17 December 2020

Excuse Me, Please

Words from the wise.

By J.R. Thomas

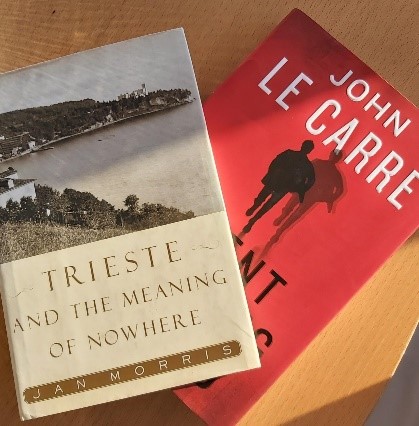

We must not overlook at the closing of this year the passing of two truly great writers. First, John Le Carré, or David Cornwell as he was born and remained in private life. The prints are full of tributes to “a great writer of spy novels” as he must have resigned himself to being thought, but that is like describing Trollope as a historian of the Church of England. Both men were acute and incisive writers about the times in which they lived and the people among whom they lived. As indeed was our second great writer, who died two weeks ago, Jan Morris, not really a travel writer as she was generally described, but a keenly observant ponderer of life who happened to travel.

We must not overlook at the closing of this year the passing of two truly great writers. First, John Le Carré, or David Cornwell as he was born and remained in private life. The prints are full of tributes to “a great writer of spy novels” as he must have resigned himself to being thought, but that is like describing Trollope as a historian of the Church of England. Both men were acute and incisive writers about the times in which they lived and the people among whom they lived. As indeed was our second great writer, who died two weeks ago, Jan Morris, not really a travel writer as she was generally described, but a keenly observant ponderer of life who happened to travel.

Le Carré’s great contribution to literature was in seeing, understanding and delineating over his long life what we tend to think of as “Englishness”. (“Britishness”, properly speaking, but we’ll stick with the common usage.) His greatest character was the civil servant and spy master, George Smiley, a man finding his way through the tricks and treachery not only of his country’s enemies but also of his colleagues and fellow toilers in Whitehall and even of his wife. Smiley knew that those he worked with were sometimes, often, almost as unpleasant as his more deadly opponents in the KGB, but being Englishmen they hid it behind a façade of educated conversation, elegant humour and unfailing courtesy. In that world, jokes and polite wordplay concealed intense dislike, unfailing courtesy masked manipulation, and cups of tea were but cyphers for the flashing rapier that might have been used in earlier society.

Le Carré, the son of a successful confidence trickster and a mother who early abandoned him to his father’s dubious care, knew all about betrayal and untrust; and from that came his understanding of the vital importance of keeping up appearances and of always looking to be in calm control. That, as his many works describe, is the English way. Or was. It really cannot be said to be so now, as the rudeness and vulgarity of public discourse increases. We live in a world which has abandoned the civility of the past, veneer though it might have been, that has lost the ability to create the insult so subtle that the insultee knows not quite how or even whether in truth he has been insulted, or to deploy the veiled barb which may sting the accused but passes unobserved by those around her. Instead, we descend ever further into rudeness and vulgarity; restraint and style melt away and the quality of public exchanges is eroded to trash.

Why should this be? Our previous style may have had an element of hypocrisy, there was falsity in some of our smiles and many witty remarks could be construed on at least two levels, but appearances were kept up and, more importantly, relationships were repairable, because publicly little harm had been done. In 1962 Harold MacMillan, then Conservative Prime Minister, in a vicious and unprecedented manoeuvre, sacked most of his senior ministers in a bid to refresh his party’s electoral appeal; in the Commons the following day, whilst the opposition jeered, the only sign of unhappiness among Tories was a glum silence – and a Conservative backbencher, who rising to quote Kipling, congratulated MacMillan “on keeping his head, while all around him were losing theirs (laughter)”. MacMillan, the unflappable, remained calm and urbane. Consequently, the party did not split, no stilettos were painfully and publicly polished in the newspapers, and life carried on. How party leaders must wish that such splendid restraint were still the thing. Poor Mrs May; the abuse she suffered from her back benches and from her front benches, the scorn, the ridicule. Ms Patel likewise; and as for the stuff that his own colleagues say off and on the record about Boris, one blushes. Maybe he is no good; maybe none of them are or were much good, but the old way of gathering a small number of chaps in grey suits who in a restrained manner would say “Minister, we are terribly sorry to have to say this, but…” seems so much more civilised. And Labour are worse; and as for LibDem remarks about ex leaders, dear oh dear. Oh dear.

But we do not live in times where people are civilised, polite and understanding. Switch on the TV. Two tiny examples. A famous chef hosts what ought to be an exciting programme about young ambitious cooks trying to win a top job. He swears at them like a trooper whose horse has stood on his foot. And they all swear back twice as hard, the women as much as the men. You could never ask your mother to watch this stuff. Nor can nice old ladies tune into comedy shows or game shows. Not only are they full of bad language and very directly vulgar suggestions as to the private lives of cabinet ministers, they are not even funny. A leading comedienne suggesting throwing battery acid over cabinet ministers. The BBC considered this but felt it was “justified in the context”. This is what now constitutes the quality of mass entertainment.

What has happened to our civilised bourgeoise lifestyle – a trifle hypocritical if you like, but at least polite? Why have we lost those attitudes, that style, that sense of humour, which created the English (Scottish, Welsh, Irish) gentleman (and lady)? Our new intemperance and vulgarity, bad temper and public posturing make minor matters so much worse, creates feuds which can never be reconciled, drives wedges so deep that there is no bridging the resultant chasms. Good manners are taken now to suggest weakness: humour is to be avoided as suggesting a lack of certainty: we can no longer be subtle but must sound off, loudly and vulgarly, so that our position is clear.

Jan Morris, in what was effectively her last book, Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere, brooded upon the strange nature of a city which sat at the meeting point of several nations, which was for many decades the Austro-Hungarian empire’s only access to the sea, and what is now an oddly almost detached finger of Italy. The people of Trieste, like the British, and never knowing what might come next, learned to dissemble and conceal, putting up elegant facades to hide whatever might be going on behind. There, she said, “fiction overwhelms fact”. But behind that fiction the city was able to constantly reinvent itself and survive, against many odds and risks.

Maybe we should consider this as an approach for the new normal Britain as it emerges blinking from behind the European curtain, as we nervously open our front doors to receive the literal and metaphorical shot in the arm that will free us, as we consider who and what we must become. We face the world as a small (wet) independent nation, maybe soon as a group of small independent countries, looking for goodwill and opportunities, hoping to buy and sell on good terms, to travel, to advise, to assist and sometimes to be assisted. That might all be much easier if we are once more seen as polite, amusing, subtle, civilised. As people with whom it will be a pleasure to spend time; even if perhaps we are suspected of never being quite what we seem. Maybe we should relearn those lessons from two great writers.