5 April 2018

The Narrowing North-South Divide

House price growth disparity points to a need to cut stamp duty.

by Frank O’Nomics

After decades of house price growth in the south outstripping that north of Watford, the tables are turning. The majority of the UK population is likely to be reassured that the relative wealth across the country is showing signs of finally evening out. However, cries of “you’re not singing any more” may be a little premature, if London is merely a precursor of a broader national move. Further, the factors driving the relative shifts need to be examined, as they may have some additional economic consequences that will be equally uncomfortable in Manchester and London. Falling housing market turnover may be the first stage in a big property correction and addressing this may require a cut in stamp duty.

After decades of house price growth in the south outstripping that north of Watford, the tables are turning. The majority of the UK population is likely to be reassured that the relative wealth across the country is showing signs of finally evening out. However, cries of “you’re not singing any more” may be a little premature, if London is merely a precursor of a broader national move. Further, the factors driving the relative shifts need to be examined, as they may have some additional economic consequences that will be equally uncomfortable in Manchester and London. Falling housing market turnover may be the first stage in a big property correction and addressing this may require a cut in stamp duty.

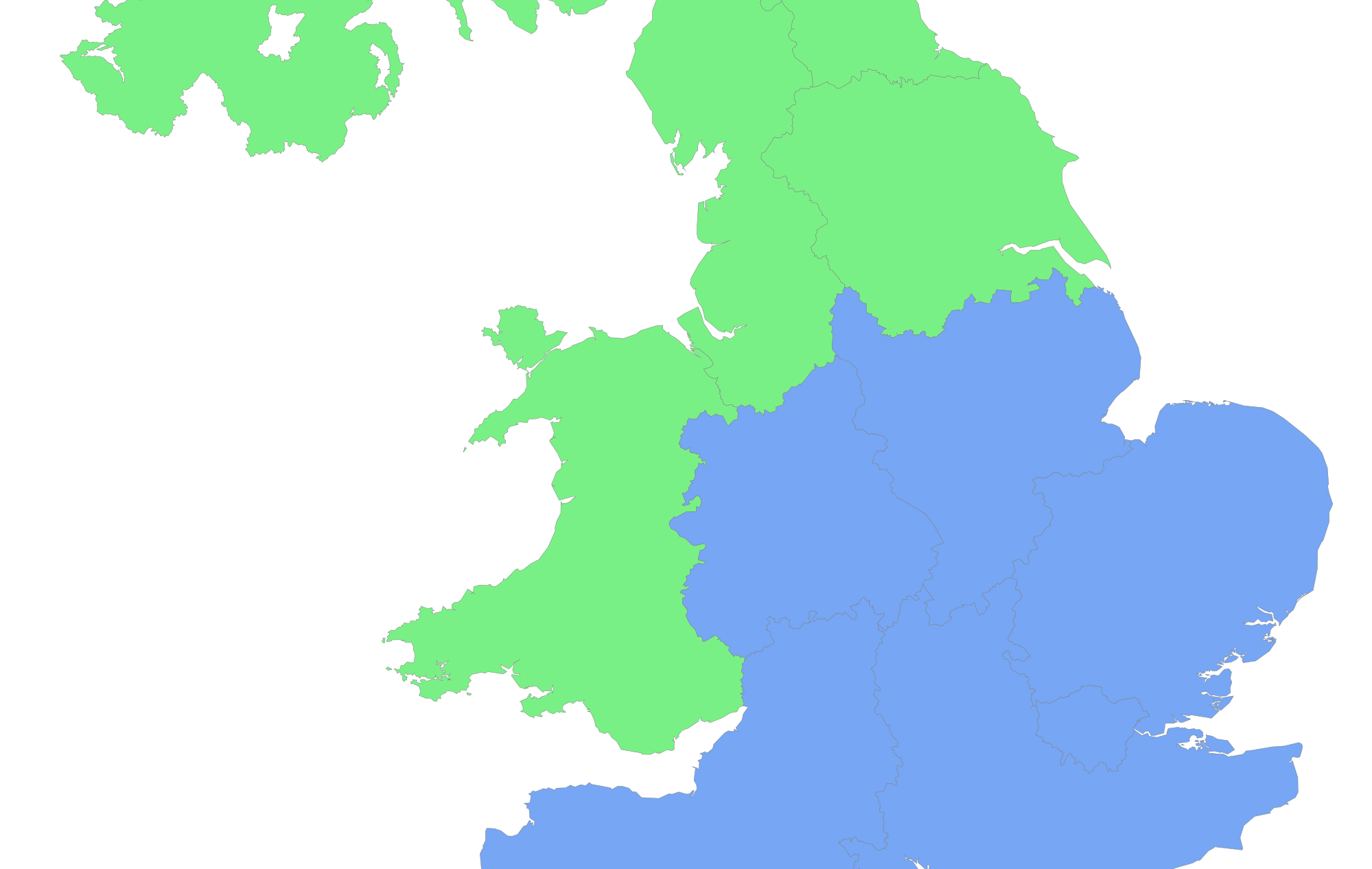

The differences in house price growth have been particularly marked over the last twelve months. London prices are up, overall, a mere 1% (the lowest growth since April 2011), while Edinburgh has seen 8% growth and Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham all over 7%. Areas within London show an even more marked divergence, with two fifths of all post codes showing average prices actually down over the year; the greatest falls being in the City, Camden, Southwark, Islington and Wandsworth. Hometrack now expect overall London house price growth to have turned negative by the middle of the year. To be fair, it is not just London that is suffering, with prices in Aberdeen down 7.7% and those in Cambridge down 1.5%, but Aberdeen is subject to special factors surrounding the oil industry and Cambridge has been behaving like a part of London for some time.

Why isn’t all this good news? There are three reasons. The first that London prices may be regarded as leading the country as a whole. Prices have stalled because of high transaction costs, with increases in stamp duty making it especially difficult for those looking to move to a bigger property to generate the additional cash needed or to justify the move. Tightening lending conditions have also made it much harder for people to access the bigger mortgages needed for a house move. This is only going to get more difficult, with interest rates expected to rise at least twice this year. These factors may apply to a lesser extent outside of London, where fewer properties trigger the higher stamp duty charges, but the effects are being felt.

