11 June 2020

Bristol’s Fallen Idol

Slavery, history and iconoclasm.

By Neil Tidmarsh

So a statue of a deputy governor of the Royal African Company has been knocked off its pedestal in Bristol. Well, good riddance to him.

So a statue of a deputy governor of the Royal African Company has been knocked off its pedestal in Bristol. Well, good riddance to him.

The restraint shown by the police was admirable. But it was a criminal act, of course, so those responsible should be arrested, charged and tried. And if found guilty, they should be given merely a nominal or even non-existent sentence. And they could wear the criminal conviction as a badge of honour.

Pulling down statues can be controversial (brace yourselves for the coming avalanche – did somebody say Robert Peel?!) but surely there’s no controversy here. No one’s trying to re-write history – Edward Colston and the source and destination of his wealth remain on the historical record. Statues don’t record history, they honour and glorify chosen bits of it. And no-one could possibly want to honour – let alone glorify – the activities of the seventeenth century Royal African Company today.

As for the controversies which will inevitably erupt as soon as today’s storm of iconoclasm really gets going, the important thing is that the iconoclasts (and their opponents) understand the history before they start to attack (or defend) the statues. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry this morning when I read that a memorial to Queen Victoria in Hyde Park in Leeds had been defaced yesterday with the words “slave owner” painted across it. Queen Victoria came to the throne in 1837 – thirty years after Britain had abolished the slave trade (the Slave Trade Act of 1807) and four years after Britain had abolished slavery itself (the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833). And the Somerset Case in 1772 had established that no one could be a slave in Britain.

In fact, for most of Victoria’s reign, Britain devoted a huge portion of its resources to the suppression of slavery around the world. And this was the Age of Empire (Victoria was crowned Empress – somewhat reluctantly on her part – in 1876); the British Empire was a fervently (even fanatically) crusading anti-slave empire.

