16 April 2020

Demystifying R

The reproduction number.

By John Watson

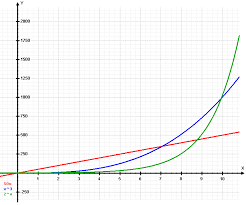

Banged up by the lockdown? Maybe it’s time to get hold of some A-level maths books and try to understand some of the terms being used by the commentators on the progress of Covid 19. Exponential increase? What exactly is that? It sounds big but what does it signify? Never mind, let’s look at the graphs. Oh, the website gives a choice of a linear or logarithmic scale. They’d hardly offer the latter if it wasn’t important, but what does it mean? Are logarithms and exponentials somehow related?

Banged up by the lockdown? Maybe it’s time to get hold of some A-level maths books and try to understand some of the terms being used by the commentators on the progress of Covid 19. Exponential increase? What exactly is that? It sounds big but what does it signify? Never mind, let’s look at the graphs. Oh, the website gives a choice of a linear or logarithmic scale. They’d hardly offer the latter if it wasn’t important, but what does it mean? Are logarithms and exponentials somehow related?

The truth is that only one number really matters, “R”, the reproduction number; that is the number of new cases which on average are infected by an old one. If R is greater than 1, the number of cases must continue to rise as each of those infected gives rise to more than one new case a few days later. If R is less than 1, each generation of the disease is smaller than the one before and the virus will disappear, possibly quite quickly. Suppose R was 1/2, for example, and we take a week as being the period in which new infections occur. Then, after one week the number being infected would be halved; a week later it would be quartered; and after ten weeks it would be below one thousandth of the number you started with.

That sets the common objective for all the countries wrestling with the virus: get R down below 1 from the level of somewhere between 2 and 3 which would be its initial level if no measures were taken; there are a number of different strategies which can be employed to do this.

The first is social distancing. Keep people apart and the virus spreads less easily. Throw in more hand washing and cleaning of handrails etc and R goes down further. If one could isolate people completely, the virus would die out but unless everyone does it everywhere it will spread back once restrictions are removed. That poses a question for island nations which can cut themselves off from the rest of the world. Should they lock down so hard that they rid themselves of the virus on the grounds that they can put all arriving people and goods through quarantine? If a cure or a vaccine emerges quickly that could be a great answer but, if not, the restrictions on imports and travellers could have to stay in place for a very long time indeed as there will be no herd immunity.

The first is social distancing. Keep people apart and the virus spreads less easily. Throw in more hand washing and cleaning of handrails etc and R goes down further. If one could isolate people completely, the virus would die out but unless everyone does it everywhere it will spread back once restrictions are removed. That poses a question for island nations which can cut themselves off from the rest of the world. Should they lock down so hard that they rid themselves of the virus on the grounds that they can put all arriving people and goods through quarantine? If a cure or a vaccine emerges quickly that could be a great answer but, if not, the restrictions on imports and travellers could have to stay in place for a very long time indeed as there will be no herd immunity.

Then there is tracking and trying to chase down and isolate those who are infected. A lot of counties started with that and apps are becoming available to make it more effective. But how effective will it be exactly? It all sounds rather difficult.

A vaccine would be a help too. Even if, like the flu vaccine, it is only partially effective it could help to push that R number down. If the reproduction number without any intervention was 2.5, a vaccine that was 70% effective might reduce it below 1.

You will have heard a lot about herd immunity. If the virus had run unchecked it would probably die out once between 70% and 80% in a community had been infected. That is on the basis that those who have had the disease are unlikely to get it again, at least in the short term. How long would the immunity last? Nobody knows. Catching a cold does not leave you immune forever but the Spanish flu after the first war did die out.

More oblique is the effect of a therapy, a cure or treatment which ensures that fewer of those infected will die or stay ill for long. That would relieve the pressure on hospitals but may not much affect the reproduction number. Also by reassuring the public it may make a tight lockdown politically impracticable.

It is wrong just to regard these as alternatives. One might get R down to 1 by a combination of herd immunity and social distancing. The higher the herd immunity the lower the level of social distancing that would be required. Add in a vaccine and maybe social distancing can be replaced by tracking.

There are difficult decisions to be made and this is where the importance of testing comes in. Not just testing who actually has the disease, important as that is in enabling those people to go into quarantine and for ensuring that lives are saved by treating symptoms early. In terms of ending the epidemic the crucial question is what proportion of the public has had the disease and therefore has some form of immunity against it. That will determine the way in which those policies which will push the R number down should be deployed. Suppose for example that 50% of Britons had been infected. The obvious policy would be to shelter the vulnerable and let the rest of the population push the herd immunity beyond the critical level. Then borders, restaurants and theatres could be opened and a very low level of social distancing would suffice. If, however the herd immunity is much lower (and there have been suggestions that in the UK it is between 5 and 10%), that would probably be a disaster and a far more ferocious lockdown is needed until a vaccine or cure emerges.

The trouble is that no one knows. If you look at the tables, the chances of dying for those who contract the disease are much lower in Germany than in the UK. That could be because their healthcare is superb or their diet contains or encourages antibodies. Much more likely however it is because they test more, pushing the number of cases up and thus the proportion of them resulting in death down. To get policy right one has to test to ascertain what proportion of the population has had the disease. That is why so much effort and money is going into the antibody tests which should be able to provide the answers.