19 September 2019

It’s the environment, stupid!

United action needed.

By Richard Pooley

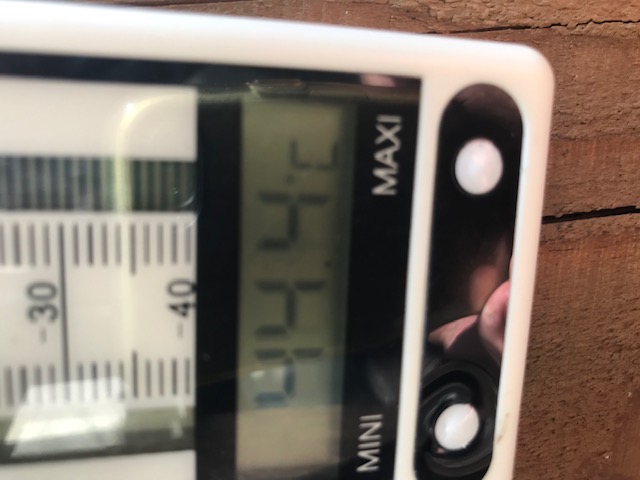

I am writing this in the late afternoon of Tuesday, 17 September in my house in the upper Dordogne valley, south-west France. The thermometer on the vine-shaded balcony reads 38.4°C, 14°C above the norm for this time of year. There is not a cloud in the cerulean blue sky. The window shutters are closed so I can type without my forearms sticking to the table. It’s only 26°C in here. It’s been like this for most of the period since the beginning of June. Maximum daily temperatures have been as much as 16°C above the norm. Friends who were here in late July photographed that thermometer registering 44.4°C in the shade.

If the shutters were open, I would be able to see a garden in various shades of brown, much of it dead or dying. The total amount of rain that has been recorded near here since the beginning of June is 4mm. The average for the four months June-September is a measly 10mm.

I’ll probably go for a swim in the river later. It’s so shallow in the 150-metre wide stretch in front of our village beach, I can walk across. The water reaches no higher than my throat at the deepest point. Normally the authorities release the water from the dams in the mountains of the Auvergne in early September, shortly after La Rentrée, when the French return to work and demand for electricity increases. According to EDF, the release of some of the 225 million cubic metres of water in the Aigle reservoir can raise the level of the Dordogne by four metres within a few minutes. But this summer there has been so little rain in the mountains there have been no releases so far. What this means for electricity supply is not yet clear.

Back in May I wrote an article detailing the climatic and environmental changes that I have seen in this part of France over the last six years – Pas-Normal. I predicted that the growing disquiet of my neighbours would be reflected in the support that the French Green Party (officially known as the European Ecologists and the Greens) received in the European Parliamentary Elections in early June. Sure enough they won 13% of the vote, third behind Le Pen’s National Rally and Macron’s En Marche, but well ahead of the traditional mainstream parties of France, the Republicans and the Socialists.

This disquiet has continued to grow. An abnormally cold Spring has been followed by an unusually hot and dry Summer. Fruit crop yields have been hammered. The biggest local employer, Andros, maker of Bonne Maman jams and much else, is having to import more and more of the fruit that was once supplied from just the Dordogne valley and nearby Limousin. Expect to see the price of those delicious jams go up in your local Waitrose and Sainsburys. Locals are worried that if a proper by-pass is not built to enable Andros’ lorries to avoid the hairpin bends on the main road to the Paris-Toulouse motorway, the company will carry out its oft-repeated threat to move its main factory 45 km north-east to Brive which sits right by the motorway and in the middle of Andros’ new fruit-producing catchment area (Briva was a Romano-Gallic word meaning “bridge”, reflecting Brive’s role as an ancient crossroads).

I was shocked when I received our village’s monthly information sheet for September. Each month those who have been born, got married or died in the previous few weeks are listed. Nearly every month there are more deaths than births. No surprise there. The village has had an old people’s home for decades and the population of around 1300 is kept stable by people moving in from elsewhere. Over the past six years most deaths have occurred in the winter. No surprise there either. But thirteen villagers died in July and August this year, far more than in previous summers, and the nine deaths in August is the highest tally I have seen for any month since we arrived here in 2013. The French Government have announced that 1435 people in France died as a direct result of the two heatwaves the country experienced in June and July. We await their mortality figures for the heatwave we had for most of August and the one we are enduring now.

