20 June 2019

Natalia Goncharova

Tate Modern (6 June – 8 September 2019).

Reviewed by William Morton

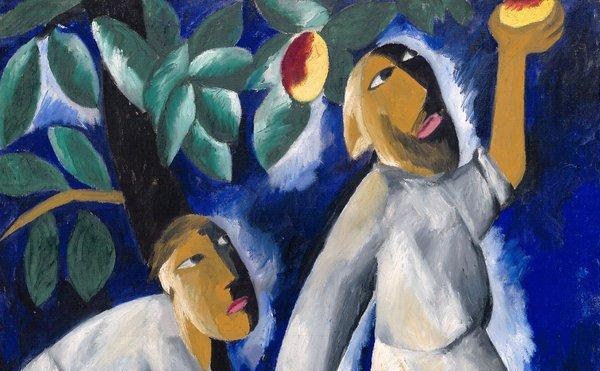

Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962) was born into an aristocratic Russian family which owned a textile business. She was brought up first at their country estate, which she continued to visit after the family moved to Moscow when she was 11. What she saw there clearly made a big impression and many of her early paintings were of country scenes and give an interesting insight into rural life in Russia at that time. In Peasants Picking Apples, the two peasants wear smocks and have primitive faces like African masks. In Picking Apples, the people are painted simply and their attention is not on their job but on a couple canoodling with a background of rolling countryside. There is a photograph of her in the Exhibition wearing peasant dress.

Goncharova studied at the Moscow Institute of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, where she met Mikhail Larionov, who was her partner for the rest of her life. The pair were at the heart of the Russian artistic world and founder members of two avant-garde exhibiting groups, Jack of Diamonds and The Donkey’s Tail. Two wealthy Russians, Morozov and Shchukin, were keen buyers of modern art. Their collections included not only works by Russian artists such as Goncharova and Larionov themselves but many by leading French artists (guess where the Hermitage’s Matisses and Picassos came from?). Their collections were well-known and Goncharova was clearly up to date with developments such as Cubism and Futurism.

The Donkey’s Tail sole exhibition in 1912 included a number of paintings by Goncharova, some of which were her striking re-interpretations of Russian icons and religious paintings. Her four The Evangelists are bleak tall panels, which were apparently removed by the authorities on the grounds that it was blasphemous to include them in an exhibition with a deliberately provocative title.

In the following year, a retrospective of her work (she was only 32) comprising over 800 items was held in Moscow. The Exhibition has a selection of those displayed which are remarkable in the variety of their subjects and of styles. There is Harvest, a nine piece (two lost) with bold colours and simple shapes depicting not cheerful reapers in a cornfield stretching to the horizon but instead apocalyptic images such as Angels Throwing Stones on the City. There is A Smoking Man, clearly influenced by Cezanne. In Jews in a Street, three women, with distinct personalities and one in a long white robe, are shown around a shopfront with a simple display of food.

In 1913 she painted one of her most successful works, the Futurist Cyclist,which captures the concentration of the rider and the movement of his bike on a cobbled road. In the same year, Goncharova and Larionov developed the Futurist-inspired abstract art style of Rayonism, painting objects as an assembly of rays of light.

It is probably fair to say that the years immediately preceding the First World War were the pinnacle of Goncharova’s career. In 1914 she and Larionov started designing stages and costume for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. They were abroad with the Ballets when the Revolution broke out, settled in Paris and never returned to Russia. She remained active, painting and, in particular, designing for ballets and costumiers. There is a charming Russian city backdrop that she designed for The Fire Bird in the Exhibition. However, the old dynamism and spirit seems on the whole to be missing. The result of age or having to leave Russia?

When I went, the Exhibition had very few visitors. It would be a pity if this remains the case as it is very interesting and well worth seeing. I did not, however, gain much impression of Goncharova as a person. With most artists, there is some trait that colours one’s view of their character. They like women or men or the bottle or their garden and possibly too much. Did Goncharova like a laugh? Heaven knows.