19 July 2018

Claymores at Chequers

Après Theresa, qui?

by J R Thomas

Analysis of politics in these pages often tries to put things into an historical context, if only to show that there is nothing new under the sun. Scottish history has not figured much in these comparative musings but maybe the time has come that it should make an appearance.

Analysis of politics in these pages often tries to put things into an historical context, if only to show that there is nothing new under the sun. Scottish history has not figured much in these comparative musings but maybe the time has come that it should make an appearance.

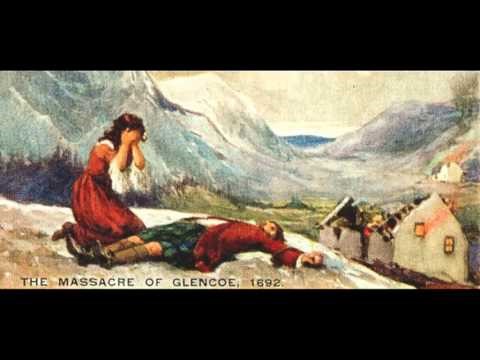

Consider the Glencoe Massacre. After the deposition of James II and the enthronement of his daughter as Queen Mary II and her Dutch husband as William III (William’n’Mary, to those whose history comes from that wonderful tome 1066 and All That) there was a struggle to enforce loyalty to the new regime, especially in those areas where Jacobite loyalties lingered strongest, well away from London and the south-east. In the end the government imposed a deadline to sign a pledge of loyalty, of 31st December 1691. The Clan MacDonald, divided amongst itself, finally signed – but after the deadline. In late January 1692, a party of Campbells, a government-supporting highland family, went to the MacDonald village in suitably grim Glencoe, where, in the ancient tradition of highland hospitality, the MacDonalds invited them to supper. The Campbells supped, and then – in a more ancient tradition – slew their hosts, whose blood (memory laments) stained the snows.

It is summer in the Chilterns and the parched grass does not show any blood. But as the Glencoe Massacre lingers in Scottish memories, and the Campbell reputation suffers still, the name of May coupled with Chequers may still be cursed in three hundred years time. With a difference, of course. It is as though the MacDonalds had fed their visitors and then attacked them. Theresa gathered together her cabinet, removed their mobile telephones to a place of safety, threatened them with whips – or at least, by the Whip’s removal of office and seats, and fed them her amended semi-Brexit vision whether they were willing or unwilling. It is extraordinary that at Chequers a group of senior ministers would allow themselves to be so treated by one who is after all merely, in constitutional terms, first amongst equals. (Mrs May seems to have rather overlooked the latter part of the convention.) It was a bizarre way to treat senior colleagues, but one which for a few hours seemed to have succeeded.

Not for long. Within forty eight hours the wheels came off. Mr Davis went, Mr Johnson (mistiming it again) went, and several junior ministers and party functionaries followed them out. Now, two weeks on, the whole thing seems to have, perhaps inevitably, misfired in the most spectacular and strange ways. The dissidents of both Leave and Remain appeared temporarily stunned by the Glencoe-lite tactics, but not anymore. There is a real current of anger in the party at Westminster. Boris is angry and that fermenting brain is out for blood. Jacob Rees-Mogg is more subtly seizing the moment. Mr Davis, speaking in the debate on Monday, was coldly cutting. Ms Soubry, standard bearer of the Remainers, was no-holds-barred dismissive of her party leadership. And if The Telegraph and The Daily Mail represent the Tory Party in the shires, there is even more fury out there.

The government whips on Monday night forced Tory dissidents into the lobbies to vote for an amendment (to destroy the Facilitated Customs Agreement) that was the key element of the Chequers plan. The Remainers then voted with all the opposition parties to try to force the government to reject the amendments brought by the Leavers to destroy Mrs May’s proposals – they lost by 4 votes. Twice Mrs May thus forced her party loyalists to effectively vote down the proposals which she herself had characterised as key to her plan to negotiate her Brexit settlement.

Can Theresa survive it all?

The answer would certainly be “no”, if it were not for one factor. It is conventionally argued that the factor that kept her in the job after the disaster of the June 2017 election was that there was and can be no agreement in such a riven party as to who might succeed her. And that even if a candidate or two could be identified, such persons would be well advised not to take the job, an almost certain route to political destruction, there being only brickbats to be gained from shepherding Britain out of the EU, and precious few golden eggs. But, is that so? There might well be an argument that Mrs May has finally solved that little problem and cleared the way for such a candidate – she has made it seem that anybody could do a better job, and she has alienated a vast swathe of the electorate who should be her natural supporters. A suitable candidate now, one who could unite most of the Parliamentary Party, one with some popularity in the country, not too controversial, with no terrible impediments in their history, must be the solution to the extraordinary bind in which government and party finds itself.

So Boris Johnson, with or without homburg and poodle (see last week’s article), it can’t be you (too controversial). Amber Rudd, it can’t be you (seen as a Remainer in the country). David Davis, it could have been you, but you apparently have no desire for further office, though the dignity and integrity of your behaviour might have swung it. Michael Gove, maybe it should be you but, dear boy, those geeky glasses and that amateur back-stabbing last year: not yet, not yet. Which leaves, to name but three; Sajid Javid, Chris Grayling, and Jeremy Hunt. It is fashionable to say that there is no talent in parliament, not like wot there were when that Lord Carrington ruled the waves, guv’nor. Lord Carrington was a fine man and a politician of great integrity, but was far from the last politician to contain those attributes. But any of these three – and several more – could do the job. Having reached bottom, the reputation of the government could only get better, and a new leader, riding that wave, would have the warm, if tentative, approval of Conservative supporters in the country.

Calls are growing for another referendum, to let the people decide. But to decide what? The original decision was close, but clear enough. From opinion polls and conversations, a rerun would simply produce a larger majority to Leave. Perhaps a different question would solve the problem. A choice between Remain and Leave on the May Chequers plan (whatever it now is)? But that is meaningless until the final EU negotiation is hammered out. Between Leaving on the Chequers deal or on No Deal at all? Maybe a three-way question, or a four-way? The Remainers want something that might cause us to remain, by deliberate decision or default, but they aren’t going to get it, and public cynicism is in danger of spilling over into the beginnings of constitutional breakdown.

So, raise battle standards, sharpen claymores, you persons in grey suits, and prepare for action. The objective is clear enough, as set out in June 2016. The only problem is the general leading the troops. And that is an easy thing for the grey-suited ones to resolve. As my colleague Lynda Goetz said in these very pages last week, the time has come that Mrs May should step down, and it is traditionally the grey suits that pay the fatal visit. Now is their time. Then the blood can be washed off the heather, a new leader committed to the best possible Leave deal (which might be No Deal) be chosen, and a cabinet be formed to deliver it. Come on Theresa, you wanted to save the Tories from being the Nasty Party. Time to show just how nice you are.