When on Monday my wife told her 92-year old mother in Gloucestershire of the latest canicule in this region of France, there was little interest even when she converted 38°C to Fahrenheit (100.4°). Apparently it was “very hot” in the Cotswolds too. My parents-in-law and so many of their and my age (late 60s) that I have met in the UK over the past few months are clearly worried about climate change and such things as the amount of plastic in the oceans and the destruction of the Amazon rain forest. But there is nothing like the deep concern that I feel here among French people of the same vintage. For British oldies it’s happening to “them”, out “there”. And, of course, Brexit has pushed all such matters to the margins.

Not so with the younger Brits I have met. My own daughter, a 32-year old advertising executive, has recently returned with her French husband and one-year old twin boys to the UK after eight years living and working in Florida. She and her friends can’t understand us oldies’ obsession with Brexit. Surely, they say as one, what we humans are doing to the planet is far more important and requires our complete attention and urgent action.

In my article in Shaw Sheet last week I repeated the question put to me by a Leaver friend in 2016: “If you were being asked to join the EU rather than leave it, would you join?” My daughter asked me something similar last month: “What are the advantages to the UK of staying in the EU?” I blathered a response until she interrupted with “Yes but what will they do to stop us destroying the planet?” My immediate answer – “Much more than we can do acting on our own” – got her attention. She asked me to explain.

I told her that only by working together with our existing EU partners – negotiating treaties with other countries, pooling resources, collaborating on research and development – could we hope to limit the economic and social damage caused by climate change and environmental degradation. The UK, outside the EU, would have no influence over those many world leaders who deny that the changing climate is a problem or that we humans are destroying our planet. But EU leaders, working together, can at the minimum put pressure on the likes of Trump, Putin and Bolsonaro. Look what happened when the latter tried to deny that his decisions and policies were causing the southern Amazon rain-forest to be destroyed at a faster rate than ever this dry season. The EU, led by President Macron, threatened not to ratify the newly-signed EU-Mercosur free trade agreement if the Brazilian president did not change his tune and do something to stop the fires. Money talks. Bolsonaro blustered, accusing Macron of neo-colonialism and having an old and ugly wife, but in the end had to climb down. Okay, there is not much evidence that sending in the Brazilian army has cut down the amount of illegal burning of the rain forest but South American politicians are now keenly aware that ratification of a treaty of huge economic benefit to their voters will only happen if they pay much more attention to the health of their countries’ environment. Could Boris Johnson and a UK free of the EU (and, soon probably, of Scotland and, later, Northern Ireland) achieve anything similar? The sad thing is that the UK, by leaving the EU, will somewhat diminish the EU’s power to change minds, while at the same time decreasing its own ability to influence. United we stand etc.

There is another reason why staying in the EU can help fight the great fight that the young wish us oldies would wage against climate change and environmental destruction. It’s going to be very expensive to do so. We in the developed world are going to have make enormous sacrifices. We are far more likely to accept doing so if our neighbours are having to make them too and will not take advantage of us. In order for the EU to achieve its zero carbon emission target by 2050 member states will have to be willing to accept much higher electricity prices. Some, the usual suspects Poland and Hungary, plus the Czech Republic, are rejecting this target and its consequences. But they will come round. They will have to. More and more are seeing a greener EU-wide economy as an opportunity to make money. The Latvian prime minister, Krišjānis Kariņš said in June “We have come to the conclusion that this is a hell of an opportunity”.

The Liberal Democrats, the Greens, the Scottish National Party and Plaid Cymru have all hitched their electoral wagon to the Remain cause. It’s a risky strategy. I doubt any one of them will be part of the next UK Government. Britain’s first-past-the-post electoral system will see to that. So too will all those who still want the UK to leave or can’t stomach the notion that the will of the majority of those who voted in 2016 should be ignored. So, the most likely result of the upcoming general election is a government which will take us out of the EU, assuming that we have not already left. But if those four parties can come up with clear and strong reasons why the UK should rejoin the EU, centred around the issue uppermost in the minds of young British voters – Climate Change and the Environment – they have a chance of being part of a British government in the not too distant future.