02 August 2018

Staff College Lecture

Egypt, Pakistan and Zimbabwe.

By Neil Tidmarsh

All right, you horrible lot, pay attention.

All right, you horrible lot, pay attention.

First question: what is our job? Why have our countries given us all these tanks and missiles and firearms to play with?

Yes, sir, you, sir, major of artillery with your hand up. Your job is to help your general to run your country’s oil business and look after its profits, you say? Well, I don’t doubt it, sir, but… Let’s try you, sir, yes, guards major with your hand up over there. Your job is to help your commanding officers to run your country’s construction companies, you say? Yes, yes, but more generally, as well as appropriating the country’s resources and taking over its industries, what is our job? What is it that our fellow citizens – the civilians – expect us brave men and women in uniform to do for them?

Well, I’ll tell you. They expect us to protect them. Yes, they do. But protect them from what, I hear you ask?

The answer to that is simple – to protect them from themselves, of course. Because they can be their own worst enemy, can’t they? I’m sure that’s something we can all agree on, ladies and gentlemen, isn’t it? They don’t understand what’s good for them, do they? They don’t understand order and discipline. Without us, our citizens would descend into a chaotic and corrupt free-for-all; they would become a disorderly rabble of competing mobs.

But ours is not an easy task. The civilians have their own ideas of law and politics, after all, and that’s what makes it so difficult for us. We might know what’s good for them better than they know it themselves, but getting them to swallow the medicine is another thing altogether. So how do we do it? Well, to answer that question we will be looking at three case studies today – the recent elections in Egypt, Pakistan and Zimbabwe.

First, Egypt. In the presidential elections five months ago, Field-Marshal Abdel Fattah al Sisi won a second term with a landslide victory, securing a staggering 97% of the votes. Superb. How did he manage that? Simple – he was the only candidate standing. Oh, wait, no, there was one other – forget his name – some supporter of the Field Marshal – he probably voted for Sisi too. Half a dozen other candidates tried to stand but, well, they all fell by the wayside – some were detained for a variety of misdeeds, some were persuaded to drop out, some were found to be ineligible because their papers weren’t in order, etc, etc.

