01 February 2018

“You Value What You Pay For.”

The NHS – what can the Brits learn from the French?

By Richard Pooley

“Nous prendrons notre retraite à la fin de l’année,” Dr Risso told my wife and me with evident glee in October. “Nous” because his wife was my wife’s doctor. Not that my wife had ever met his wife, just a few metres down the corridor in their surgery in our French village. She’s too damn healthy. My wife, that is. But she knew my Dr Risso very well. Frankly, whilst I am often prepared to mutter “d’accord” when trying (but failing) to understand what a French person is saying to me, I have not been willing to lie when I might be being told that I have just a few months to live. So, my bilingual wife has always accompanied me to my sessions with Dr Risso. He was more than happy. It gave him an opportunity to indulge in one of his favourite activities – mocking the English and, in particular, the UK’s National Health Service – knowing that by the time I had grasped the gist of his rapid-fire, nasally-delivered French, he was already on to the next example of the perversity of les anglais. But I was sad to hear of his retirement and glad to know that they were staying put in the village. He was a good doctor and it was largely through him that we came to understand how the French health care system works.

And it works well. Much better than the NHS. Take last month. On the same day that I listened to reports on the BBC of British hospitals with patients waiting in queues of ambulances outside or lying untended on trolleys for hours, I was having to wait in our nearest main hospital, with a bladder full of water, fifteen minutes longer than expected before I could be examined. Uncomfortable, sure. But not life-threatening. Ah, British readers may counter, but the UK had been hit by a double whammy – a flu epidemic and Arctic weather. Oh yes? Well, France has also had far more of cases of flu than usual. And the December-January period was the wettest on record, causing widespread flooding and massive snowfalls. Yet, the results of a blood test done on me at 07.00 one morning by the duty nurse in the village’s infirmerie arrived by post from the test centre across the flooded Dordogne river valley two days later.

Duty nurse? Yes, there are four full-time nurses based in our infirmerie, who when not there travel around the area seeing patients at home or in similar infirmeries in other villages. Want a dentist? The nearest to us is a 2-minute walk down the road. Our village of 1316 people also has two physiotherapists, a podiatrist, an osteopath, an acupuncturist, a speech therapist and a sophrologue (a relaxation therapist, whatever that means).

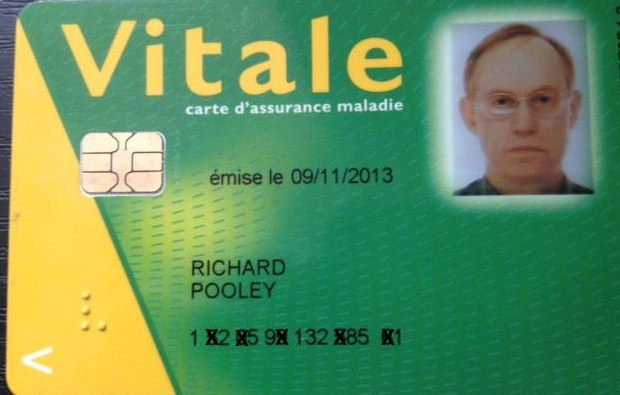

I now give a simple answer to those Brits who ask why I think French health care is so much better than the NHS: “The French pay for it.” When we arrived here nearly five years ago, we assumed that only specialist health care would have to be paid for and that the French State took care of everything else. We were surprised when we discovered that you had to pay every time you went to see your doctor – currently 25€ per appointment. Until last year you had to hand the doctor his fee along with your Carte Vitale – a smartcard which orders the State to put 16.50€ into your bank account within five days. The State also tells your mutuelle to put a further 7.50€ into your account. This was the bigger surprise for us. Nearly all French people have private medical insurance provided by an insurance company – the mutuelle. For most employees the premiums are deducted from their salaries. We are self-employed and have to fork out €113 a month. This is a lot less than we used to pay WPA in the UK; even so we have paid out far more than we have been reimbursed over the last five years. We were told that some services were reimbursed 100%. We have yet to find them. Even that early morning blood test required me to hand over 6.08€ to the bleary-eyed nurse, of which 92% was paid back.

