25 February 2021

Lies, Damned Lies and Coronavirus

Schools back!

by David Chilvers

On Monday, Boris Johnson announced the return of all pupils to school in England from Monday 8th March. In contrast, two of the three devolved administrations have decided that pupils should return on a staggered basis, with primary schools returning first of all and secondary schools later. Whilst everybody has the re-opening of schools at or near the top of their relaxation wish list, does the strategy in England involve substantially more risk than those being followed by the devolved nations? Given the “cautious return” approach advocated by the Prime Minister, is the strategy in England actually that cautious and free from significant risk?

On Monday, Boris Johnson announced the return of all pupils to school in England from Monday 8th March. In contrast, two of the three devolved administrations have decided that pupils should return on a staggered basis, with primary schools returning first of all and secondary schools later. Whilst everybody has the re-opening of schools at or near the top of their relaxation wish list, does the strategy in England involve substantially more risk than those being followed by the devolved nations? Given the “cautious return” approach advocated by the Prime Minister, is the strategy in England actually that cautious and free from significant risk?

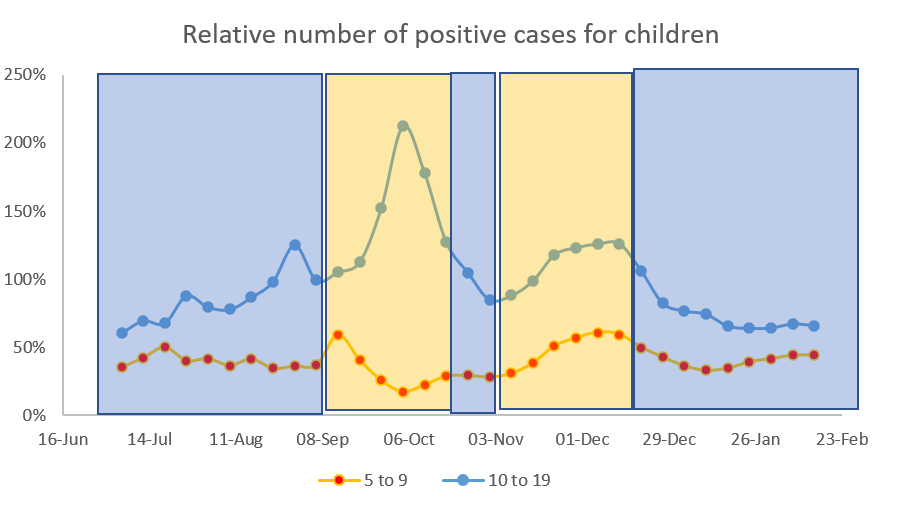

We have noted before that the re-opening of schools in September last year was followed by a significant rise in the number of positive cases among school age children. Since then, we have seen schools closed for the half term break at the end of October and then closed since around 22 December (apart from the one day opening for some at the start of 2021). The chart below shows how the number of positive cases among 5-9 year olds and 10-19 year olds has fluctuated during this period. To aid interpretation, we have taken the positive cases per 100,000 in each age group and indexed them each week against the overall positive cases per 100,000 across all age groups. An index under 100% means that the selected group is less likely than all age groups to have a positive case in that week, an index above 100% means that the selected group is more likely than all age groups to have a positive case that week.

The blue shading on this chart relates to periods when schools were closed – before September, half term and from just before Christmas; the orange shading relates to periods when schools were open.

You can see that for 5-9 year olds – all in primary school – there is modest variation in the number of positive cases per 100,000 relative to the population overall. The rates does go up following the Autumn half term and this might co-incide with the spread of the Kent variant of the virus, believed to be more infectious among children. The rate for this age group is always well under 100%, confirming that young children in this age group appear to be less susceptible to COVID-19.

For the 10-19 age group, the picture is very different. This group is primarily those in secondary school. There is a gentle rise in the relative number of positive cases during the summer, followed by a large rise around two weeks after schools re-opened in September. From mid October through to the Autumn half term, the relative rate fell but when children went back to school in November, the rate rose again to be above 100%. In the two periods that schools were open, the relative rate of positive tests among 10-19 year holds was fairly consistently above average.

This analysis suggests that attending school is correlated with higher relative rates of positive testing among 10-19 year olds but with much lower relative rates among 5-9 year olds. This is consistent with an approach to re-open primary and junior schools first, as is being undertaken in Scotland and Wales – with secondary schools following. But in England, where all schools are to re-open on 8th March, we might expect to see the number of positive tests increase among secondary school pupils, largely due to the mixing at school and the potential this gives for school based infections.

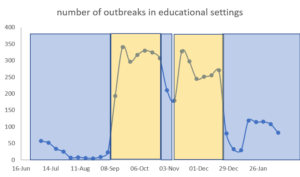

PHE data on the number of outbreaks due to respiratory diseases confirms that this is what happened when schools re-opened in September and again after the end October half term.

The orange boxes are the time periods when educational settings (schools and universities) were opened and you can see that each time re-opening occurred, the number of outbreaks shot up. It is important to emphasise that this data covers all outbreaks due to a respiratory infection, but the vast majority of these are due to COVID-19.

This provides further evidence that a return to all schools might see infections increase among 10-19 year olds especially and in turn they may bring this home to others in their household.

Minutes of a SAGE subgroup – the Children’s Task and Finish Group – confirms this conclusion: “Previous analysis of ONS data discussed at SAGE 65 indicated that children aged 12-16 were playing a higher role in introducing infection into households than those 17 or over (i.e. being the index case). The update of this analysis with data until 2nd Dec [2020] previously discussed at SAGE still supports this, but at a reduced level (medium confidence). The difference remains less marked for those under 12 (medium confidence).” The minutes of the latest meeting of this group conclude that “SPI-M-O’s consensus view is that the opening of primary and secondary schools is likely to increase effective R by a factor of 1.1 to 1.5 (10% to 50%).” For R to stay below 1 given this range of increase, the start point would need to be between 0.65 and 0.9, which is roughly where R is at the moment.

It is worth here looking at the impact of the vaccination programme. As we have seen in previous weeks, this has been progressing well; all those aged 70+ were offered a vaccination ahead of the target date of 15 February and the programme is now extended to those aged 65-69 and later to those aged 60-64. All those aged 50+ will be offered a vaccine by mid April but as we have noted, we think this will be earlier, probably by the end of March, However, there is little crossover between those aged 50+ and the families of school aged children, apart from those instances where grandparents provide some childcare services (taking, picking up from school etc). So, the roll out of the vaccine, excellent though that is, will not reach many households with school aged children until April at the earliest and for some of these households, May or June. There will thus be quite a long period when the effects of secondary school pupils mixing at school will not be counteracted by protection of parents with vaccination.

It is for this reason that the Government is planning to introduce twice weekly testing of all pupils in secondary schools, using Lateral Flow Tests. These will be administered in school for the first two weeks and then at home. Those testing positive will presumably be sent home for self-isolation.

The balancing act for the Government, in allowing all children to return to school in England is whether the resultant increase in the R rate from this activity will be more than balanced by reductions due to the vaccination programme and generally falling levels of infection. The ONS and REACT surveys of last week have R at about 0.8 and below 1 in all English regions, so there is apparently some headroom. This balancing is therefore quite tight to call and doubtless all the modellers have been busy simulating these activities. Let’s hope their models are right this time, as there does not appear to be much of a margin for error.

This article is one of a series; the previous article is here.