4 February 2021

Lies, Damned Lies and Coronavirus

Comparisons between COVID-19 and Spanish flu

by David Chilvers

This week, we look at how the development of COVID-19 compares to that of the Spanish Flu in 1918-19. This worldwide outbreak comprised three waves, the second of which was the worst in terms of mortality. In the UK, around 228,000 died from Spanish Flu between 1918 and 1919. The population of the UK at that time was 43.5 million, about two thirds of todays’ figure, so in simple terms Spanish Flu would have generated around 335,000 deaths given our current population of 67.9 million people. This is over three times the number that have died so far from COVID-19 in the UK, although the final total is obviously not known as yet.

This week, we look at how the development of COVID-19 compares to that of the Spanish Flu in 1918-19. This worldwide outbreak comprised three waves, the second of which was the worst in terms of mortality. In the UK, around 228,000 died from Spanish Flu between 1918 and 1919. The population of the UK at that time was 43.5 million, about two thirds of todays’ figure, so in simple terms Spanish Flu would have generated around 335,000 deaths given our current population of 67.9 million people. This is over three times the number that have died so far from COVID-19 in the UK, although the final total is obviously not known as yet.

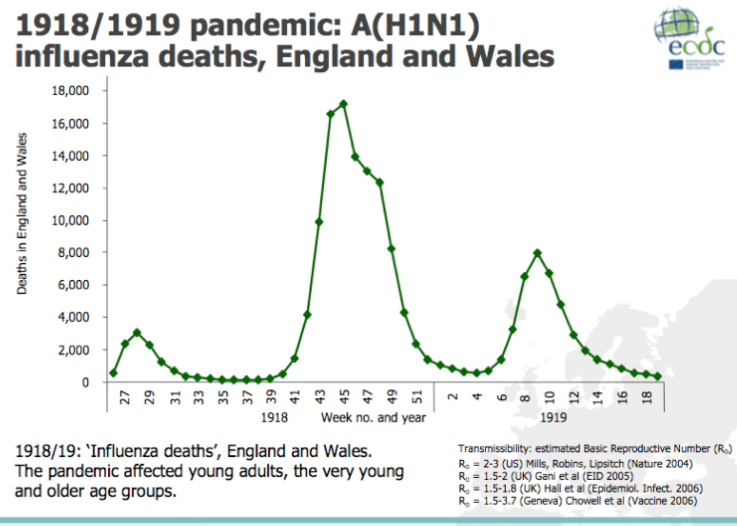

As mentioned, the Spanish Flu outbreak comprised three waves – the chart below shows the mortality data for England and Wales (deaths per week).

As can be seen, the first wave was quite modest but it occurred in the Spring/early Summer of 1918. The second wave was the most severe, peaking in November 2018; this was believed to be at least partly due to celebrations around Armistice Day on 11 November, celebrating the end of the First World War. The third wave was between the first two in terms of size and peaked in February/March 1919.

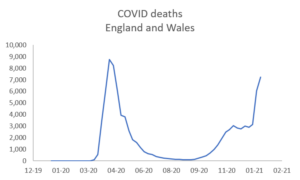

The same chart for COVID-deaths in England and Wales, using the ONS data for weekly death certificates shows this (not totally dissimilar) pattern:

The first wave of COVID-19 peaks in a similar way to the second wave of Spanish Flu; but the peak of the second wave of COVID-19 seems to be larger, relative to the first peak, than that which occurred for the third wave of Spanish Flu.

The Public Health system in 2020 is far more advanced than that in 1918 and we would expect, one hundred years later, that the interventions and mitigations that were put in place in 2020 were far superior to those available in 1918. But it is worth reflecting on commentary at the time of how public health reacted – some comments seem remarkably similar to the current situation.

Hospitals

Hospitals were overwhelmed, and doctors and nurses worked to breaking point, although there was little they could do. Medical schools closed their third- and fourth-year classes and students helped in the wards. There were no treatments against the flu and no antibiotics to treat complications such as pneumonia.

Lock down

In many towns, centres of socialising and entertainment – theatres, dance halls, churches and other public-gathering places were shut, some for months. Streets were sprayed with chemicals and people wore anti-germ masks. Some factories relaxed no-smoking rules believing that cigarettes would help prevent infection.

Hygiene

On 3 November 1918, the News of the World suggested ways to combat the epidemic” “Wash inside nose with soap and water each night and morning; force yourself to sneeze night and morning, then breathe deeply. Do not wear a muffler; take sharp walks regularly and walk home from work.”

Lockdown and hand hygiene seem similar to what we have utilised in 2020/21, whilst the comment on overwhelming hospitals is relevant today; even masks warranted a mention a century ago. There are better treatments available now, via drugs, ventilators and ICU processes more generally, and of course vaccines. This will have helped keep the peak death rate of COVID-19 at little more than half that of Spanish Flu in spite of a population that is 50% larger. Social distancing was not mentioned in 1918 although the closure of the principal places of entertainment and leisure activity in 1918 is paralleled by the closure of the hospitality industry in 2020/21.

For the Spanish Flu, the basic reproduction number of the virus was estimated at between 2 and 3, very similar to that for COVID-19. The close quarters and massive troop movements of World War I hastened the pandemic, and probably both increased transmission and augmented mutation. The war may also have reduced people’s resistance to the virus. Some speculate the soldiers’ immune systems were weakened by poor and irregular rations, as well as the stresses of combat and chemical attacks, increasing their susceptibility. A large factor in the worldwide occurrence of the flu was increased travel. Modern transportation systems made it easier for soldiers, sailors, and civilian travellers to spread the disease.

Another factor was suspected lies and denial by governments, leaving the population ill-prepared to handle the outbreaks. Again, we see parallels with 2020, with widespread travel a way of spreading the virus from country to country and a number of governments, at least initially, being economical with information (or indeed lacking information). And the gatherings at the end of the war and the mass celebrations are not that different from Christmas gatherings in 2020 – both almost certainly contributed to a major increase in transmissions and the development of the next wave.

Natural selection favours a mild strain. Those who get very ill stay home, and those mildly ill continue with their lives, preferentially spreading the mild strain. In the trenches, natural selection was reversed. Soldiers with a mild strain stayed where they were, while the severely ill were sent on crowded trains to crowded field hospitals, spreading the deadlier virus. The second wave began, and the flu quickly spread around the world again.

Although over a century has passed since the Spanish Flu epidemic, there are a lot of parallels with the way to the disease developed (several waves with infections ebbing and flowing). And in spite of the huge improvements in public health in the past 100 years, it is interesting that many of the interventions have been quite similar.

Spanish Flu virtually died out after the third wave, which as we have described was similar to the second wave of COVID. Let’s hope the rapidly reducing cases being seen at the moment and the impact of the vaccination programme also mean that the current wave is the last major outbreak we see. It is, however, worth noting that smaller outbreaks of Spanish Flu continued into 1919 and 1920, with the disease becoming low level but endemic – seems we have heard that story in 2021 as well.

This article is one of a series, find last week’s article “Visiting Care homes” here.