17 September 2020

Punctuation, Book Clubs

and the Booker Prize.

By Lynda Goetz

Sadly, Hilary Mantel will miss out on a hat trick in the 2020 Booker Prize to be awarded, rather later than usual this year, in November. She won with both the first and second novels (Wolf Hall and Bring up the Bodies) in her trilogy about Thomas Cromwell, but the third, The Mirror and the Light, has, along with most of the other British contenders, been excluded in the latest cull. This leaves just one Brit, Douglas Stuart, (actually Scottish with dual US nationality who has lived in the States since 2001) in contention for a prize that was, in its original guise, a platform for British and Commonwealth writers. Since it was opened in 2014 to American writers, they have, hardly surprisingly, predominated.

Sadly, Hilary Mantel will miss out on a hat trick in the 2020 Booker Prize to be awarded, rather later than usual this year, in November. She won with both the first and second novels (Wolf Hall and Bring up the Bodies) in her trilogy about Thomas Cromwell, but the third, The Mirror and the Light, has, along with most of the other British contenders, been excluded in the latest cull. This leaves just one Brit, Douglas Stuart, (actually Scottish with dual US nationality who has lived in the States since 2001) in contention for a prize that was, in its original guise, a platform for British and Commonwealth writers. Since it was opened in 2014 to American writers, they have, hardly surprisingly, predominated.

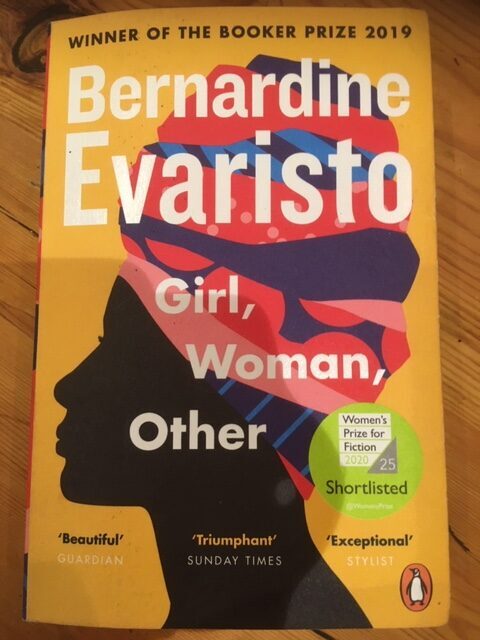

Last year, in a surprising and controversial decision, there were two winners; the relatively unknown British writer, Bernadine Evaristo (of Anglo-Nigerian descent) for her novel Girl, Woman, Other, and the far-better known Canadian, Margaret Atwood, probably best known for The Handmaid’s Tale. Some argued that the inclusion of Margaret Atwood (for The Testaments, her sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale) was mainly to secure more attention for the prize in the States. Whatever the reason, it aroused a great deal of controversy, almost but not quite overshadowing the two books themselves.

Personally, I would not necessarily have chosen to read Ms Evaristo’s book, finding not only the title itself off-putting, but some of the reader reviews distinctly discouraging ( e.g. ‘a collection of twelve loosely linked character studies’; ‘self- indulgent, unreadable and unpunctuated crap’; ‘a love song to modern Britain and black womanhood’). However, one of the good things about being a member of a Book Group is that you are often forced to go along with other people’s choices, which can lead to discoveries that would not otherwise have been made. Although most of the reputable critics were full of praise for this book, that does not always reflect the views of ‘the general reader’. So often the Booker panders to the esoteric and literary in a way which can be excluding and inaccessible to many who enjoy ‘reading’ but do not want to be preached at or ‘learn a new way of looking at the world’.

At first this book was difficult. The characters depicted are not all interesting or likeable. Several are extremely hard to relate to. The lack of punctuation and in particular of full stops is initially disconcerting. The line breaks are strange and make for a completely unfamiliar style. This aspect of the book might however have made it more accessible to current generations of phone and text users, who are, we are told, actually very wary of the full stop. According to several reports and discussions in the national press and on Twitter only a few weeks ago, the full stop in online communication is seen by Generation Z* as passive aggressive, abrupt or quite simply angry. This is partly because many of the young will send a new text for each thought or sentence, so there is not really any need for a full stop. However, it is also a sad truth that English Grammar, including punctuation, is barely taught in schools today where the emphasis has been on ‘self-expression’. If the young manage capital letters for proper nouns and the occasional comma and full stop then they are probably doing quite well.

Bernadine Evaristo, at the age of 61, does not come into this category and her line breaks and lack of full stops are absolutely deliberate and also strangely appealing. After a while the poetic fluidity of her writing takes over and one fails to stumble in any way over her idiosyncratic style. Indeed, it becomes part of the attraction of the book as it becomes increasingly clear too that the way the words appear on the page is at times like poetry and that it in no way hinders reading. This for me did not mean that I could get into the book until over a third or even halfway through when the links between the characters became apparent. By the end when the ‘weaving’ was complete and the historic connections with countries some characters had no inkling they had any connection with had been revealed, I was more than ready to forgive the author for a style and content which at the outset I had felt was didactic, self-absorbed and directed very deliberately at unsettling many of her readers. This was an author who had told her stories with a genuine passion for language, a compassion for her characters and an enchanting twist in the tale. There was humour as well as poetry and in spite of my initial misgivings I ended with an admiration for the writer that I had not expected to feel.

Bernadine Evaristo, at the age of 61, does not come into this category and her line breaks and lack of full stops are absolutely deliberate and also strangely appealing. After a while the poetic fluidity of her writing takes over and one fails to stumble in any way over her idiosyncratic style. Indeed, it becomes part of the attraction of the book as it becomes increasingly clear too that the way the words appear on the page is at times like poetry and that it in no way hinders reading. This for me did not mean that I could get into the book until over a third or even halfway through when the links between the characters became apparent. By the end when the ‘weaving’ was complete and the historic connections with countries some characters had no inkling they had any connection with had been revealed, I was more than ready to forgive the author for a style and content which at the outset I had felt was didactic, self-absorbed and directed very deliberately at unsettling many of her readers. This was an author who had told her stories with a genuine passion for language, a compassion for her characters and an enchanting twist in the tale. There was humour as well as poetry and in spite of my initial misgivings I ended with an admiration for the writer that I had not expected to feel.

Reading this year’s shortlist one can only hope that last year’s ‘cop-out’ double winner trick is not repeated and that amongst all the worthy, woke and bleak topics, humour is not entirely absent. The word ‘funny’ appears in connection with only one of the shortlisted books, so maybe this hope is unlikely to be realised. We could do with both hope and humour in the current climate.

* Generation Z is the name given to the generation born between 1996 and 2015. The previous generation are those known as Millennials.