instead was forgotten for 35 years.

The coincidence of these anniversaries will have already given the game away to those who like their literature dark, those whose preferred different world is criminal, worrying, and sleazy. The link is Ted Lewis; it would have been his 80th birthday this year; it is the 50th anniversary of his best seller “Jack’s Return Home”, written when he was 29, and the 40th of his best book, “GBH”. Still struggling to place all this? “Jack’s Return Home” is better known as “Get Carter”, that iconic film of Tyneside in the 1960’s, all crime and corruption, violence and dolly birds, finally announcing the genius of Michael Caine. (Lewis adapted his own book, wrote much of the screen play, and was ever present on the set.) “GBH”, written ten years later, also attacks the same themes, but this time in London and in a fictional setting on Humberside that is clearly Mablethorpe. Two years later Lewis was dead, burned out by alcohol, living in Barton-on-Humber with his mother, broke, divorced, abandoned. His own life would indeed have made another great book if only he had survived to write it.

Some readers may still be floundering to place all this, although they will have led sheltered lives indeed if they have not watched “Get Carter”, at least on the small screen. So, the Lewis biography. Born in Manchester in 1940, an only child, his father was a shipbuilders clerk and his mother socially ambitious and highly possessive. Lewis liked to make out they were a working class family but the Lewis’s were solid lower middle class on their way up. In 1946 Lewis senior became manager of a quarry, moved to Barton-on-Humber, and bought a house in a middle class road, a three bedroomed semi. In due course Mrs Lewis got their son into Barton Grammar School. That sort of background was the foundation of Ted Lewis’s books, an endless fascination as to what went on behind the net curtains and manicured front gardens. But what Lewis was interested in was not respectable lives and middling careers, but sexual deviation, sleaze, crime, and violence, and what happened when respectability met the criminal mind.

Where did that come from? Lewis was ill in childhood which perhaps allowed him to develop a very vivid imagination, but also was mentored by his grammar school English master, Henry Treece, who believed in his early talent as a writer and story teller (and indeed as an artist), and encouraged it. (Readers may recall Henry Treece, who wrote many popular children’s historical novels.) Lewis, encouraged by Treece though not his parents, went on to Hull Art College, and then, as was almost commonplace in the 1950’s and 1960’s, drifted to London, and into advertising, then into film production and script writing. His true ambition was always to be a novelist and in 1965 he wrote his first novel. It was quite well reviewed but with a lack of anything particularly new to say did not sell well. He then went quiet, getting married, starting a family, and moving to unlikely rural Essex.

Unlikely, because Lewis was already fascinated by and becoming a part of the London Soho scene. Soho in the 1960’s was the centre of sex and lowlife living, a strange mixture of misfits, tarts, arty types, and crime. Fun for those who liked living on the edge, but undoubtedly dangerous. Lewis became very bound up in this world of vice and crime (it seems likely that is why he parked his family well away from it, in Essex). From it came the tale of a London crime gang and their executioner, Jack Carter, who returns to his hometown after the death of his brother, to seek the truth and a very messy vengeance. The town in the book was closely based on Barton-on-Humber’s neighbour, Scunthorpe, a booming steel town but with a layer of corruption. The film “Get Carter” moved the hometown to Newcastle, for filmic reasons, capturing the strange atmosphere of a major regional capital with immense political corruption, and that undercurrent of violence into which Carter sardonically steps.

Unlikely, because Lewis was already fascinated by and becoming a part of the London Soho scene. Soho in the 1960’s was the centre of sex and lowlife living, a strange mixture of misfits, tarts, arty types, and crime. Fun for those who liked living on the edge, but undoubtedly dangerous. Lewis became very bound up in this world of vice and crime (it seems likely that is why he parked his family well away from it, in Essex). From it came the tale of a London crime gang and their executioner, Jack Carter, who returns to his hometown after the death of his brother, to seek the truth and a very messy vengeance. The town in the book was closely based on Barton-on-Humber’s neighbour, Scunthorpe, a booming steel town but with a layer of corruption. The film “Get Carter” moved the hometown to Newcastle, for filmic reasons, capturing the strange atmosphere of a major regional capital with immense political corruption, and that undercurrent of violence into which Carter sardonically steps.

This theme of returning home was one that was common to his future books, his anti-heroes being men who have turned to violence, who are terrifying to those innocents who get in their way, are abusers of alcohol, and with sexual appetites that are certainly not those of the polite middle classes. It is a world beautifully observed, and you do not need to read too much Lewis to be persuaded that this was a world he had come to know uncomfortably well. How well, nobody can be sure, as he led a very secretive life in London, but he was certainly a frequenter of many clubs and bars where the more innocent would not have trodden.

“Get Carter” seemed to have made Lewis’s future secure; he was hailed as the leader of the Brit Noir movement, a Chandler or Hammett, updating their 1930’s world to a 1960’s one, with the Humber estuary standing in for the Californian Pacific (most of his work has a Humberside connection). But something went wrong; he wrote two rather pot-boiler (but what a talented pot-boiler he could be) prequels to “Get Carter” – no spoilers here, go read them; then “Plender” about a villain from Barton psychologically undermining a successful former school hero. “Plender” is a great book, but what came two years later was the crime novel that should have made Lewis’s reputation for ever – “GBH”. Written in a frantic, initially perplexing, style the action alternates between the villain hiding in a seaside town and, a year earlier, as king of the porn world in Soho. Is he really hunted, or delusional, or seeking salvation? Read it. It is a brilliantly written fast paced crime thriller, one of the very best written by a British writer, but also, be warned, sleazy, nasty, and violent.

But with that the candle went out. Lewis was 42, but wrecked by his life, his drives, his demons – which his writing perhaps fuelled rather than alleviated. His body was by the time of the publication of GBH poisoned by alcohol, with many essential organs failing to function; in 1982 he died in Scunthorpe Hospital. With his demise both he and GBH were quickly forgotten.

After his death the staff of Barton-on-Humber library took his books from the shelf and threw them into a rubbish skip. It was a detail that Lewis would have enjoyed using in his books.

Further reading:

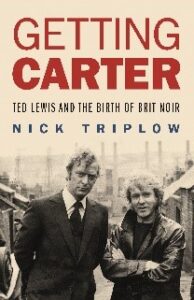

Ted Lewis’s novels are once again available in paperback, Jack’s Return Home and Plender widely so. GBH is out of the 2015 reprint (try Abebooks) but there are rumours of a film. For Lewis’s life and work see “Getting Carter” by Nick Triplow, published in 2017 and still available, hardback only. There is a current Lewis anniversary exhibition at the 20-21 Visual Arts Centre, Scunthorpe, a converted church – another irony Lewis would have enjoyed.