28 May 2020

Do It Yourself

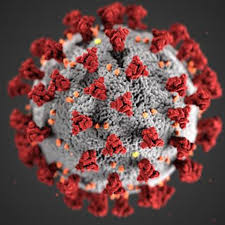

Corona statistics.

By Robert Kilconner

“Blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah… reinfection factor… blah, blah, blah, blah.”

We had a dog once. His name was Patch and he used to lie on the floor during the news and the weather forecast. I don’t know which party he supported. He seemed unmoved by the speeches of politicians. One thing always got his attention though, and that was when the weatherman referred to “patchy fog”. It is possible, of course, that he really cared about the weather and was assessing the prospects for the next day’s walk. Perhaps he was worried about the effect on channel shipping and whether his supply of dog biscuits could be interrupted. But I think not. I think the word “patchy”, of which his name was a part, caused some sort of reflex.

It is the same with “R”, the reinfection factor. We have been told, not least by the Shaw Sheet itself, that the key to driving out the Covid virus is to keep it below 1 which gives all the pundits an excuse for commenting on it. “Somewhere between 0.7 and 1″ says some white-gowned greybeard in a sepulchral tone. “That leaves very little headroom if we are to avoid a second surge. It would be better if it was down near 0.5 and that could be achieved by the Government insisting on… [insert the restriction of choice].”

It is all very impressive, but how do they know what R actually is? Is there some form of R meter, the medical equivalent of a Geiger counter, which can be driven round different neighbourhoods in unmarked vans? Do they go into country districts and ask the locals to lick their fingers and hold them up as they might if measuring the wind? “Ar” someone would say in the Forest of Dean and you would know you were on the right track.

Actually, no, they do not use the R figure to predict the growth of the virus; they start with the figures for the virus (primarily the new cases and death rates) and work backwards to calculate what the R figure must have been. The beauty of this, of course, is that you can do it too.

Sit down in front of your computer and bring up The Times coronavirus tracker by following the link. Then turn to the table headed “Reaching a Plateau” which gives a seven day rolling average for deaths. Look at the latest figure for the UK which, at the time of writing, is that for the 73rd day since the daily average passed five. The tracker shows the average for the previous week at 244. Then go back seven days and look at where that figure was one week earlier: the figure for day 66 is 378. That means that by day 73 the average deaths figure had dropped to about 64% of its level a week earlier. Let’s go back another week: the figure for day 59 was 466 so that over that week the average figure dropped to about 81% of its initial value. Let’s go back another week, 79%. In a table:

| Date | 7 day rolling average of deaths | Decrease over week |

| Day 73 | 244 | 64% |

| Day 66 | 378 | 81% |

| Day 59 | 466 | 79% |

| Day 52 | 589 |

So what does that tell us? Not R itself because one week may not be the average time in which reinfection takes place and there is a time lag, but certainly that in each of the three weeks the death rate dropped and that in the first and third of those weeks the drop was greater than in the week in between.

Information about the past is all very interesting but if you want to make a reputation as a pundit you need to be able to predict the future. Very well, let’s take that figure of 244 and assume that the the weekly death rate continues to drop every week, to 75 % of its previous level; then by day 80 the rolling number of deaths should be 183. By day 87 it should be 137 and by day 101 (four weeks hence) it should be down to 77, a further four weeks taking it to about 25.

Of course all this is a massive simplification and any number of things could blow it off course. The reinfection rate will move up as restrictions are taken off but, against that, will move down if new measures, eg quarantine and tracking, are successful. If it is true, as has been suggested, that in London over 20% have had the virus, then the herd immunity will push reinfection down too. A cure could reduce deaths dramatically. Then there is the fact that the usefulness of death rates as a guide to policy is limited because deaths lag reinfection by between one and two weeks. Why not use the table for new cases further up the tracker? Unfortunately there is no rolling average here and considerable fluctuation. More to the point though, the figure is highly dependent on the techniques of diagnosis and testing, which one hopes improve from day to day, so it is very difficult indeed to make valid comparisons or to draw conclusions from it.