24 December 2015

Shaykh Abdalhaqq Bewley speaks to the Shaw Sheet

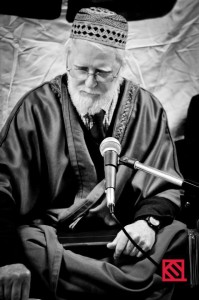

John Watson discusses the development of Europe’s Islamic Communities with Shaykh Abdalhaqq Bewley, Rector of the Muslim Faculty for Advanced Studies

When it comes to understanding the sensitivities of the relationship between the British Muslim community and the host population, Shaykh Abdalhaqq Bewley is in a privileged position. Brought up in the Church of England and educated at Christ’s Hospital, he lived the ordinary life of an Englishman until, after an extensive spiritual search, he converted to Islam in 1968. He was then 22 years old. His religion has taken him on something of an odyssey, first studying in Morocco and then teaching in Nigeria, the US, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Spain, the Caribbean and South Africa as well as in the UK where he is now Rector of The Muslim Faculty for Advanced Studies. He has just moved from Norwich, a city known for its British born converts, to Bradford in Yorkshire where a flourishing Muslim community is served by 140 well-frequented mosques. It was up the M1 to Bradford then that I drove early on a Monday morning to interview him in a substantial Victorian house with a good view over the city.

When it comes to understanding the sensitivities of the relationship between the British Muslim community and the host population, Shaykh Abdalhaqq Bewley is in a privileged position. Brought up in the Church of England and educated at Christ’s Hospital, he lived the ordinary life of an Englishman until, after an extensive spiritual search, he converted to Islam in 1968. He was then 22 years old. His religion has taken him on something of an odyssey, first studying in Morocco and then teaching in Nigeria, the US, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Spain, the Caribbean and South Africa as well as in the UK where he is now Rector of The Muslim Faculty for Advanced Studies. He has just moved from Norwich, a city known for its British born converts, to Bradford in Yorkshire where a flourishing Muslim community is served by 140 well-frequented mosques. It was up the M1 to Bradford then that I drove early on a Monday morning to interview him in a substantial Victorian house with a good view over the city.

Before discussing the issues facing Muslims in Britain, I asked Shaykh Abdalhaqq a more general question about the Islamic approach to mixing with unbelievers. Was it true that a Muslim had a duty to struggle against them? To answer this, it was necessary to start with something more basic: the fundamental focus of Islam on the worship of God. The Shaykh explained that everything in Islam was designed to promote this. For example, Muslims had adopted a simple way of life as bringing them closer to God: essentially the reason which drove early Quakers to adopt a simple style of dress. There was an important difference though. Unlike Christianity, where the injunction to “Render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s” sanctions a separation between the spiritual and secular, Islam permeates everything which its followers do, from their prayers and studies to their business activities. Indeed it was probably the integrity of Muslim traders which enabled the faith to spread during the Middle Ages.

Mohammed, of course, was, among many other things, a warrior and there are verses in the Koran exhorting his followers to attack the enemies of Islam. These had to be read in context, however. In Mohammed’s day, Medina was been under constant attack and had to take an aggressive military line for its own preservation. It did not follow that there was still an ongoing campaign against the infidel and indeed, even in the days of the Prophet, there was considerable coexistence with those of other faiths.

Although, as part of its promotion of the worship of God, Islam has always welcomed converts, it has never had a missionary movement as such and, indeed, the exact way it reached places as far flung as Nigeria and Indonesia is still something of a mystery. Also, there is no tradition of structured spiritual (as opposed to political) authority, something which make a diversion of views within the community hard to check and limits the extent to which one part of the community can influence another.

Shaykh Abdalhaqq pointed out that many of the Muslims in the UK were now third- and even fourth-generation and had pretty much completely lost contact with the countries from which their ancestors had come. England is now their only home. However, when looking at the way in which they interact with the native community it was worth reflecting on what the expectations been when their ancestors had been allowed to settle here, or elsewhere in Europe, in the first place.

Countries like the UK and France already knew a great deal about Islam from their imperial experience and, of course, the expectation was that the new arrivals would practice their religion within the laws of the countries which took them in. At the same time they would, like all immigrant groups, influence the culture they joined and would contribute to it as they were absorbed into the mainstream. For this to be a success it was important that they should understand the host culture and not be separated from it. English Muslims should therefore learn about British history and culture and should be given a thorough understanding of the Christian background which underlies it, even as they study and learn about their own faith. This is important if they are to participate fully in British life and to make progress in the society of which they now form a part. The cross fertilisation will enrich both cultures, the conservative values of Islamic “futuwwa” or “noble qualities of character” – in many ways similar to traditional English values – helping to combat secularism and materialism.

The news that morning had included an item on the recruitment by Siemens of Syrian refugees as apprentices and the value which their work ethic was expected to contribute to the company. In Shaykh Abdalhaqq’s view the contribution which the Muslims could make to wider society went a long way beyond economics, as had the contribution of earlier immigrants, such as the Huguenots and the Jews.

Although there was now a considerable movement of upwardly mobile Muslim families to better neighbourhoods, perhaps reminiscent of the spreading out of the Jewish community from the East End of London, the integration of the Muslim community was likely to take longer both because there were more of them and also because there was, in most cases, a greater difference in appearance. Still, in the end the process was essentially the same.

Moving to the more contentious aspects of integration, I asked what the Shaykh thought drove young people to go and fight for Isil and against the country which they called their home. In most cases he thought that those who went to fight or became radicalised did so because something had gone wrong with their lives. Perhaps they had drifted into drugs and petty crime and Isil presented them with the opportunity of continuing to indulge their proclivities while giving them a kind of religious sanction for doing so. Perhaps they felt unloved and unwanted; maybe there was an unhappy marriage or fractured family relationships. Perhaps they felt frustration at not being able to get jobs or about the living conditions and problems encountered by Muslim communities in Europe – most notoriously in the French banlieues. In most cases, then, the root of the problem was here at home although it was fair to add that the early success of Isil had added a glamour which might in some cases be attractive.

The Shaykh was sceptical, however, at the suggestion that some of them had simply gone out to fight for Isil out of religious conviction. He pointed out that although Isil claims to be Islamic, that was not really the case, since its members are considered by many to fall under the category of being “kharijites”, and respected Islamic scholars had been universal in their condemnation of it. In fact none of the leaders of such terrorist groups seemed to be truly knowledgeable about the religion and their treatment of innocent people was every bit as abhorrent to Islam as it was to western values. Actually the savagery of the movement probably contained the seeds of its own destruction since its claims that those whose views in any way differed from its own could not be Muslims would inevitably lead to more and more schisms and infighting and, if it were to be left to itself, would undoubtedly lead to its self-destruction.

The Shaykh exudes an optimism about the contribution Britain’s Muslim communities could make to our culture and also about the desire of most Muslims to make it. It is a privilege to talk to him and also a relief to listen to someone who looks beyond the present problems and sees an endgame which will enrich everyone.