08 March 2018

Planning and Infrastructure

New homes and…

By Lynda Goetz

Theresa May’s statement on Monday was welcome. Yes, we do need new homes for the younger generation. Yes, we need them to be affordable and yes, yes, yes, we would love them not to be little identikit rabbit hutches. However…

Theresa May’s statement on Monday was welcome. Yes, we do need new homes for the younger generation. Yes, we need them to be affordable and yes, yes, yes, we would love them not to be little identikit rabbit hutches. However…

However, what we also desperately need is for these homes not simply to be ‘dumped’ in desirable locations where there is neither the infrastructure nor the employment to support them. National Planning Policy (NPP) currently puts Local Plans at the heart of the system and requires that they set out a ‘vision and a framework for future development’. They require regular updating, and should be ‘aspirational but realistic in what they propose’ and ‘tailored to the needs of each area’. A Sustainability Appraisal has to be carried out during the preparation of the Local Plan to attempt to ensure that ‘proposals are the most appropriate given the reasonable alternatives’. All this sounds eminently reasonable and a good democratic way of reaching the ‘relevant environmental, economic and social objectives’. It also sounds relatively simple – which of course it is not.

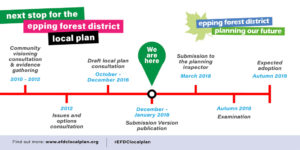

As soon as one thinks about it, it is not difficult to see how quickly the conflicting interests of local authorities, local businesses, local inhabitants, developers and visitors turn a relatively straightforward-sounding task into one which may take years to put together, with endless consultations and discussions on the pros and cons. In February last year the Government published its White Paper Fixing our Broken Housing Market in which it was pointed out that over 40% of local planning authorities had not yet managed to put together a Local Plan, some five years after the launch of the NPP. Last autumn a consultation document (Planning for the Right Homes in the Right Places) was published. This set out, inter alia, the government’s ambition to publish a revised NPP Framework (NPPF) this spring, and highlighted the existence of the £2.3 billion Housing Infrastructure Fund ‘to ensure that essential physical infrastructure, such as schools and roads, is built alongside the new homes we so badly need’. It is this revised NPPF which has just been published as a draft (with supporting documents), with a view to full implementation by the summer. In this way the Government hopes to tackle our current housing crisis in a robust manner. It has been greeted, one might say, with cautious optimism by the planning professionals (Lichfields Blog).

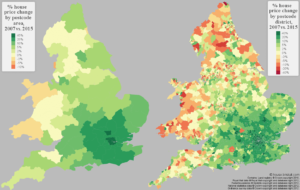

The revised NPPF focuses on housing delivery: on how best to deliver the target of 300,000 homes per annum which it has been calculated are required. Assessing local housing need has hitherto proved arguably too complex and left ‘substantial room for interpretation’. The consultation paper proposed a ‘standard approach’ based on a number of factors which will apparently have the benefit of being much quicker to establish. One of these factors is the affordability of homes – high prices indicating a relative imbalance. Immediately, it is easy to see a problem with this approach (one indeed which would slip very neatly into the ‘Law of Unintended Consequences’). Looking at an affordability map of the UK published with the White Paper, it is clear that places like Devon and Cornwall do not fare too well in the affordability stakes (for fairly obvious reasons). However, an approach which also looks at minimum housing requirements across the whole country (even allowing for a well thought-out Industrial Strategy) is surely going to have difficulty avoiding ending up with excess houses in areas with no jobs, let alone sufficient doctors’ surgeries or schools?

The revised NPPF focuses on housing delivery: on how best to deliver the target of 300,000 homes per annum which it has been calculated are required. Assessing local housing need has hitherto proved arguably too complex and left ‘substantial room for interpretation’. The consultation paper proposed a ‘standard approach’ based on a number of factors which will apparently have the benefit of being much quicker to establish. One of these factors is the affordability of homes – high prices indicating a relative imbalance. Immediately, it is easy to see a problem with this approach (one indeed which would slip very neatly into the ‘Law of Unintended Consequences’). Looking at an affordability map of the UK published with the White Paper, it is clear that places like Devon and Cornwall do not fare too well in the affordability stakes (for fairly obvious reasons). However, an approach which also looks at minimum housing requirements across the whole country (even allowing for a well thought-out Industrial Strategy) is surely going to have difficulty avoiding ending up with excess houses in areas with no jobs, let alone sufficient doctors’ surgeries or schools?

Building more houses would in such instances solve little – except, as has already reputedly happened in some new towns in Devon, to act as housing overflow for the unemployed from more crowded areas. Areas which are largely agricultural are in the future, with the growth of ‘agri-tech’, surely going to require fewer workers rather than more? What are those attracted to the area’s new ‘affordable’ houses going to do by way of employment? One of the main answers to this employment question appears to be ‘tourism’. Does the tourist industry offer that much employment? Does it indeed offer enough to justify turning farming land into tourist playgrounds (e.g. the proposals for J27 M5)?

Leaving aside the employment question, Theresa May’s speech has been met with derision by some, who have claimed that what is needed is ‘building not planning’. However there clearly need to be controls and an emphasis on good design and use of brownfield sites should not be mocked. She says that the ‘new rules will also see to it that the right infrastructure is in place to support such developments… people are worried… their schools are already full, their roads are congested, the waiting list at their GP is already too long. They want to know that any new homes will be accompanied by appropriate new facilities and infrastructure. Under our new planning rules, that’s exactly what will happen. And local communities will be put at the heart of the planning process by seeing to it that all areas have an up-to-date plan’.

Putting in place legislation to ensure that local planning authorities have actually submitted a Local Plan may be a good start. It is worth bearing in mind, though, that the many councils which have so far failed to do so have failed not because of an unwillingness to produce such a plan, but because the process of determining what their area needs in terms of housing and development is not always a straightforward one. Threatening to remove from local authorities the right to decide what their area demands does not however seem like a progressive step. This country needs to build enough affordable homes with the appropriate infrastructure to support the increased population, but we must also be careful to ensure that the penalties and rewards to councils undertaking these tasks do not ignore the realities of the very different areas they are serving. Furthermore, planning is only one aspect of the problem and cannot in isolation solve the crisis. The economy as a whole must also be at the heart of any housebuilding programme as housing without jobs is going to fix little. Having an ‘affordable’ house but being dependant on government handouts (which the country cannot afford either) is no solution.

Putting in place legislation to ensure that local planning authorities have actually submitted a Local Plan may be a good start. It is worth bearing in mind, though, that the many councils which have so far failed to do so have failed not because of an unwillingness to produce such a plan, but because the process of determining what their area needs in terms of housing and development is not always a straightforward one. Threatening to remove from local authorities the right to decide what their area demands does not however seem like a progressive step. This country needs to build enough affordable homes with the appropriate infrastructure to support the increased population, but we must also be careful to ensure that the penalties and rewards to councils undertaking these tasks do not ignore the realities of the very different areas they are serving. Furthermore, planning is only one aspect of the problem and cannot in isolation solve the crisis. The economy as a whole must also be at the heart of any housebuilding programme as housing without jobs is going to fix little. Having an ‘affordable’ house but being dependant on government handouts (which the country cannot afford either) is no solution.