28 October 2021

The Making of Rodin

Tate Modern, 18 May – 21 November 2021

Anicka Yi

Tate Modern, 12 October 2021 – 16 January 2022

Reviewed by William Morton

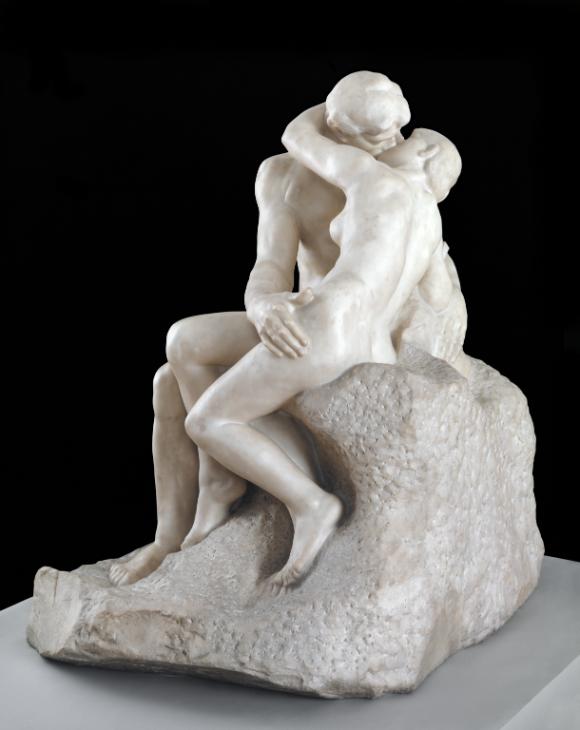

Somewhat late to be reviewing ‘the Making of Rodin’… This is partly due to the pandemic (which has meant that one has failed to see a number of exhibitions including those featuring Andy Warhol, Paula Rego and Artemisia Gentileschi) but also because the exhibition’s focus on Rodin’s works in plaster sounded unexciting. While sculptures such as The Kiss, The Thinker and the Burghers of Calais are powerful and world famous, how much does one need to know about his working methods?

Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) did not achieve success early in his life and worked for a number of years as an assistant in another artist’s studio. His own work gradually gained acceptance (although it was often controversial) in France and, through a friendship with an American curator, in the US. He was firmly established by 1900 and began to receive numerous commissions for busts, to the extent that he employed assistants to make duplicates. While he did marry his long-term companion Rose Beuret in the last year of their lives, like any respectable artist of that era he did not neglect his love life (even attempting, allegedly, to bed Isadora Duncan).

What is clear from the exhibition is the sheer amount of work that Rodin put into his major sculptures. Numerous very detailed studies were made of various parts of the anatomy. Early models of the person or persons portrayed were made to show how they looked unclothed and the effect of various types of clothing. He had a collection of clay models of bits of the body he called ‘the giblets’ as a source of reference and inspiration. All of this before producing something which could be used to cast or carve a final version.

Rodin also often took elements from his sculptures and reproduced them in altered forms or different positions. His Slavic woman head reappears in a number of works. One exhibit is a large- scale version of the head of one of The Burghers of Calais. A hand from the same sculpture is adapted to form a remarkable sculpture in its own right.

An interesting section of the exhibition contains masks of a Japanese actress and dancer, Ohta Hisa, whose expression fascinated Rodin. Although small, they are very striking.

In spite of my initial misgivings, I came away from the exhibition impressed and with a greater understanding of the work and thought Rodin put into his art and of why he has the status of the founder of modern sculpture.

And now for something completely different. Anicka Yi has filled the Turbine Hall with a series of what she calls ‘aerobes’, basically large balloons, many vaguely squid-like with tentacles, which potter around above your head. She has apparently also put together some scents reflecting the odours of Bankside to accompany the exhibit but I could not detect any such ‘odour’. A team of people seemed to be controlling the aerobes, recalling to base occasionally, presumably for a re-boot.

The artist’s idea apparently is to encourage us to think about how machines might inhabit our world (Amazon deliveries by drone?). It is perhaps not the first thought that occurs to one but the exhibit is striking and fun and works well in the space of the Turbine Hall.