23 July 2020

Telling Tales

Lockdown with Boccaccio.

By Neil Tidmarsh

Once upon a time, there was a king of the Lombards called Agiluf whose queen was very beautiful. She was so beautiful that one of the servants fell in love with her and tricked his way into her bed by impersonating the king in the darkness of her chamber. He’d departed by the time Agiluf joined his wife later that night, but various remarks of hers made the king put two and two together and realise that his place had been temporarily usurped. Without saying anything to her – he was a wise and discreet man and wanted to spare her from embarrassment and shame and upset – he immediately set out to find the culprit.

Once upon a time, there was a king of the Lombards called Agiluf whose queen was very beautiful. She was so beautiful that one of the servants fell in love with her and tricked his way into her bed by impersonating the king in the darkness of her chamber. He’d departed by the time Agiluf joined his wife later that night, but various remarks of hers made the king put two and two together and realise that his place had been temporarily usurped. Without saying anything to her – he was a wise and discreet man and wanted to spare her from embarrassment and shame and upset – he immediately set out to find the culprit.

Realising that only a servant could have found his way to the queen’s chamber and known how to impersonate him, the king went straight to the servants’ dormitory. In the darkness, he made his way from one bed to another, guessing that the culprit would still be awake. The culprit was indeed the only one awake – he pretended to be asleep, but he was betrayed by the rapid beating of his heart, still thumping away from his recent exertions and now thumping all the more with fear. The king didn’t call out his guards or even strike a light – being wise and discreet, he wanted to keep his humiliation secret. He simply took a pair of scissors and, groping in the darkness, cut off the guilty man’s hair on one side of his head so he’d be able to identify him in the morning and punish him on the quiet.

The terrified servant knew that his life was in the balance. But he was no idiot himself. As soon as the king left the dormitory, he leapt out of bed, grabbed another pair of scissors and went round all the other beds in there, giving every one of his fellow servants a haircut just like his own as they slept.

Come the morning, the king had all his household assemble before him. But of course, to his fury and amazement, he found it impossible to identify the guilty individual. Realising that he’d been foiled by an admirably sharp-witted opponent, and that interrogating and torturing every one of his servants to find the guilty one would only publicise a shame which he wanted to keep secret, he simply announced to them all “Whoever it was who did it, he’d better not do it again. And now, be off with you.”

And the servant who did it never did it again, being clever enough not to risk his life for a second time. He was also clever enough not to boast about his adventure to anyone else. So all the other servants never found out what was behind their mysterious haircuts or the king’s enigmatic warning. So everyone – the discreet king, the innocent queen and the ingenious servant – lived happily ever after.

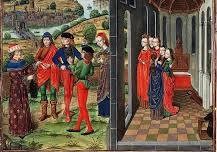

You might recognise the tale – it’s the second story of the third day of Boccaccio’s Decameron. Boccaccio’s set-up is famous enough – the plague descends on Italy in 1348, ten young Florentines flee their pestilence-stricken city and take refuge in a sequence of rural idylls (villa, palace, garden) where they pass the time during lockdown by telling each other stories.

I was reminded of King Agiluf last week, not because I‘m a cuckolded king or a cuckolding servant but because I had a haircut for the first time in six months (“what the hell are those things? Oh, they’re my ears. Right, I remember now. Haven’t seen them for a month or two”) and because Boccaccio and his stories had kept me company throughout the lockdown which lifted as those severed locks fell down onto the barber’s floor.

I take some pride in the fact that I didn’t flee our pestilence-stricken city for the rural refuge ready and waiting for me in Durham (whoops, sorry Mr Cummings, slip of the pen), I mean in Skye (whoops, sorry Mr Gaiman, another slip of the pen), I mean in East Sussex. But I did take refuge with Boccaccio and his ten young Florentines and their stories. This will keep me entertained for the duration, I thought as I took the hefty and hitherto unread Penguin Classic from the bookcase at the end of March, I’ll read one story a day while lockdown lasts. If it worked in 1348, it’ll work in 2020.

