26 November 2020

KISS and KIV

We need to show as well as tell.

By Richard Pooley

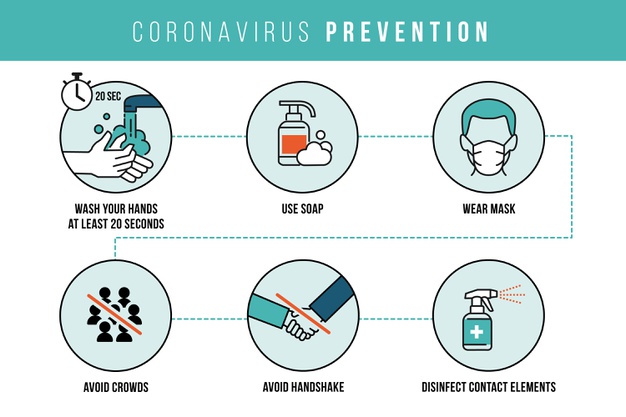

This pandemic has taught us and our rulers many things. One of the most important is the need for government and experts to communicate much more clearly what we should do to reduce the risk of infection. When the next pandemic hits – and it is ‘when’, not ‘if’ – people must be shown as soon as possible, and repeatedly thereafter, what action each of us should take to minimise getting the disease or giving it to others. Note the verb: shown.

“What?“ you are saying. “We were told from the start: ‘Stay at home!’, ‘Keep two metres apart!’, ‘Wash your hands!’ What could be clearer?” You are right. What we were told to do back in March was easily understood by nearly all of us. The messages obeyed the old rule for good communication: KISS – Keep It Short and Simple (the American version prefers ‘Stupid’ to ‘and Simple’ but let’s not go there). But note the verb you and I have just used: told.

For the best thing about those early messages were that they could be seen as well as heard. We were not just told what to do, we were shown what to do. Signs went up everywhere in the UK showing a person inside a house, hands being washed, and people standing two metres apart. In France, where the recommended minimum distance apart is one metre, the 0.65cm baguette was shown as a helpful, if inaccurate, guide to what a metre looked like.

But then the messages changed. They could no longer be shown in pictures. Only in words:

Such entreaties urged us to be good citizens but no longer showed us how to be so. And as the scientists learned more about the virus, the guidance became more complicated and confusing. Should we wear masks? If so, where? Why inside a shop but not inside our houses? How long was it safe to stand talking to someone, even when two metres apart, outside and wearing a mask? And so on. The experts argued with each other on television and radio, in social media and print about how to stop the virus spreading. Words, words, words. Like nearly all of this article, which you have, I hope, no trouble reading.

“Use a picture. It’s worth a thousand words.” So said American newspaper editor, Arthur Brisbane, back in 1911. For much of my career teaching businesspeople communication skills, I trotted out the line that “about 65% of us learn mostly through seeing… Our dominant sense is the visual one.” I must apologise to all my students (some, I know, still read my articles in Shaw Sheet. Hi. Sorry). I learned only two years ago that there is no evidence that this is true. However, this does not mean Brisbane was wrong. Pictures combined with words communicate information far more powerfully than images or words on their own.

This fact is especially relevant if you wish to communicate effectively with a significant proportion of the British adult population: those who can’t read. According to the 2015 OECD Survey of Adult Skills, 16.4% of adults in England have “very poor literacy skills.” The Survey explains what this means. Such people “can read brief texts on familiar topics and locate a single piece of specific information.” They are “functionally illiterate.” 16.4%. That’s one in six adults. Seven million people. A year later the OECD reported that “1 in 4 adults in the UK struggle to read a bus timetable.” How can we expect these people to locate a single piece of specific information among all those new words or new useages of old words cropping up in long articles like this one? A pandemic was not a familiar topic.

“Hang on,” you say, “these people can listen to what is being said on television and radio.” Yes, they can. But how much less persuasive and understandable are messages and arguments when there are no pictures?

On 30 October my son forwarded to us and his sister the English version of a Spanish newspaper article via WhatsApp. – A room, a bar and a class – how the coronavirus is spread through the air..

It was published by El País, the national newspaper with the second highest circulation in Spain (and the highest readership in Spanish online). Have a look at it. Yes, ‘look’. “A room, a bar and a classroom: how the coronavirus is spread through the air” shows, through excellent use of graphics and words, that the risk of catching the virus is highest indoors but can be reduced a great deal by doing certain things.

My son added this message: “Feel like if Gov gave people this info they’d be much more understanding.” Too right, son.

I replied with: “How can we get this out there?”

His answer? “I’m not sure it’s on us to get it out there… I just don’t know why gov ministers don’t go beyond saying ‘the science’.”

You may well have already seen and read the El País article. It went viral. Even so, this fine example of good communication has yet to be matched by anything I have seen in the UK.

Lucy Yardley is professor of health psychology at the Universities of Southampton and Bristol. She attends meetings of the UK government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE). She was interviewed by Justin Webb on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme this Tuesday, warning that families getting together inside for several days over Christmas will result in a build up of levels of the virus which will kill yet more people: “… the worst possible Christmas present is to cause this infection to spread in families.” She said that Webb was “absolutely right” when he opined that we were “concentrating too much on pubs and restaurants and not enough on what we can do in the home.” She had begun the interview by saying that “we need to do more” to stop people “letting their guard down” inside their homes. Webb asked her: “How do we get that across?” She immediately spoke about “our research team” which had produced a website – Germ Defence – “which provides a lot of detailed advice. If you follow that advice, that really reduces infections.”

As soon as the interview was over, I went online and found germdefence.org.

Oh dear. Yes, there is indeed lots of useful advice on the Germ Defence site. But across fourteen densely-packed pages (I think; I did not reach the end) with hardly a picture in sight. What pictures there were added little, if anything, to my understanding. Have a read (yes, ‘read’) and compare with the article in El País.

What a pity. Professor Yardley is a powerful communicator. She was giving good advice. But the website she was promoting does not do the job she wants it to do, even to those like you who are highly literate, let alone the seven million English people who are functionally illiterate. Is that really the best that three British universities – Southampton, Bristol and Bath – could produce?

Keep It Short and Simple, yes. But, just as important, Keep It Visual.

acknowledgement: Tile by <a href=”https://www.freepik.com/vectors/infographic”>Infographic vector created by freepik – www.freepik.com</a>