18 January 2018

Life is Not a Film

Based on true events

by J.R. Thomas

You are at the movies. All is well with the world. Cinema has become a joyful experience; technology has enhanced film going to an unimaginable level. The deluxe super-seats are better than the home armchair; the wine is potable; the popcorn delicious if annoying; the visual quality is astonishing; modern sound systems are magnificent. Even the adverts are well made entertainments, cinematistic shorts in their own right. Settle down and prepare to enjoy; until…over the opening credits appears the dread words: “Based on True Events”.

You are at the movies. All is well with the world. Cinema has become a joyful experience; technology has enhanced film going to an unimaginable level. The deluxe super-seats are better than the home armchair; the wine is potable; the popcorn delicious if annoying; the visual quality is astonishing; modern sound systems are magnificent. Even the adverts are well made entertainments, cinematistic shorts in their own right. Settle down and prepare to enjoy; until…over the opening credits appears the dread words: “Based on True Events”.

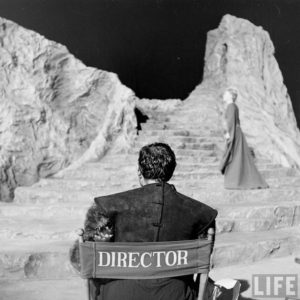

These words, or similar ones, now grace the opening of many a movie. They mean that Hollywood has decided that fiction may enliven truth; that what happened did not have the excitements or ending that the director wanted; or that no writer could be found who could create a good enough story to get the investors target return.

Increasingly what we go to see on the screen is based on true events; the movie houses are becoming lecture theatres on history and politics. Even confining ourselves to the last few months, we have had Churchill; Dunkirk; All The Money in the World; Darkest Hour; and The Post, all serious and expensively made movies dealing with events within living memory. The Post your correspondent has not yet seen but hears is a well-informed, well-balanced examination of the clash between the Washington Post via its editor Ben Bradlee and proprietor Katherine Grahame, and Richard Nixon’s White House. Not so Churchill, which is so much tosh that we will not waste electrical impulses on it; compared to Dunkirk, which uses mostly fictional characters to brilliantly tell the story of one of the most extraordinary military events of all time, like a good play, sketching events through limited resources to reveal an essentially truthful exposition. Mr Churchill currently is revisiting the big screen in Darkest Hour, knocking Churchill into a cocked hat. It has a seminal Winston, via the talents of Gary Oldman. Many actors have attempted the great man but Oldman is perhaps second only to Robert Hardy in his faithfulness to his true character. The film deals with events over a very short period of time, events still well recalled and documented, so that creating a faithful movie is straightforward. And it has no political or social axe to grind, no points to rub into our faces, no agenda to slavishly follow.

None of this can be said of All The Money in the World.

John Paul Getty is said to have said “Any fool can make a fortune. The trick is having a fortune”. He might have added “And to be understood”. The modern world has little affection for billionaires; they are demon kings, ogres, greedmeisters, top of any unpopularity list. It tends to be forgotten that the rich are also human, often complex, with concerns and problem like everybody else. And families.

Mr Getty knew all about the problems of families. He had more than any billionaire prudently should have. Five wives, and five sons, and a large number of grandchildren. He was very careful with money, remembered not for the vast art collection which he built up and the charitable foundation which he endowed with most of his fortune, but for being tight fisted. But Getty (who we will have to denote as JPG1 from now on) is famous for two things – he installed a payphone in his Surrey mansion for the use of guests, and he refused to pay off the kidnappers of his grandson, also John Paul Getty (“JPG3”). These legends we hug with glee at evidence of the sheer nastiness of the rich. Unfortunately neither are more than passing true, but why spoil a good tale?

That seems to be the view of Ridley Scott, one of our greater film makers, whose latest opus this is. Here the legends are centre stage, with further gleeful polishing. The payphone is ludicrously upgraded to a red telephone kiosk sitting in Getty’s hall, and JPG1 hugs his art collection whilst his ex-daughter in law, Gail Getty, tries frantically to raise the ransom money to rescue JPG3 from Italian kidnappers (themselves a bunch of strange gurning peasant types with various scars). The film opens with those dread subtitles “Based on True Events”. Parts of the movie are true enough; JPG3, aged 16, was snatched from the streets of Rome and a series of ransom notes then followed. Most of the Getty family and the Italian police believed that JPG3 might have set this up himself to try to get some money out of grandpa, who was failing to subsidise his family’s Roman life style. JPG3 had publically joked to friends that the only solution was to arrange his own kidnapping. A certain amount of suspicion was not unnatural.

But it was of course a genuine kidnapping, evidenced by the receipt of JPG3’s ear in the post. At this point JPG1 took a more serious interest and began negotiating the ransom down, ultimately from US$17m to S3m, at which point the money was paid and the boy released.

Here we must leave the film behind – other than to remark that the Kevin Spacey version which was completed but withdrawn, was apparently considerably more subtle than the Plummer version in examining the old man’s motives. The real JPG1 wrote an autobiography after those terrible events, pointing out that offering to pay ransom demands on first request just results in bigger and more monstrous demands and, only too often, in the death of the victim. That, and because one successful extortion attempt often results in many more, is why police and governments try to prevent ransoms being paid. The best hope in getting the victim back is usually to keep the kidnappers talking, try to find them, and reduce their expectations. That classic way to resolve a kidnapping, on this occasion, thankfully worked. Gail Getty’s anguish and desperation to get the money and pay it over was heartfelt, but more likely to have produced a tragic outcome. But indeed, let us hope that none of us should ever have to personally explore these choices. Or, if rich, have Ridley Scott make a film about us.

JPG1 died in 1976, three years after the kidnapping. JPG3 suffered a massive stroke in 1982 after a drugs overdose, and was a paraplegic until his death in 2011, aged 54. JPG2, shown in the movie progressively as a drunk, a druggie, and a zombie in a wheelchair, became the great philanthropist Sir Paul Getty, generous hero of so many British good causes. Needless to say, the film makes no reference to that, even in the closing credits. Billionaires bad!

Life is not a movie; humans are much more complex than characters who get one hundred minutes to display their inner and outer lives on the silver screen. But most film viewers watching a film which uses “true events” come blinking back out into the light thinking that what they have seen is more or less true, even subject to the weasel words they barely noticed in the opening credits. In that way, slowly history gets rewritten.

Does that matter? Well, yes, it maybe does. We are entitled not to be traduced after we are dead and gone; if we cannot defend our reputations it matters more, not less, that who we were is not distorted by story tellers trying to earn a few dollars. To descendants and friends there is an obligation to tell something which is, as much as it can be so, the truth. If we are to reach to understand who we are and how humans behave, the complexities of human motivation, of frailty, of greed, the distortions of lust and grief, of trying to make complex judgments as to life and how to live it, we are entitled to see truthful expositions as to human complexity, not have real persons reduced to celluloid stock characters, simplistic goodies and baddies. That might not make for such entertaining movies – but then, life is not a movie.