21 June 2018

The importance of imagination – and words

The state of children’s literature, inter alia.

By Lynda Goetz

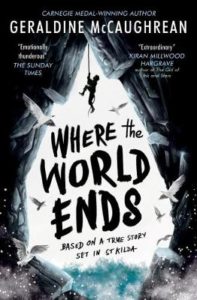

There were eight shortlisted books on the CILIP (Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals) Carnegie Medal Award list. The winner, announced a few days ago, was Geraldine McCaughrean for her novel Where the World Ends. The Carnegie Medal, a major children’s book award which began in 1936, includes amongst its winners the most impressive children’s authors of the last 90-odd years as well as some whose names have been forgotten, as fashions in writing, as well as other things, have changed over the decades.

There were eight shortlisted books on the CILIP (Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals) Carnegie Medal Award list. The winner, announced a few days ago, was Geraldine McCaughrean for her novel Where the World Ends. The Carnegie Medal, a major children’s book award which began in 1936, includes amongst its winners the most impressive children’s authors of the last 90-odd years as well as some whose names have been forgotten, as fashions in writing, as well as other things, have changed over the decades.

In her acceptance speech at the British Library in London, Geraldine McCaughrean, who first won the medal thirty years ago with A Pack of Lies, lashed out at publishers ‘fearful’ of demanding too much of children by using difficult words and ensuring that where books were to go into schools, authors avoided ‘unacceptable’ subjects. Unacceptable subjects are not, as one might have expected in the early days of the award, sexual or political, but things such as witches, demons, alcohol, death or religion. Words considered too challenging for young readers are apparently routinely changed for something simpler. This political correctness and ‘dumbing down’, Ms McCaughrean believes, is limiting and damaging in the long term, a view shared by writer and critic Melanie McDonagh.

For what it’s worth, I would like to add my own condemnation of this approach to children’s literature to theirs. An avid listener to children’s stories when very young and then a reader on my own account, I know that my vocabulary increased massively through the books I devoured. Words which are not much used in everyday conversation pepper the pages of well-written books, both fiction and non-fiction. Words like flamboyant, fragmentation, susurration, cascading, telluric and the example given by Ms McCraughrean, mellifluous, (a wonderfully descriptive word) do not always trip off the tongue in everyday conversation, but they have their place in the written language and our imagination grows with our vocabulary. As this year’s Carnegie medal winner says, “You can only think with the words you’ve got. You can’t think with a diminished vocabulary.”

As for banishing witches, demons, death and religion, where, as Melanie McDonagh asks, would that have left writers like C.S. Lewis, the winner in 1956 (or indeed Philip Pullman, the winner in 1995)? As a reviewer of children’s books, she considers that contemporary authors are writing to current ideology rather than a need to tell a page-turning story. Current ideology results in a plethora of feminist books and means that young adult fiction is the ‘most dispiriting’ of all with stories about being ‘trans, gay, dyslexic or with OCD’. Surely, children want to escape the boring mundanity of everyday life when they retreat into the world of books? They want to lose themselves in a world which is different, not one that is bogged down with the same old stuff they face on a daily basis, one that is full of anxieties about identity, bullying, relationships, disabilities or shopping, but one that takes them far away from all that – even if it is fantastical, unlikely or scary. Such stories may, in fact, say a great deal about the world, but they teach in a subtle ‘unpreachy’ sort of way which is absorbed almost unconsciously by children and young readers, instead of being ‘good’ in a social worker kind of way, which seems to be the case with so much contemporary children’s literature.

Interestingly, historical fiction used to feature more amongst children’s writers and the Carnegie Award winners than it does now (e.g. The Lantern Bearers by Rosemary Sutcliffe 1959; Tulku by Peter Dickenson 1979; Here lies Arthur by Philip Reeve 2008). History can teach us a great deal and it does seem currently to be out of favour at all levels, not just in children’s literature. A past world, just like a future or fantasy world, is far-removed from current life, but feelings of excitement, anticipation sadness, fear, resentment were all there to be experienced just the same, even if the ‘mores’ of the time meant people and situations were dealt with not only very differently but in ways which today would be entirely unacceptable. A good book, written imaginatively and well, enables children to project themselves into different worlds, whether past, present, future or fantastical. New words and new ideas are all part of that adventure.

Geraldine McCaughrean concluded by pointing out that Diary of a Wimpy Kid, by American author Jeff Kinney, is “supposed to be the most popular book with secondary school children now. I’ve got nothing against it, but by the time you’re 15 you should be at ease with reading something on a more advanced level.” Having had a look at what is, effectively, a comic book (with cartoon illustrations between almost every paragraph) I would have to say, I agree. This is more the sort of thing you would expect an eight year-old to be reading. At a time of falling IQs in developed nations, perhaps we should be taking a serious look at possible reasons why. The MEP Daniel Hannan in a Telegraph article proposes his own ‘unscientific theory’ that too much passive TV watching by toddlers may be a cause. What if unimaginative children’s books with limited vocabulary are also contributing to this decline?

Geraldine McCaughrean concluded by pointing out that Diary of a Wimpy Kid, by American author Jeff Kinney, is “supposed to be the most popular book with secondary school children now. I’ve got nothing against it, but by the time you’re 15 you should be at ease with reading something on a more advanced level.” Having had a look at what is, effectively, a comic book (with cartoon illustrations between almost every paragraph) I would have to say, I agree. This is more the sort of thing you would expect an eight year-old to be reading. At a time of falling IQs in developed nations, perhaps we should be taking a serious look at possible reasons why. The MEP Daniel Hannan in a Telegraph article proposes his own ‘unscientific theory’ that too much passive TV watching by toddlers may be a cause. What if unimaginative children’s books with limited vocabulary are also contributing to this decline?