6 April 2023

Are You Sitting Comfortably?

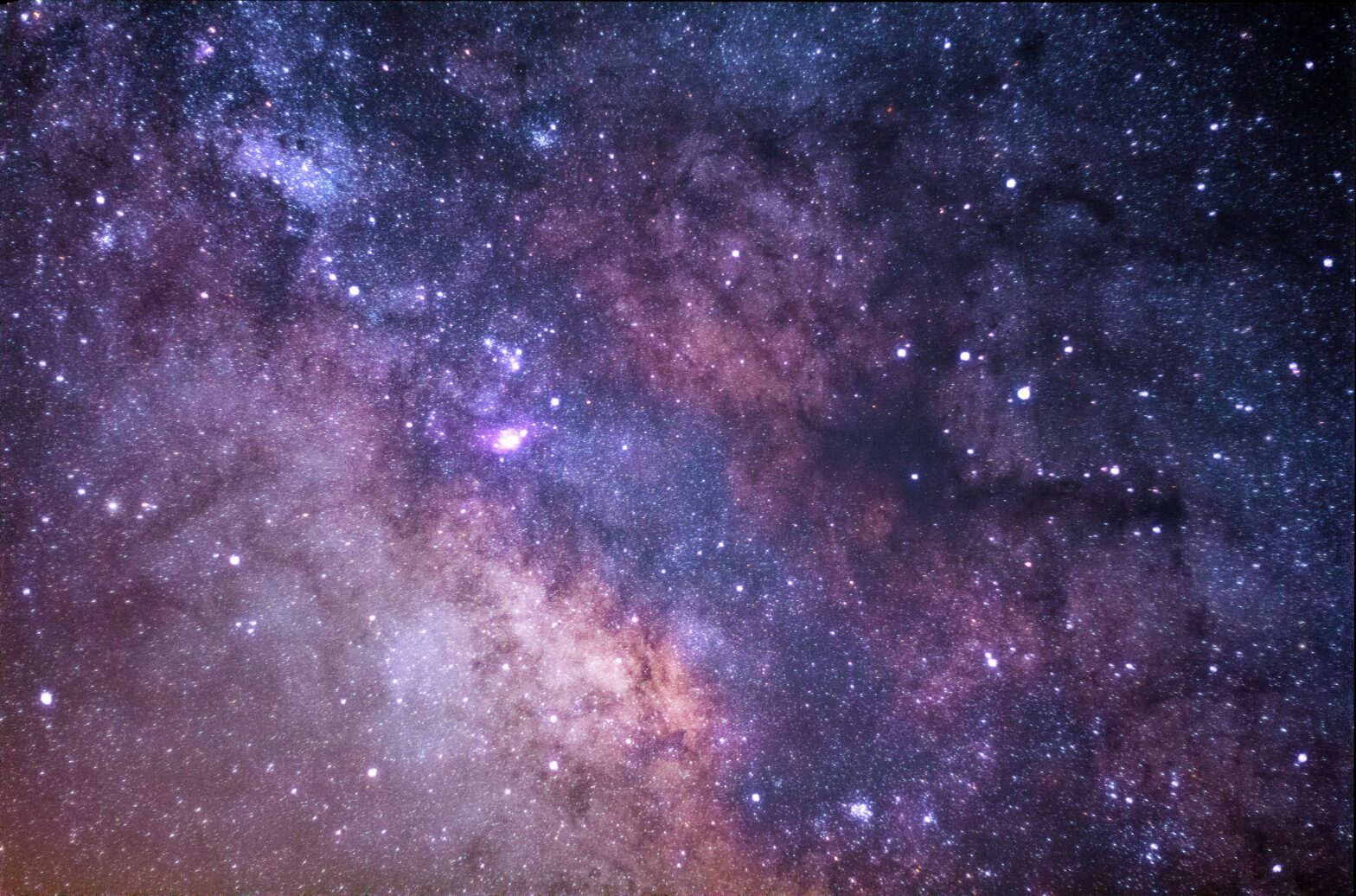

Somewhere in the multiverse.

Paul Branch

So began the iconic BBC Light Programme’s Listen With Mother, a comforting invitation from the 1950s to snuggle up, put away your childish concerns and let yourself be transported into a world of reassuring familiarity, fun and safety. “Then I’ll begin”, continued the storyteller. No dramas, nothing to worry about, all nice and logical without challenging our ingrained preconceptions and beliefs. Our world then was so easy to live in. But then it all went bang. A Big Bang in fact. A concept thought up by physicists with weird ideas about the past and how the universe all began, but with no reassuring tale to tell about how, or even when, it might all end.