And so the stories came, one by one, day by day. Funny stories and tragic stories, bawdy stories and respectable stories, silly stories and serious stories. Stories championing the rights of love and the power of sexual passion. Stories exploring the mysterious workings of Fortune. Stories celebrating that most quick-witted and ingenious of animals, the human being. Morally ambiguous stories, all told by the cheerful, intelligent and sophisticated Boccaccio, a humanist with his tongue more or less permanently in his cheek.

Some were already familiar – the ninth story of the third day was recycled by Shakespeare as All’s Well That End Well, for instance, and Chaucer borrowed the tenth story of the tenth day as the Clerk’s Tale in the Canterbury Tales, and Keats retold the fifth story of the fourth day as The Pot Of Basil. But that’s fine, because Boccaccio himself borrowed from earlier Italian sources and from French sources and from Eastern sources and from classical Greek and Roman sources which themselves no doubt borrowed from even earlier sources, long since lost.

One of Boccaccio’s ancient sources was The Seven Wise Masters, a collection of Eastern tales known in Europe via Greek, Latin and French versions. These stories are told to an emperor by his advisors to try to persuade him of the innocence of his son, who has been sentenced to death for allegedly trying to seduce his step-mother, the emperor’s new wife. Commenting on this collection in his introduction to his Penguin Classics translation of The Decameron, G H McWilliam makes a fascinating point, a point which struck me as incredibly apt every time I closed my copy of Boccaccio for the day and opened the newspaper to find the Covid-19 death toll rising higher and ever higher.

Professor McWilliam points out that in both collections, the purpose of telling stories is to fight against death, to attempt to overcome it. The young Florentines are trying to save their lives from the plague, the emperor’s advisors are trying to save the emperor’s son from execution. “The telling of stories is the means whereby the spectre of imminent death is held at a manageable distance”, he says. He adds that “the classic example of this” is of course The Thousand and One Nights, where Scheherazade preserves her life through her story-telling, cheating death from one day to the next by stopping each night’s story on a cliff-hanger. He says that the idea is also present in Ovid’s Metamorphosis and Apuleius’s Golden Ass (collections of stories which Boccaccio also used). He could have pointed out that the story-tellers in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales are trying to defeat death by winning eternal life in heaven through the penance of pilgrimage.

It’s an intriguing idea, that we tell stories to keep death at bay, that story-telling is a weapon we use in our fight against our most feared enemy, the grim reaper. Could I have been instinctively taking that daily dose of Boccaccio for the same reason that I rationally washed my hands in anti-septic and wore a mask and kept my distance from other people? Does it work? Well, I’m still alive. How does it work? Is story-telling merely a distraction, to take our minds off our inevitable end? Is it an attempt to create an alternative world, an artificial life which the reality of death can’t spoil? Is it an attempt to create something permanent which will live after us and give us some sort of immortality through our art? The Decameron and The Canterbury Tales have given Boccaccio and Chaucer a kind of immortality, after all.

And there was another thing which strengthened my long-held suspicion that all great works of literature have a mysterious but very real magic.

Boccaccio’s young Florentines are ten in number (seven ladies and three men) and their lockdown lasts just ten days (lucky them). They each tell one story a day, so that’s a total of one hundred stories. When I sat down on March 23 – the first day of UK lockdown – to read one story a day, no one had any idea how long lockdown would last. But, as it happened, one hundred stories and one hundred days took me neatly and precisely to July 01 and the lifting of lockdown. If you add in the two weekends when the young Florentines suspended their storytelling (Fridays and Sundays were holy days, and the ladies wanted to wash their hair on Saturdays) that takes us even more neatly to the watershed of July 07, when the pubs re-opened. Job done, Boccaccio, amazing, many thanks. But, Giovanni mate, how did you know?

There’s already talk of another lockdown looming this autumn/winter. But I’m not worried. The Decameron is back on the bookshelf, but beside it I can see another hefty and unread Penguin Classic – Tales From 1001 Nights – ready and waiting. So let’s see: say lockdown starts on October 31 – Halloween, very appropriate. One thousand and one stories – one story a day – one thousand and one days – that will take us to… 28 July 2023. Crikey. Almost three years of lockdown? There won’t be a single toilet roll left in the whole of the world by then.