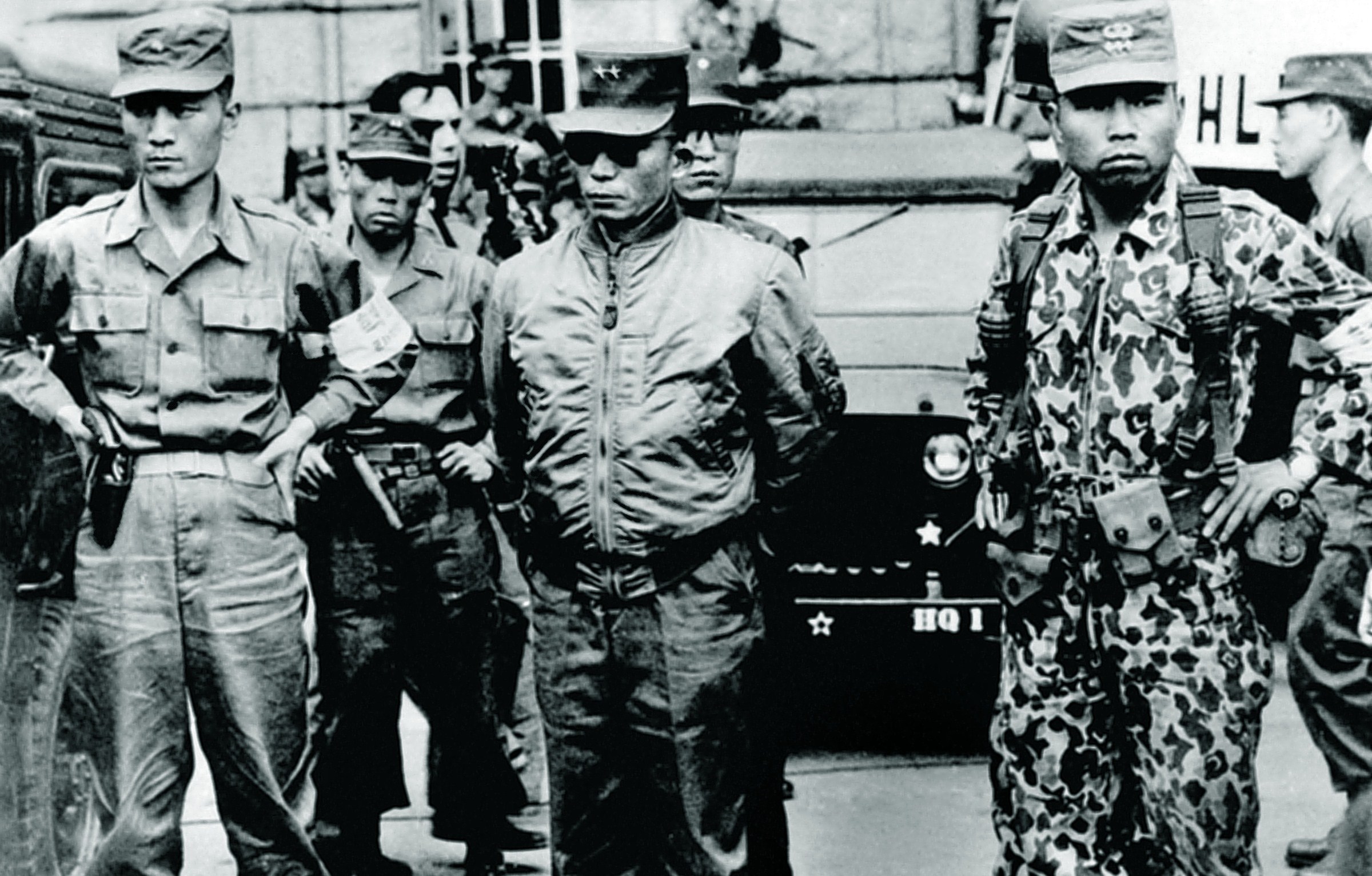

The Field Marshal made it look easy, but of course it wasn’t. You have to consider the work the army had put into consolidating their position over the preceding years. In 2011, the military threw their friend President Mubarak to the wolves when it became obvious that the popular protests against him had become overwhelming and unstoppable and threatened outright revolution. The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces took over. Although elections were organised in 2012, the army stepped in again in the following year when popular protests erupted once more, this time against the Islamist president Mohamed Morsi and his Muslim Brotherhood government. The army, led by General Sisi, removed Morsi from power and again formed an interim government. The Muslim Brotherhood was suppressed. In 2014 Sisi was elected president; coincidentally with 97% of the votes and with only one other candidate (many parties boycotted the election), as in March this year. His first term saw further repression of political opposition, laying the foundations for this March’s exemplary victory.

Second, Pakistan. In spite of a long history of military interference in politics, our brothers-in-arms are playing a rather more subtle game here than they are in Egypt. Since Pakistan’s foundation 71 years ago, the army has launched a number of coups and has enjoyed decades of direct rule; but it had no official candidate in last week’s elections. Nevertheless, all but one of the parties has complained about military interference, claiming that the army has attempted to swing the vote against them by threats and coercion and has manipulated the results by putting obstacles in the way of independent observers and journalists. They allege that the army has covertly backed the only candidate it doesn’t disapprove of – Imran Khan and his PTI party. Ex-president Nawaz Sharif, imprisoned this week for corruption, claims that the army has covertly supported Khan’s PTI to keep his own party – the PMLN – out of office. Sharif was ousted by the military twice in the 1990s, and found himself in conflict with the army – over foreign policy and the defence budget – for most of his most recent term, which ended last year when he was found guilty on charges of bribery and money-laundering which he insists were cooked up by the army and other political opponents.

As it happened, Imran Khan and the PTI did indeed win the election, with 115 seats out of 272; 22 seats short of an outright majority. He is now trying to put a coalition government together – a tricky job as the other two main parties (the PMLN with 64 seats and the PPP with 43) have declared that they are more interested in forming a robust opposition than taking a share in government.

This is a long way from Sisi’s 97% landslide, of course. But perhaps it serves the purpose just as well for the generals who are said to be the real power in Pakistan. A democratically-elected government presenting a respectable civilian face on the world’s stage, but too weak and unstable to challenge them behind the scenes… After all, no democratically-elected prime minister of Pakistan has ever completed his five-year term.

Third, Zimbabwe. For the last three decades, Zimbabwe has been a one-party state governed by Robert Mugabe and his Zanu-PF party. Mugabe relied upon the army to keep him in power, and he shared the fruits of his power with it to ensure its undivided loyalty. Last year the army also decided the thorny question of the 90 year old Mugabe’s succession; in the dust-up between the president’s wife Grace Mugabe and the president’s deputy Emmerson Mnangagwa, it sided with Mnangagwa and eased the president out of office to make way for him. The general who led the move became the vice-president.

It was easy to insist that a new party leader was a party matter, but not so easy to insist that a new president wasn’t a matter for the whole country. Widespread demands for an election were impossible to ignore or resist, and this week the country went to the polls to choose between Emmerson Mnangagwa (leading Zanu-PF) and opposition leader Nelson Chamisa of the MDC party. Nevertheless, there are stories that the army is doing what it can. There have been allegations of intimidation, coercion, delays to prevent people from voting in time (particularly in urban areas, where support for the opposition is concentrated) and delays in publishing results; all, it is claimed, to tilt the playing field in favour of Zanu-PF.

At the moment, the two leaders seem to be running neck-and-neck. How will the army react when the results are finally announced? If Zanu-PF loses, will the military be able to walk away from the power it has shared with the party for thirty years? If Zanu-PF wins, will the military be able to resist consolidating their partner’s power by routing the opposition? As either celebrating victors or angry and protesting losers, are the followers of Nelson Chamisa about to find themselves confronted by troops and tanks?

Remember, ladies and gentlemen, there’s a lot at stake in many parts of the world. Discipline, order, stability – and the profits of a nation’s economy, industries and natural resources which would only tempt our civilians into corruption if left in their hands. There are hard duties and demanding responsibilities which we, the military, must shoulder for their sakes. Thank goodness we have the weapons to do it for them.