28 October 2021

Culture Wars

Not the way forward.

By Lynda Goetz

In a week when we have had everything from Benin artefacts being sent back to Nigeria; reports of the Royal Opera House (ROH) carrying out a review of classic opera and casting; three museums agreeing that it is time to stop ‘fashionable’ reviews and knee-jerk changes; and the author Lionel Shriver declaring, at a literary festival, that unless we are careful authors will be permitted to do little other than write memoirs, is it perhaps time we took a deep breath and looked rationally at cultural appropriation, diversity quotas and revisionist history?

The Daily Telegraph reported last week that the ROH had pledged to re-examine classic works to make sure future performances accounted for ‘cultural sensitivities’. In fact, this is not breaking news, although the ROH did last week announce a programme to support Black History Month. An executive summary of The Equality, Diversion and Inclusion Strategy actually came out back in May of this year and can be viewed on the ROH website. Miles Chambers, performance poet and playwright, writes about the subject of diversity in opera in an article on the Welsh National Opera website. Crucially in my view, he feels that ‘We need to disassociate its racial past and create opera which reflects the multicultural society we live in…. to maintain a future for opera’. Surely, this amounts to a call for future operas to be more relatable for modern audiences? It does not and should not mean that historic operas should be revised and rewritten to account for current ‘sensitivities’.

Much discussion over the future of opera has focused on the historic inappropriateness of white singers in ethnic roles; in for example, Otello, Aida, or Madame Butterfly. Opera, like theatre, is story-telling. It involves the suspension of disbelief (who in real life goes around singing of their pain or troubles?). It should not really matter if the ethnicity of the actor or singer is appropriate or authentic. In current theatre and film, we are being forced to confront this ‘colour-blindness’ in such productions as the popular Netflix series, ‘Bridgerton’ (where one of the main aristocratic characters was black, at a time in English society where such circles did not contain people of colour) or even the poorly-received production of ‘Anne Boleyn’, where the well-known historical character, second wife of Henry VIII, was played by a black actress.

In the stage adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s ‘The Mirror and the Light’, (about the rise and fall of Thomas Cromwell) currently on at the Gielgud theatre in the West End until the end of November*, three of ‘Cromwell’s boys’, (his son, his nephew and his protégé, Rafe Sadler) were played by black actors. The other two, Richard Riche and Wriothesly, who incidentally both betrayed him, were played by white actors. Clearly, none of Cromwell’s relatives were black. Should they have been played by black actors? What might have been the reaction had the two traitors been played by black actors? These questions matter, because, as things stand, we risk creating a different sort of two-tier system. This is hypocrisy of the highest order. Either it is okay for people of different ethnicity to portray characters not of the same ethnicity, or it is not. In the future we can create plays and operas which contain appropriate proportions of ethnic characters, but in looking at historic productions, perhaps set in an identifiable era of history, ours or that of another country, should it be important that the characters are ‘correctly’ cast or are we prepared to suspend disbelief in any direction?

Earlier this week three leading museums signalled their approval of what The Telegraph dubbed an ‘anti-woke’ charter in a bid to protect Britain’s heritage from activists and ‘temporary shifts in public sentiment’. The Victoria and Albert, The Museum of Home and the Science Museum all lent their support to a report entitled History Matters written by Trevor Phillips, the writer and broadcaster, for the Policy Exchange think tank. The report argues that the ‘growing trend to alter public history and heritage without due process’ should be replaced by ‘a set of key overarching principles applicable to any institution and to any context by which proposals to re- interpret our history should be assessed.’ The government are said to be examining it closely.

At the Cliveden Literary Festival, author and journalist Lionel Shriver expressed again the concerns she has voiced repeatedly over the last few years regarding ‘politically correct’ views and cultural appropriation. In an article in the Guardian in February 2018, she reiterated her hopes, first expressed at the Brisbane Literary Festival in 2016, that the concept of ‘cultural appropriation’ would be ‘a passing fad’. Sadly, five years later this is clearly not the case and she was once again warning that prescriptive rules around what authors were entitled to write about were ‘anti-imagination’. She pointed out that if authors were prevented from creating characters or settings outside their lived experience, then they risk being left with nothing but memoirs. Once again it appears to be a question of the ‘antis’ attempting to police what is and is not allowed. Who are these people and why are so many so frightened of them?

