2 June 2022

Lies, Damned Lies and Coronavirus

Do we spend enough on health?

By David Chilvers

Two weeks ago, we showed that:

- NHS real spending per head has increased substantially over the last 10-15 years

- The number of clinical staff employed has increased by a similar amount

- There is no evidence of any increase in general management positions

- The outcomes investigated – ambulance response times and waiting times in A&E – have deteriorated over the same period, particularly waiting times in A&E, which were on a downward trend well before the pandemic

This appears to suggest that increased funding on its own will not solve NHS problems, as previous increased funding has been accompanied by no improvement in the two areas investigated.

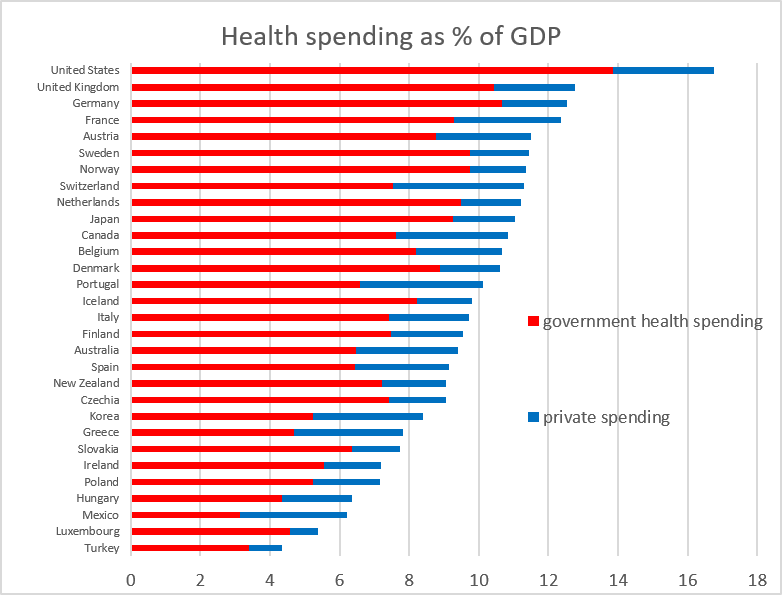

So, is the problem that the UK just does not spend enough on health? We can use some international data from the OECD which provides health spending as a percentage of GDP for a range of countries covering:

- Total health spending

- Government health spending

We have seen from the previous analysis that NHS spending per head has increased in real terms over the past 15 years and is planned to continue to do so. Given the poor outcomes we have seen for waiting times at Accident & Emergency and for the ambulance service, you might conclude this increase is from a very small base and that we are a long way behind other countries. Nothing could be further from the truth, as this OECD data demonstrates:

In terms of total health spending, we are second only to the United States; in terms of Government health spending, we are third, behind the United States and Germany. On both metrics, health spending is at similar levels to the other two large economies in the EU; France and Germany.

There are some countries where private spending on health is more significant than in the UK – Mexico, Hungary, Greece, Korea, Australia, Portugal and Switzerland all have government spending at less than 70% of the total and private spending making up a larger percentage than in other countries. At the other end of the scale, Luxembourg, Slovakia, Czechia, Iceland, Denmark, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Germany, United Kingdom and United States have more than 80% of total health spending financed by the Government. The United States has the largest percentage of total health spending financed by Government, which contrasts with the perceived wisdom that everyone there has medical insurance and the Government ops out.

So, we spend as much on health as most other major economies, more than most, spending and the number of clinical staff has increased substantially in recent years and yet outcomes continue to decline; what is the explanation for this inverse correlation between expenditure and performance? If this happened in a large private company, there would be questions asked about the value of the additional expenditure but it seems that in the UK the response is to just ask for more funding. The more pertinent question would be to ask what return we are getting on what appears to be a level of spending that is high compared to other advanced economies.

We have already seen that performance for waiting times in A&E and for an ambulance had fallen prior to the pandemic in spite of increased resources and spending. So, what about clinical outcomes once you have been admitted into the system? Does the UK have better than average survival rates from major diseases once you have started treatment?

The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine runs the CONCORD programme which collates survival rates from leading forms of cancer in a number of countries around the world. The latest data is here. Out of 58 countries providing information on five year survival rates, the UK ranks:

- 30th for Breast Cancer

- 30th for Prostate Cancer

- 45th for Stomach Cancer

- 49th for Lung Cancer

These results suggest a median position for five year survival from breast and prostate cancer and a bottom quartile position for stomach and lung cancer. There has been a long term screening programme for breast cancer which may have been part of the reason survival from this type of cancer is comparatively better than other forms of cancer and there has been increased awareness in the past few years of the symptoms of prostrate cancer. But these survival rates are not what one would expect from a country where spending and resources are close to the highest among developed nations.

The United States, which has the highest spending on health, has ranks of 2nd, 3rd, 15th and 6th on the four cancers analysed showing some correlation between spending on health generally and cancer outcomes. Turkey, which has much lower health spending than the UK, achieves similar five year survival rates ranking 35th, 33rd, 50th and 48th. Poland, also near the bottom of countries in terms of health spending as a percentage of GDP, has similar outcomes: 45th, 41st, 44th and 31st.

This analysis does not put the UK in a good light. Although second to the United States in terms of health spending as a percentage of GDP, cancer survival rates are much lower. And in spite of spending a lot more on health than either Poland or Turkey, cancer survival rates are similar.

One can only comes to the conclusion that return on investment in health spending in the United Kingdom is poor and there should be greater investigation into how funds are used before more cash is injected into the system. This will run against the prevailing wisdom that the NHS is a National Treasure and can do no wrong but the evidence from data suggests otherwise – it appears to be an organisation that consumes increasing amounts of cash without providing particularly good returns on that investment.

This article is one of a series, the previous article on “NHS spending” is here.