I now give a simple answer to those Brits who ask why I think French health care is so much better than the NHS: “The French pay for it.” When we arrived here nearly five years ago, we assumed that only specialist health care would have to be paid for and that the French State took care of everything else. We were surprised when we discovered that you had to pay every time you went to see your doctor – currently 25€ per appointment. Until last year you had to hand the doctor his fee along with your Carte Vitale – a smartcard which orders the State to put 16.50€ into your bank account within five days. The State also tells your mutuelle to put a further 7.50€ into your account. This was the bigger surprise for us. Nearly all French people have private medical insurance provided by an insurance company – the mutuelle. For most employees the premiums are deducted from their salaries. We are self-employed and have to fork out €113 a month. This is a lot less than we used to pay WPA in the UK; even so we have paid out far more than we have been reimbursed over the last five years. We were told that some services were reimbursed 100%. We have yet to find them. Even that early morning blood test required me to hand over 6.08€ to the bleary-eyed nurse, of which 92% was paid back.

So now we don’t have to pay up front when we see our doctor? Not so. Across France it’s up to each doctor whether they stick with the old system or adopt the new one. Half our village has had to decide over the past four months which of the two remaining doctors they will take on as their médecin traitant. I asked my new French teacher who she had chosen: “Dr Audubert.” “Why?” “Because he is warm and because he demands that you pay him. You must know what things cost. Then you value them. And you do not waste his time.”

There you have it. If only the British could rid themselves of the notion that paying a little up front is not the thin edge of the wedge called privatisation. I well recall my last appointment with my GP before leaving the UK for France. She spent most of the ten minutes allotted to me complaining about the time-wasters who filled up her diary. “Because of them we have to turn people away who are genuinely ill, who then end up clogging up A & E”. When told this story seven months later, Dr Risso focused on the maximum amount of time a UK doctor is supposed to spend with a patient: “Pas plus de dix minutes!! C’est incroyable!”

For all his criticism of the English and the NHS, Dr Risso was willing to bend the rules of his beloved French health care system. He once made out a prescription for new lenses, writing down the lines of letters and numbers from the notes given to her by my wife’s British optician. In France you cannot get new glasses from an optician unless you have first had your eyes checked by an opthalmologist. At that time there was not a single such eye specialist to be found in the Lot Department. When my wife had rung to make an appointment with an ophthalmologist in Brive, 30 minutes away but in a different department, she was told to ring in 6 months’ time when the reservation book would be open for the following year. Dr Risso had no idea what the letters and numbers meant, and made much of the fact that this was the first time in his long career that he had had a patient dictate what he should write down on a prescription. But he chortled as he wrote. Like all true French he knew when it was time to employ Système D* to overcome a problem.

This story illustrates one of the few failings of the French system: the lack of certain medical specialists and, indeed, general practitioners in large parts of rural France. The Rissos have not been replaced, for example. When we told Dr Risso that in the UK it was possible for anyone to walk into Specsavers or the like, have an eye test and buy a pair of glasses on the spot, he snorted in disbelief at this example of “Anglo-Saxon business” trumping the hard-earned expertise of the medical profession. The French government’s solution to this supply problem has been to encourage doctors and specialists from other, poorer parts of the EU to settle in France. Three weeks ago my wife rushed to the infirmerie. There was a piece of Christmas card glitter in one of her eyes and she was in considerable distress; she needed to see an eye specialist immediately. No problem. She got an appointment the next morning with a young Romanian ophthalmologist at a medical centre 20 minutes away. As I waited I saw that his wife, also Romanian, was a doctor in the same centre.

The immigrant doctors and nurses from other EU countries who are leaving the increasingly understaffed NHS because of the Brexit vote (and the abuse and the 15% devaluation of the £ against the € that it triggered) are not necessarily returning home. Many are coming to France where their skills are appreciated and well remunerated. Merci, Boris, Michel, Nigel etc.

*The letter D stands for débrouille or démerde; the verbs se débrouiller and se démerder mean to manage to do and to get out of the shit.