23 June 2022

Ethics and Advice

A brief history.

By Neil Tidmarsh

Well, it could have been worse for Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson. And for Lord Geidt, too. After all, it rarely ends happily for the adviser or the advised where ethics are concerned.

Take that other Alexander, for example; Alexander the Great, who had a better claim to the name ‘Boris’ (meaning ‘glorious warrior’) than our Mr Johnson, and did a good job of achieving Mr Johnson’s as-yet-unrealised childhood ambition of ‘world king’.

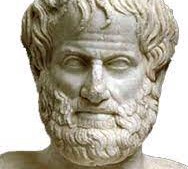

His ethics adviser was none other than Aristotle himself. Alex’s father King Philip II, being the ruler of the up-and-coming power Macedon, secured the services of the top philosopher (ethics is a branch of philosophy, after all – how come Number 10’s adviser was a civil servant and not a professor of philosophy?) as a tutor for his son, to teach him the difference between right and wrong and to keep him on the straight and narrow. And Aristotle stayed on the payroll when Alex became king.

It all went well at first. Aristotle supported and even encouraged Alexander’s invasion of Persia, urging him to be “a leader to the Greeks and a despot to the barbarians, to look after the former as after friends and relatives, and to deal with the latter as with beasts or plants” (which just goes to show how ethics change over time). But then things started to go wrong between them.

Strangely, it wasn’t Alexander’s apocalyptically destructive and murderous rampage through Asia Minor which roused Aristotle’s disapproval, but Alexander’s adoption of Persian ways – his indulgence in luxury and sophistication, his egomaniac’s conviction that he was superhuman and his declaration that he was a god. This was unacceptable decadence in Aristotle’s book, a rejection of Greek simplicity and a blatant contradiction of his humanist beliefs that ‘the middle way’ between two extremes is the wisest course and that ‘man is the measure of all things’. So what did he do? Resign his position and make sure his damning letter of resignation was printed in the national press?

No. He had Alexander killed. At least, according to a rumour widespread at the time. Plutarch quotes a contemporary Greek source called Hagnothemis to claim that Alexander’s death in 323BC was actually a hit job instigated and organised by Aristotle himself; the philosopher procured a deadly poison and persuaded Antipater, one of Alexander’s generals, to administer it.

Our Alexander must have been grateful that his own ethical adviser didn’t resort to such extreme measures.

Fast forward three or four hundred years and we come to the notoriously immoral, the infamously unethical Roman emperor Nero. Believe it or not, he too had an ethics advisor, who, like Aristotle, was also a top philosopher – Seneca, the prophet of Stoicism. And how did that go? Not well, if Nero’s reputation for debauchery, extravagance and tyranny is anything to go by. Someone who had his foster brother poisoned, who murdered his own mother, and his first and second wives, and the woman who refused to be his third wife, and the husband of the woman who did become his third wife, can’t have been listening very carefully to his ethics adviser.

So what did Seneca do? Resign, and make sure that his damning letter of resignation appeared in the national press? No. It seems that Seneca himself lost the ethical plot too. He was implicated in the murder of Nero’s mother, the very woman who had given him the job of tutoring her son in the first place. And he used his position to ruthlessly and no doubt unethically amass staggering wealth. (Becoming one of the richest men in Rome didn’t stop him from preaching the Stoic virtues of poverty, honesty, simplicity and self-restraint, however.)

Nevertheless, his advice must have continued to irritate Nero. The emperor, perhaps anxious to avoid a repeat of the Alexander the Great / Aristotle end-game, eventually had him killed; Seneca was implicated in a conspiracy against Nero and ordered to commit suicide. The philosopher was almost certainly innocent but he had no choice but to cut his wrists and bleed to death (after trying unsuccessfully to poison himself).

Lord Geidt must have been relieved that his boss didn’t resort to such extreme measures to get rid of him and his unwelcome advice.

Soon after that, Nero’s ethical shortcomings caught up with him when his own Praetorian Guards, tired of his debaucheries, rebelled against him and he committed suicide to escape execution. Could there be a lesson for our Boris here?

Next, fast forward a thousand years or so, and we find ourselves in the Middle Ages, when Christian kings had bishops to act as ethical advisers. And how did that work out? Well, it didn’t end happily for Thomas A Becket, did it? Nor for his king, Henry II, who was blamed and ostracised throughout Christendom for Becket’s murder and who was driven to his deathbed by a rebellion of his sons whose upbringing had guaranteed that they wouldn’t recognise ethics or morals if they were poked in the eye with them. It didn’t end happily for Thomas More, either, who was prepared to defend with his life the power and authority of the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church against the ‘heresy’ of Protestantism and a national church of England headed by Henry VIII.

Fast forward another thousand years and we find ourselves in the here and now with a pope who made the headlines this week with his ethical advice and moral judgement about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. His innocent flock in Ukraine, their churches bombed to ruins, lambs facing slaughter by Russian wolves, must have hoped for an outright condemnation of Russia’s “special military operation”, but were bitterly disappointed. Pope Francis could only bring himself to criticise the Russian army’s behaviour in Ukraine, not its actual presence there. His vague accusations put the blame on ‘the arms industry’, not on President Putin.

So where could Boris look for ethical advice these days? Is there a successful contemporary model of the ‘adviser and advised’ partnership which he could follow?

Indeed there is. President Putin and his ethics adviser Kirill, the Patriarch of Moscow and Primate of the Russian Orthodox Church, see eye to eye. During his tenure, Kirill has brought church and state close together. His wealth is alleged to be as much as $4 billion (according to estimates by Forbes) or even more (according to estimates by Novaya Gazeta). He has described Putin as “a miracle of God” and has supported Russia’s intervention in Syria, its annexation of Crimea and its interference in the Donbas. He supports the current “special military operation” in Ukraine (perhaps ethics haven’t changed that much since Aristotle and Alexander the Great, after all) and has blessed Russian soldiers fighting there.

His belief in a traditional, historical Holy Russia greater than Russia’s current political boundaries matches Putin’s “forward to the past” vision of Russia’s historical imperial footprint: no matter that Ukraine is now an internationally recognised independent and sovereign country, the fact that it was once ruled from Moscow in the past apparently justifies Moscow’s present attempts to make sure it’s ruled by Moscow in the future; Russia and Ukraine are bound together by common culture and history; the Ukrainians and Russians are brother Slavs so should all be governed by Moscow.

What ethical advice would he have for Boris? A radical solution to the problem of the Northern Ireland Protocol, perhaps? Would he support a British invasion/annexation of the Irish Republic? After all, Ireland was once part of the British Empire, governed from London for almost a thousand years, no matter that it is now an internationally recognised sovereign and independent country; Ireland and the UK are bound together by common culture and history; the Irish and the English, Scots and Welsh are brother Brits, all inhabitants of the British Isles which could be truly united once again. And it would be the EU’s fault for pushing itself right up against our borders. And the arms industry’s fault, of course. And if the UK’s soldiers could act like perfect gentlemen during such a “special military operation”, it might even escape the pope’s unequivocal condemnation.