31 May 2018

Stop That! Stop It Right Now!

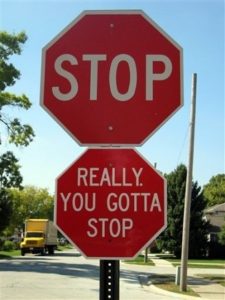

Interfering loses elections.

By J R Thomas

W E Gladstone was very clear what caused the dramatic and unexpected loss of office by the Liberal Party in the 1874 election. Said he: “We have been borne down in a torrent of gin and beer…” That, perhaps not wholly unattractive prospect, was far from the only reason for the voters’ dismissal of his great reforming ministry, but it symbolized the problem. The Liberals had interfered in too many pleasures of the newly enlarged franchise, in particular the pleasures of glass and pot. In the voting booth the well-lubricated had their revenge and chose Mr Disraeli, who knew better than to get between electors and their pleasures.

W E Gladstone was very clear what caused the dramatic and unexpected loss of office by the Liberal Party in the 1874 election. Said he: “We have been borne down in a torrent of gin and beer…” That, perhaps not wholly unattractive prospect, was far from the only reason for the voters’ dismissal of his great reforming ministry, but it symbolized the problem. The Liberals had interfered in too many pleasures of the newly enlarged franchise, in particular the pleasures of glass and pot. In the voting booth the well-lubricated had their revenge and chose Mr Disraeli, who knew better than to get between electors and their pleasures.

Mrs May should learn from that and introduce compulsory history classes for her cabinet. One might expect intervention and control from the Labour Party but at least justified by a coherent reference to a socialist paradise, or at least protection of the weak, where a few rules will increase the happiness of all. There always comes a time when the electorate seems to want a bit of applied discipline and will then vote for a party that will best apply it. At those times there is nothing that parties of a liberal right-orientated persuasion can do to win elections. Indeed, if that mood comes upon the electors in the next three years it will surely propel Mr Corbyn into power. (And out again when the self-same electorate have had enough of being bossed about, and the mood passes.)

But they won’t put up with it from a Conservative (or, in a land far far away, Republican) government. Parties of the moderate right emphasise choice, freedom, lack of government intervention, independence. Their manifestos do not promise that they will seek to make your Mars Bars smaller, or ban smoking in your private motor car, or stop you lighting the wood burning stove in your private house, or indeed interfere with the price of beer. Of course, governments have always legislated to protect the populace from the less desirable effects of unadulterated capitalism, from anti-monopoly legislation to keeping flour pure. But legislating to restrict or ban diesel cars (the use of which the government was not long ago actively promoting) or to make chocolate bars smaller or to ban log burning, moves Nanny State out of the nursery and into every room of the house (and the garage).

All this is always justified by the careful presentation of the most altruistic motives, though one might wonder about the economic benefits to food companies of making choccie bars smaller, and to car makers of hastening the replacement of the nation’s car fleet. The poor are too fat, so we are told, and are ruining the health service by their obesity related illnesses. And old diesel cars, as driven by the poor, are almost as bad as petrol ones. Those who truly care about the planet drive electric vehicles, go to the gym, avoid ice-cream but favour mashed avocado, and use ground source heat pumps.

All this is always justified by the careful presentation of the most altruistic motives, though one might wonder about the economic benefits to food companies of making choccie bars smaller, and to car makers of hastening the replacement of the nation’s car fleet. The poor are too fat, so we are told, and are ruining the health service by their obesity related illnesses. And old diesel cars, as driven by the poor, are almost as bad as petrol ones. Those who truly care about the planet drive electric vehicles, go to the gym, avoid ice-cream but favour mashed avocado, and use ground source heat pumps.

The point of this though is not to present a list of minor grumbles. More it is a warning to the May government, embattled and stressed as it is on every side: remember the voters. Most of them care very little about the powers of the House of Lords, the mechanics of Brexit, the behavior of the Speaker. The man in the street (crossly having failed to get on the Clapham omnibus, it was too full) cares much more about petty little things that affect his daily life.

Not all are petty or little, of course. Most people feel overtaxed and they worry about the availability of care in the NHS. But also they care about potholes and congestion, the cost of beer and the size of Mars bars, about keeping warm in the winter and the price of cheap flights to the sun in the summer, that the bins are emptied before they stink. Life to many electors is a constant financial battle and they want things – food, fuel, parking – to be as cheap as possible. In a battle between price and saving the planet, low price will often win.

There is a pattern here; the lines and scrapings of another battleground between the masses and the elite, the irritating assertion of the tastes of the ruling classes over the grumbling populace. But this battle is economic, even aesthetic, rather than political. The elite recognize they must allow bread and circuses, but still want to specify that the bread must be wholemeal and, please, no performing animals in the circuses.

From the birth of modern British democracy – roughly in 1832 with the passage of the Great Reform Act – the Conservative Party learned the necessity of keeping in touch with what the wider reaches of the electorate wanted from government. It is a policy that, most of the time, has been startling successful, meaning that Conservative governments were the norm for most of the twentieth century. “Set the People Free” was Churchill’s electoral slogan in 1950 (and again in 1951) picking up on the after effects of Atlee’s failure to roll back wartime restrictions fast enough.

Mrs May seemed to have sensed that after her elevation to the Prime Ministership, making many references to the “struggling middles” and her desire to be “an advocate for the ordinary working class family”, suggesting she understands what drives voters outside the Westminster bubble. But words are not actions, and her cabinets’ actions suggest that they know what is good for us – even if many of us do not want to have good enforced on us.

Failure to acknowledge populism can have many manifestations – from the Italian President chucking out a coalition government which 65% of voters supported (albeit in different directions) to English Nature stopping dog walkers on the Norfolk marshes. It is always done for the finest of motives – economically competent national management and preserving nesting birds respectively in these cases – and in suspicion of what we politely call “Populism” but what our more aristocratic and disdainful forefathers called “the Mob”. Call popular will whatever you like, in a democracy the voters are entitled to express opinions, and even have them reflected in the way the country is governed. They may be wrong, they may think the opposite next week, they may be vulgar and badly informed. But a government – and its agencies and local authorities – who did not pay sufficient attention to what the Mob was thinking traditionally got its windows broken, and in this age may, even more painfully, be defenestrated from the pleasures and privileges of high office.

Populism is no new phenomenon but in a democratic age it is dangerous for a government to not pay its full respects to the will of the people. In the USA that has brought to power a President who harnessed that mood, and, whatever might be thought of his hairstyle and lifestyle and Twitterstyle, understands the current popular mood much better than many professional politicians. In the United Kingdom the big issue is all that flows from that Referendum and what happens as we pass through the exit door to what a (modest but angry) majority thought they had voted for.

The disarrayed cabinet would do well to remember that it is not just the big things that can upset the voters. Electors build trust on what they see in those little things that matter so much to them; governments that interfere with simple pleasures will eventually but assuredly pay the price.