06 December 2018

Oceania

The Royal Academy

Reviewed by Adam McCormack

Oceania is a vast area of the globe covering, depending on the definition used, as much as one third of the earth’s surface. It extends as far north as Hawaii, south to New Zealand, west to Australia and east to the Pitcairn Islands and beyond. While much of the area is sea (the clue is in the name) there are thousands of islands of widely varying size with diverse populations and cultures. It is then a tough act to try to curate an exhibition celebrating the history, arts and culture of Oceania, but to their great credit, the Royal Academy has done just that. They have put together a great array of artifacts to capture the key elements of the region’s development, thereby telling a story that is impressive and rather sobering.

Oceania is a vast area of the globe covering, depending on the definition used, as much as one third of the earth’s surface. It extends as far north as Hawaii, south to New Zealand, west to Australia and east to the Pitcairn Islands and beyond. While much of the area is sea (the clue is in the name) there are thousands of islands of widely varying size with diverse populations and cultures. It is then a tough act to try to curate an exhibition celebrating the history, arts and culture of Oceania, but to their great credit, the Royal Academy has done just that. They have put together a great array of artifacts to capture the key elements of the region’s development, thereby telling a story that is impressive and rather sobering.

The exhibition has been timed to coincide with the 250th anniversary of Captain James Cook’s scientific expedition to the area, and a number of the pieces are the result of that and subsequent expeditions. Much of the artwork celebrates a life lived on or close to water, with beautifully carved ornamental canoes, paddles and boat decorations. We are given an insight into the ingenuity the islanders used to navigate vast distances in small craft using exquisite wooden grids representing the position of landmasses and currents.

A range of figures, some graphic, others macabre, covers all of life and death and the rituals with which they were celebrated by each of the varied cultures. As we go around some clear themes emerge. The capacity of each area to incorporate the methods and materials of the others is compelling and demonstrates a society looking to develop. This includes a move towards painting and drawing following the visits of European expeditions. There are, however, more chastening messages. The Europeans who brought back some of the artifacts clearly did not always appreciate the significance of them and it does seem, particularly in the case of the Hawaiians, that the area has been left short of items of historical significance making it harder to continue some ancient rituals as intended. The ongoing debate about whether to repatriate some works remains.

A range of figures, some graphic, others macabre, covers all of life and death and the rituals with which they were celebrated by each of the varied cultures. As we go around some clear themes emerge. The capacity of each area to incorporate the methods and materials of the others is compelling and demonstrates a society looking to develop. This includes a move towards painting and drawing following the visits of European expeditions. There are, however, more chastening messages. The Europeans who brought back some of the artifacts clearly did not always appreciate the significance of them and it does seem, particularly in the case of the Hawaiians, that the area has been left short of items of historical significance making it harder to continue some ancient rituals as intended. The ongoing debate about whether to repatriate some works remains.

Other areas of concern relate to what explorers and colonisers brought to the islands. When “travellers” with influenza arrived in Samoa their impact was disasterous, wiping out 22% of the population. In terms of the indigenous culture this was devastating as it was largely the elderly who perished and with them went much of the understanding of the rituals that these exhibits were used  for. Further, while some of the items were obtained through trade, many were taken by force. There is a sad irony in the festive trough towards the end of the exhibition. This was stolen following a bombardment of an island and features carvings of men wielding a number of weapons, including the pistols of the European invaders.

for. Further, while some of the items were obtained through trade, many were taken by force. There is a sad irony in the festive trough towards the end of the exhibition. This was stolen following a bombardment of an island and features carvings of men wielding a number of weapons, including the pistols of the European invaders.

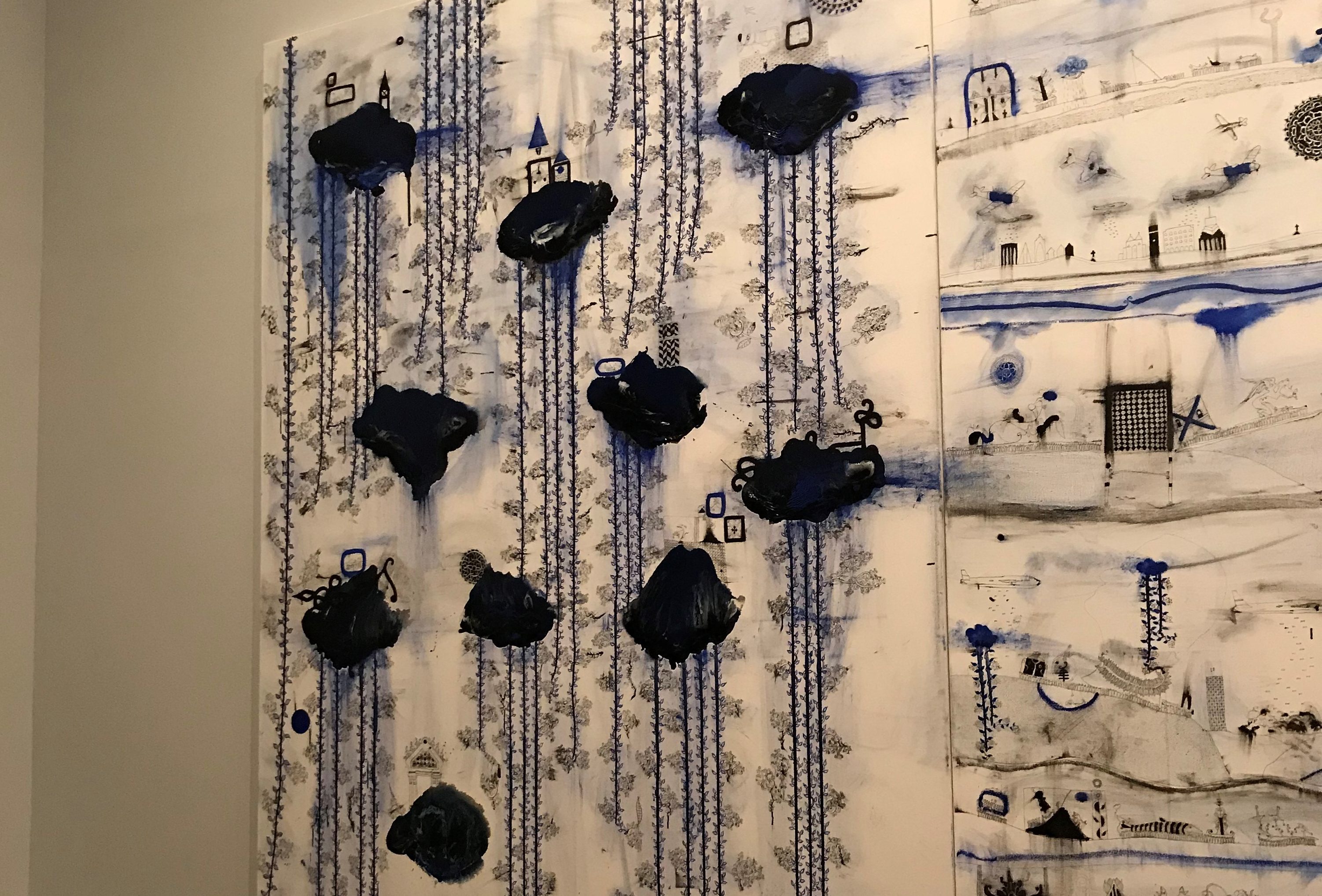

The final gallery has a more modern feel and features a series of panels called To all new arrivals, created by John Pule in 2007. This starts with a series of clouds, covers the development of the islands, the impact of world conflict and eventually a return to the clouds. Sobering indeed.