On Wednesday’s Today programme on Radio 4, it was announced that Cambridge University was to become one of the first institutions in the UK to return a sculpture looted in the 19th C, from what was then the Kingdom of Benin, to Nigeria. The cockerel is one of the ‘Benin bronzes’ (most held in the British Museum), and was given to Jesus College in 1905, apparently by the father of a student. It was one of the many artefacts looted by imperial forces when the kingdom was brought to an end in 1897. Nearly 1,000 bronzes are now scattered around the world. ‘Okukur’, as the cockerel was known, used to enjoy pride of place in the college dining room until he was removed amid concerns in 2016.

It seems to have become accepted that the return of artworks to their country of origin is the ‘right thing to do’. As Master of Jesus College, Sonita Alleyne, said, it was a “historic moment and… the right thing to do out of respect for the unique heritage and history of this artefact.” Whilst I hesitate to disagree with someone as successful and respected as Ms Alleyne, I do think that this is a proposition worth further discussion. If carried to its logical conclusion, all artefacts of any artistic, heritage or historic value should in future be returned to their place of origin. Essentially, this would mean emptying the museums of the world of almost all their contents and advising those interested in viewing them that they needed to visit them in their country of origin. Is this realistic at a time when, in the name of climate change, it is being suggested that we should not all be charging around the world as tourists on a regular basis? If not, are we somehow going to be selective in which artefacts are returned? Those to do with imperialism or slavery perhaps? Those looted within the last 200 years, maybe? Those from colonised countries, as opposed to countries with which we were at war at the time? Do we perhaps need a set of key overarching principles similar to those set out in Trevor Philips report?

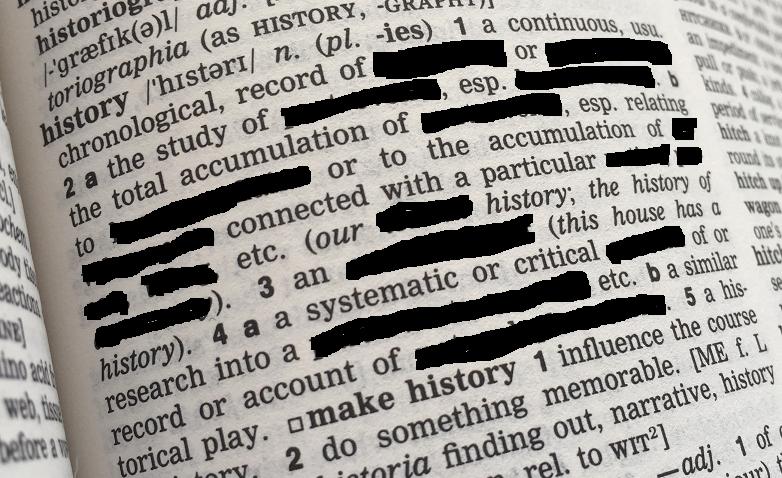

A lot of currently-fashionable views if carried to conclusion will result in unintended consequences – some of which, whilst unintended, are entirely foreseeable. We are already seeing attempts at rewriting history which many Communist countries would have been proud of. There is also a noticeable trend for TV adverts featuring an excessive number of people of colour. This may be helping to make the 3% of those who identify as black or the 6.8% who count themselves as Asian ‘see themselves reflected’ in the things they are watching, but it does not appear to accurately reflect the statistics, even if accurate up to date figures are hard to find. ( According to the government website, 87% of the UK population is white and the other 13% are of different ethnicity, but this is based on the 2011 Census data, which is clearly out of date). However, with the current focus of many of our institutions, we do appear to be running the risk of skewing not only our history, but our current view of our society.

It goes without saying that the vast majority would like to feel that all members of our society are given the respect they deserve and feel included. However, whilst attempting to redress past mistakes and ‘flaws’ (as the ROH put it), we should not lose sight of the fact that history has happened; it is past and cannot be re-made, however much we might regret many aspects of it. Instead of ‘cancelling’ those people and things of whom or of which we disapprove or whose views we do not share, we need to learn as we go forward, not keep looking backwards and attempting to right yesterday’s wrongs. The ‘classics’ are just that and represent the best of past eras. It is up to us to create the classics of the future in art, music, artefacts and technology too. They will undoubtedly be different, as they will be of our time. In the future, they too may come to represent unacceptable or unfashionable views. Who’s to know?

As Sir Ian Blatchford, chair of the National Museum Directors council and Director of the Science Museum Group put it in an article in February this year following a meeting of some 25 cultural organisations with the Culture Secretary; “While those organisations that receive public funding do have obligations to government, our most important responsibility is to our audiences. So it’s vital that those audiences can trust the stories they encounter in our spaces, in the knowledge that we aren’t seeking to skew the story to favour any particular political agenda.” Hear, hear.