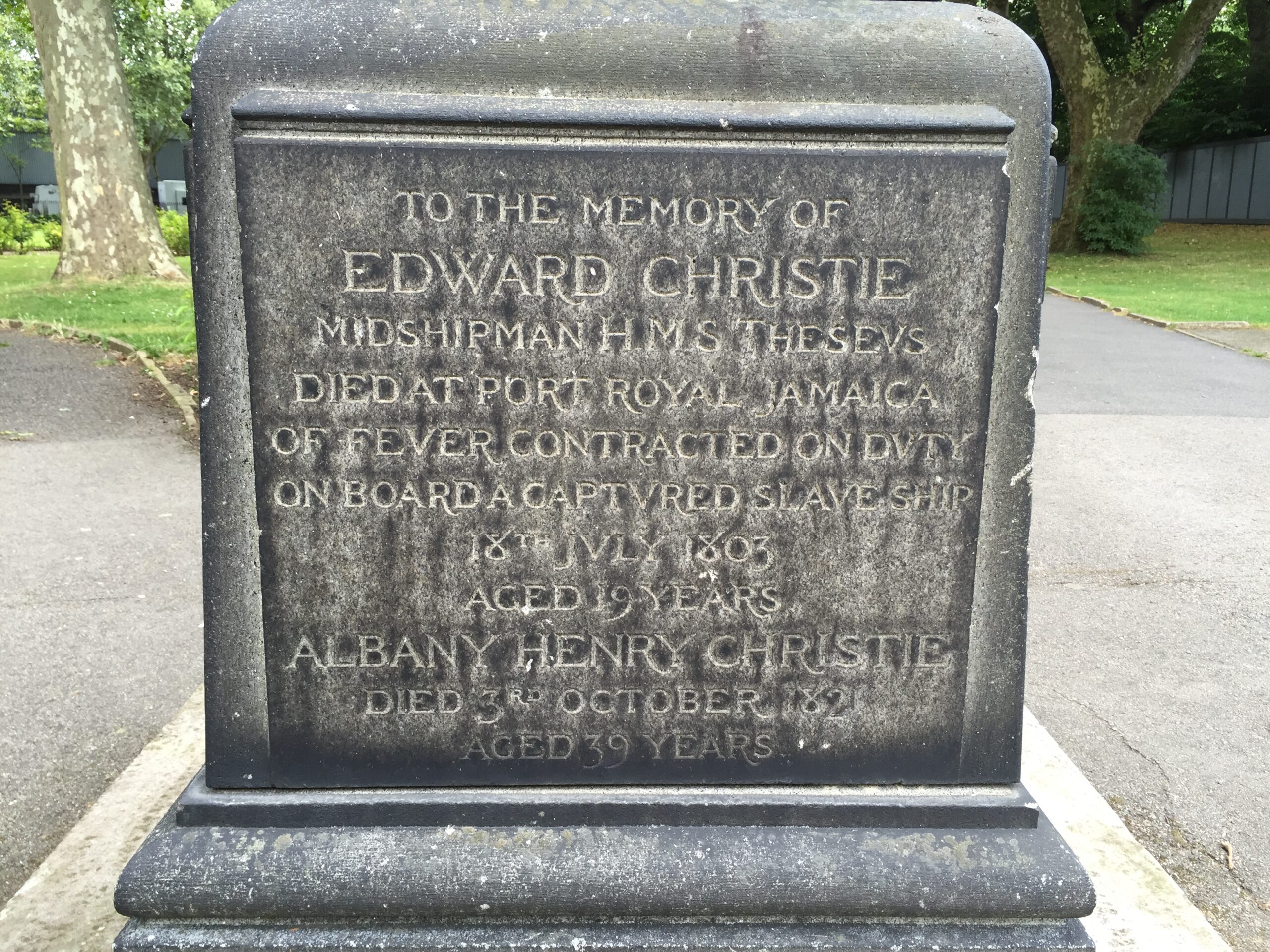

The Royal Navy waged a world war against slavers and slavery for most of the nineteenth century, taking on all comers – American, Spanish, Portuguese, African, Arabic, etc. A monument in an old churchyard hidden away behind Saint Pancras International Station has the following inscription:

“To the memory of Edward Christie, midshipman HMS Theseus, died at Port Royal, Jamaica, of fever contracted on duty on board a captured slave ship 18 July 1803, aged 19 years.”

Similar inscriptions can be found in churches and churchyards around the country. But note the year – if that’s correct, it suggests that the crusade against the slave trade began even before the 1807 Act. And according to the historian and travel writer Jan Morris, Royal Navy ships carried (anti-) slavery manuals right up until 1970!

Jan Morris’s Heaven’s Command – the first book in her three-volume history of the British Empire – describes just how forcefully the country’s nineteenth century global outreach was powered by influential anti-slavery Evangelical Christians within the British establishment (their sincerely-held ideals about the “international brotherhood of man” remain an invaluable legacy, most evident in the Boy Scout movement, founded in 1908). The British hardly set foot in the African interior before the nineteenth century; officials were interested only in ports and harbours such as Cape Town as re-fuelling depots on the way to India (and even slavers rarely went further inland than coastal trading depots). It was largely the anti-slavery crusade which first drove the British into the interior, in the nineteenth century. The clash with the Boers, though pretty shameful in every other way, was a clash between one Christian culture which believed that slavery was evil and another Christian culture which believed that the ownership of slaves was sanctioned by the Bible. Charles Gordon, that archetypical and evangelical Victorian, was appointed by the Khedive of Egypt to administer the Sudan and spent six gruelling years (1874-80) trying to stamp out slavery and the slave trade there.

Opposition in Britain to slavery and the slave-trade goes back many centuries before the eighteenth century Abolitionist movement. In the tenth century, Saint Wulfstan preached against the slave trade in Bristol and Dublin (a huge slave mart of the Vikings, who were prodigious slavers). Three centuries before that, Bishop Wilfrid freed 250 slaves at Selsey. And two centuries before that, Saint Patrick (who was himself captured and enslaved by Irish raiders) spoke out against the enslavement and mistreatment of Irish Christians by Coroticus, a British chieftain.

Saint Patrick wasn’t the only Britain to have been seized and enslaved. Many of the Vikings’ captives in Dublin must have been British, and many of those in Bristol must have been Welsh. Barbary corsairs – pirates from North Africa – preyed on British shipping throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, seizing fishing and trading vessels in the Channel and in the Irish Sea and even raiding coastal towns in Ireland and south-west England; tens of thousands of captives were taken and sold as slaves in the markets of Algiers and other lawless ports along the Barbary coast of North Africa. In his accounts of contemporary voyages, Richard Hakluyt (1551-1616) records a counter-raid to free galley-slaves from captivity in Egypt, “the worthy enterprise of John Fox an Englishman in delivering 266 Christians out of the captivity of the Turks at Alexandria, the 3 of January 1577”.

And in fact English history begins with English slaves. The first English people to be recorded in written history are slaves. In Book II Chapter i of his History, Bede (673-735) writes about the future pope Gregory (540-604) seeing some alien-looking boys for sale in the slave market in Rome. He learns that they are English, and it is this encounter which inspires Gregory with the ambition of converting the far-away English to Christianity. Curiously and significantly, the story of the encounter is centred on the issues of skin-colour, race and religion; the fairness of the slaves’ hair and skin, their foreignness and their paganism all marking them as ‘other’, from the Romans’ point of view. As a modern historian, David A E Pelteret, says (albeit in a comment about early medieval England), “slavery depends for its survival on a sense of otherness”. (And that sense is of course explicitly and deliberately opposed by that evangelical idea of the ‘international brotherhood of man’.)

There’s an empty pedestal in Bristol, and before too long there may well be many more around the country, the way things are going. A debate has already begun about what statues might replace those fallen idols. Might there be a place on just one of those vacated plinths for a statue of Midshipman Edward Christie, perhaps? Or Saint Wulfstan? Or ship’s gunner John Fox? Or even those anonymous slave boys in Rome, the first Englishmen?