11 March 2021

Twelve Months On

A lot has changed

by Dan Moondance

An old work colleague recently reminded the Old Farts that it was exactly twelve months since our last get together at the Gardeners Arms in Alderton. He asked what we had all been up to.

I remember that lunch well because it was my turn to organise it, and to my relief we all seemed to have a good time. Two tables of eight, I think it was. But that get together seems so much longer than twelve months ago!

Since then, what have we done? Well, straight after that lunch Trish and I set off for three weeks in Kerala. There were rumours of some nasty flu originating in China but that was mainly confined to people who ate infected bats, not my cup of tea at all. And anyway, surely the Himalayas would protect India from Chinese bugs? We stayed in various Home Stays, a lovely way to travel, and well off the beaten track, but bit by bit the other guests, who were mainly Brits, brought us up to date on the various news bulletins. There were rumours that Boris had forgotten all about Brexit and was trying to persuade everyone to wash their hands while singing Happy Birthday twice. A Shropshire doctor in our midst solemnly warned that there was more to washing hands than just singing Happy Birthday, but did not elaborate. An osteopath from Surrey was adamant that social distancing was nothing new in Virginia Waters. I began to examine my forehead every morning for any traces of a temperature and gave a wide berth to anyone who appeared to be perspiring, a tricky job when the temperature is 30C and there is no air conditioning. By the time we reached our last stop, a luxurious beach resort, the hotel was nearly empty and there were more staff than guests. The staff were under instructions to act as normal but the nice chap who sold us fish from his beach shack was in tears when he told us his worries about what would happen if the tourists stopped coming. Then our travel agent phoned, three days before we were due to go home: the Indian government is going to close the borders next week, so if you don’t get a flight out tonight you will be quarantined. The prospect of endless sunshine and garam masala was almost too good to resist but reluctantly we packed our bags and made for the airport. Everyone except us was wearing masks, and looked as if they were queuing to go into a fallout shelter. Reality struck home. The lady next to me on the plane kept sneezing and wiping her forehead so every ten minutes I did as Boris said and locked myself in the loo, washing hands and singing happy birthday. It did seem to work, because I didn’t catch anything.

By the time we got back there was a daily briefing and very soon the bald, shy looking medical chap who stood next to Boris seemed to be taking on a significant role. It just seemed a pity that all his shirt collars were two sizes too big for him; what was his wife thinking? Soon, every day there were enough statistics being hurled at us to keep half the Civil Service busy preparing them. The news readers who presented them clearly had no idea what they meant and seemed to regard them as some kind of divine utterance. Strangely, when the first lockdown came the weather cheered up and the whole country (or so it felt for those lucky enough to do so) basked in the spring sunshine and wondered if lockdown was such a bad thing after all.

After that, life became a bit of a blur. After years of austerity when we couldn’t even afford to give nurses a pay rise, we now had a chancellor who would even pay us to go out for lunch. Having starved the NHS of money for countless years the government was smitten by guilt and persuaded me to stand on the doorstep every Thursday night, gazing towards the Forest of Dean in the distance, where I clapped hands and attempted to make my old football rattle rotate. As long as I remembered to wear my hearing aid this did bring a sense of community involvement, as I listened to the sheep baa-ing in gratitude on the other side of the hedge.

If nothing else, at least for those of us lucky enough not to have to worry about earning a living, there was the chance to do some of the things that we had always promised ourselves that we would do. In this I failed abysmally. I did not read War and Peace or the complete works of Shakespeare. My boxed DVD set of BBC adaptations of Charles Dickens over the years still sits on the shelf and even now I haven’t managed to get all the way through the Deer Hunter. I did not manage to write any epic poems and the biography of my great grandfather, surely soon to be long-listed for the Booker prize, still hasn’t reached its third chapter. I omitted to buy shares in Amazon, Ocado, or Zoom and didn’t appreciate the potential of Bitcoins until it was too late (correct me if I’m wrong but I thought these were things that jockeys used to persuade their horses to go faster?) Outside, the roses in our garden failed to respond to the extra pruning that they were getting and shed their petals as untidily as they ever did. I did not learn to cook.

There has, at least, been a lot of time for reflection. I think a lot about the old friends who have passed away in the last few years and I wonder if they are smiling at what they have missed. I hope that doesn’t sound too morbid, but my younger brother died just after Christmas, and that does make you think a bit. One thing is certain – we are all twelve months closer to joining them than we were when we met at the Gardeners Arms, and that is quite a warning isn’t it? So it is good to hear from the irrepressible few who have defied the barriers and found ways of carrying on their life almost at the same pace as they always did. Good on you – I envy you your energy and refusal to give in!

Our generation (the one that was born just after the War ended) has been a very fortunate one, hasn’t it? We reaped all the benefits that our parents fought for, and apart from limitless cod liver oil we had the benefit of free education, free health care and a growing economy which provided us with job opportunities and secure pensions at the end of it. And in return, if you were like me, apart from standing to attention on Remembrance Day, we showed little gratitude – our parents were old fogies, stuck in a rut, a week’s holiday in Barmouth was the furthest they would go in their Ford Anglias, and they even criticised the way we dressed and the length of our hair. If only we knew what they had been through! Even though nothing that has happened in the last twelve months can compare with the awfulness of two World Wars, there are frequent comparisons, and at least of them does make me realise how many good things our generation has simply taken for granted.

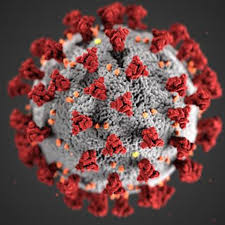

A number of people have told me that this epidemic has confirmed their fears that the planet is doomed and that future generations will pay a heavy price for the way that we have lived. We have, after all, been a very greedy generation. And sadly we cannot escape the conclusion that, far from being the great leveller that everyone thought it would be, this virus and its side effects have landed far more heavily on the poor, the lonely and the dispossessed than they have on the rest of us. Life, and death, are no fairer now than they ever were.

But I see some signs of hope. Social media, which few of our generation understand, is responsible for much damage but has also brought the world closer together in a way that was impossible for our mothers and fathers to contemplate. Public figures such as Donald Trump and Dominic Cummings have used the social media to fan the flames of discontent that inevitably follow when the rich keep getting richer and the poor remain poor. At least we are now rid of both of them, for the time being at least, and although the nationalistic, selfish attitudes that they fostered still remain, there must be hope that as well as publicising those beliefs the social media has made the world sufficiently aware of their existence to avoid another Hitler or another Stalin.

At the other extreme, social media has also fostered the growth of WOKE, and that movement, or way of thinking, is struggling at the moment to draw the line between the necessary fight against prejudice and the misplaced rule of precious dogmatism. It will take a while for this to iron itself out. But in spite of this, the world is, surely, a less blinkered place than it was – you only have to watch the recent brilliant TV series It’s a Sin, concerning the AIDS epidemic, to realise how bigoted we all were, only thirty years ago. The answer to this is not to go around ripping out statues, which will only discredit the movement for proper equality. Instead, it is that each of us should recognise our prejudices, and work to overcome them. And if anything the period of reflection, and gratefulness, that the last twelve months has brought to most of our generation ought to have helped us to do that.