All this took place within the cosy confines of our intergalactic surroundings where we on planet Earth reigned supreme, although always hoping to find traces of others to share it with. The Universe was seen as a convenient container of space and time, surrounded by an invisible protective barrier and governed by the laws of nature, as described by people of science. But some of these learned folk continued to ponder — what they saw and what they measured didn’t quite stack up with their concepts and neat equations. The combined intellectual wealth of Maxwell’s Laws of Thermodynamics, Einstein’s theories on Relativity, postulations by Planck, Rutherford, Fermi and Hawking, other wonders long since lost in the mists of time and dotage, and most recently of course String Theory still couldn’t completely explain the What, How, When of our universe, let alone the Why. Until some twenty years ago when thoughts turned to the previously unthinkable: supposing there was more than just one universe? How would it be if there were lots of them, still inhabited by us individually but with a whole bunch of different stuff going on? A multiverse, a multitude of universes all buzzing along simultaneously, out of sight but still there, doing some things better than we were but also some not so good. And of course this is where Hollywood now steps in with its block-busting awards-accumulating epic Everything Everywhere All at Once.

The movie itself, twelve years in the making, must be a good one judging by its numerous Oscars, Golden Globes and a BAFTA, not to mention eye-watering box office receipts. Its various genres beggar belief in the creativity of the screen writers: absurdist comedy, sci-fi, fantasy, domestic drama, marital relations, the meaning of life including existentialism and nihilism, millennial parental apology (a new one on me, but I can go with the flow) and several more, all wrapped up in martial arts and animation. The main plot involves its many characters inhabiting parallel universes which exist because every life choice creates a new alternative universe (one up on The Matrix of some time earlier which only had two parallel universes, if I recall correctly). There is jumping between universes, Good and Bad in all of them, a coming together of both factions, the fear that they will wipe each other out, together with the entire multiverse, and ultimately …. but I’ll leave it there at the risk of spoilerism. Hollywood at its finest it may be, however it does cover many of the issues our scientists have been struggling with since the multiverse concept first came to light.

Physicists can with some confidence trace cosmic history back to one second after the Big Bang some 14 billion years ago. It’s thought that in the first nanosecond there was enough energy released to create cosmic eternal inflation: our ever-accelerating and growing universe which looks to be relatively smooth, save for the occasional energy spikes which marked the appearance of planets and stars. What happened before that is open to conjecture, and will probably never be known with any degree of certainty – the energy needed to replicate such an event, and therefore make a positive confirmatory observation, is immense and way beyond the scientific technology available today or what may become available in the future. Some say that before the Big Bang there was nothing, merely a dark void in the form of an infinite Black Hole. Others argue that you can’t make something out of nothing, and that even with Black Holes there are traces of energy or the effects they have.

Our observable universe is sequential: there’s a past, a fleeting present (both never to be repeated), and a future. We can describe its features by means of mathematical equations which include fundamental constants, or fixed quantities in nature such as the gravitational acceleration constant (“g”, equal to 9.81 metres per second squared on Earth) or the speed of light (“c” = 300 million metres per second in a vacuum). There are around thirty such constants representing parameters within our universe, all needing to be measured and then plugged into the theoretical equations which model the nature of the universe and describe how stars, planets and ultimately humans came to exist. Altering the values of these constants by even a smidgeon would destroy our model of the universe, and us with it. So is it just good luck, a happy coincidence that the numbers align to enable us to exist at all, as some would surmise? Or could it be that we inhabit a multiverse, an infinite number of universes where different physical laws and fundamental constants apply simultaneously, where most would be unsuitable for life as we know it, but statistically speaking at least a few should be life-friendly?

In the hunt for a plausible answer some scientists have turned to the afore-mentioned String theory, which as many will no doubt be aware attempts to unify gravity and microphysics in an all-encompassing definition of most things, if not totally everything. It assumes that there are at least ten dimensions to life compared to the four we know about — three spatial dimensions plus sequential time – but these are so tightly packed together and curled up that we don’t notice the extras. Each form of compactification could be created by its own Big Bang which results in a different universe to ours, with different laws of nature. So even though we in our world can take a snapshot of our solar system, plus countless other planetary systems in our galaxy, and still more galaxies in our cosmos, all that might be just a tiny fraction of a far larger and widely diverse ensemble of universes. And worryingly, given the possibility of the existence of other time-like dimensions, individually we could be in more universes at once, not just this one, without any idea of what we’re getting up to elsewhere, or with whom, to the point of whether we’ve been born yet or even died already. However, with cosmic inflation it’s possible that different universes in a multiverse could also be able to communicate, as in the Hollywood movie, so there could be some rationalisation of our existence and our behaviour between different universes, but proving it will be a challenge.

Not to be forgotten in all this scientific meandering is the impetus the multiverse concepts give to the existence of a God, a Creator, a Grand Designer active across more dimensions than in our straitjacket of space and time. And what if we each inhabit our own universe, with just avatars or holograms for company …? All options are on the table, but as there’s not much we can do to influence the outcome one way or the other we might as well just carry on sitting as comfortably as we’ve ever done.