The second problem is that people are now moving a lot less than they were, regardless of where they live. Homeowners are now moving on average once every 14 years when, prior to the financial crisis, they moved every 9 years. There have been over 6 million fewer property transactions in the last ten years compared to the previous decade. We know that young people are finding it hard to get on the property ladder, and have discussed the reasons why people find it difficult to justify trading up. Added to this is the reluctance of older people to move from the larger properties which have been hit hardest in the correction. Without the incentive of releasing capital on downsizing, many seem to be delaying doing so. Falling turnover is perhaps the first of three stages of a turning property market; the second being a fall in asking prices and the third a reduction in underlying prices. There are economic consequences that ensue from the reluctance of people to move to London, or indeed anywhere, as a lack of geographic mobility inevitably impacts efficiency, but the bigger impact could come from the wealth effects of lower prices – people spend less if they feel poorer. The impact on consumption is highly variable depending on age group, but studies have shown that the house price elasticity of consumption is as high as 1.7 for older homeowners.

There is a final consideration, which is a problem that might actually help prompt the solution. The government is about to appreciate the impact of the Laffer curve, developed in the 1970’s by Arthur Laffer to demonstrate the impact of changing tax rates on the total amount of tax received. Initially, raising stamp duty rates led to an increase in government revenues. However, given the disincentive to move, the fall in the number of property transactions will start to have an impact on the total tax take very quickly. Putting stamp duty up significantly for overseas speculators and buy-to-let landlords has choked off their demand and has placed the reliance to generate property turnover on domestic residential buyers. If this group is also discouraged from looking to sell and buy, the level of turnover dwindles and that is what we are seeing.

Here then lies the potential solution. By reducing the transaction costs for those who are trading their prime residence, by cutting the rate of stamp duty, the property market may start to be rejuvenated and hence so will government revenues. Given that this involves helping those who want to get on to the ladder (currently faced with the reluctance of others to trade up), as well as existing homeowners, it will assist a significant proportion of the UK population – and, more importantly, the electorate. We may have to wait until closer to an election to get any signs of change but the threat to UK household property wealth, which is currently over £4.5 trillion net of mortgages, suggests that a move ought to come a little sooner.