28 March 2019

When £1 million is not enough

Pensions, Poverty and Productivity

by Frank O’Nomics

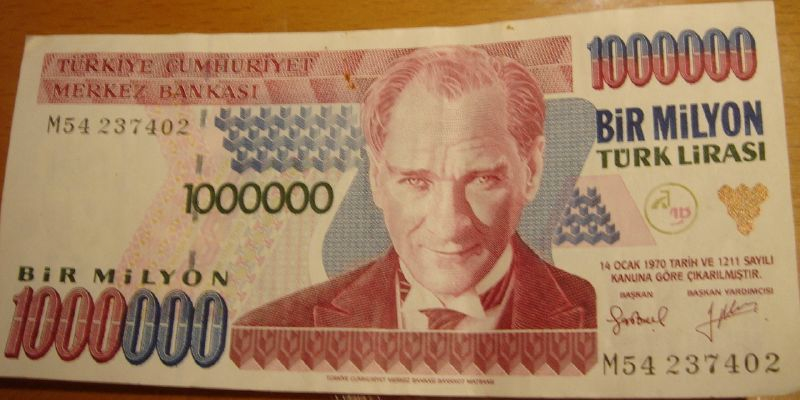

As a mild distraction (instead of watching cat videos or internet shopping) how about working out a list of the countries in which you would be classed as a millionaire? Some years ago you would have needed less than GBP 1p to be a millionaire in Zimbabwe, and even now all you need is £11,000 to be a millionaire in Indian Rupee or just over £4000 if you move further south to Sri Lanka. Once your savings get to the heady heights of £89,000 you can call yourself a millionaire in more developed countries such as Norway. Clearly this is a meaningless exercise – what really matters are the goods that your millions are able to purchase. However, surely if you can call yourself a millionaire in the UK you are still very wealthy? Think again. Those that retire with a £1mn pension pot, given the income that it can generate, are unlikely to class themselves as part of the super rich. Yet this is the maximum amount that your pension can be worth as a result of the capping of the Lifetime Allowance (£1.055mn after indexing next month) before you start to pay the onerous tax rate of 55% on the balance when you start taking your pension. The effect of this is to disincentivise saving, encourage older people to work for longer, reduce the number of doctors and other key professionals (I will explain) and perpetuate low productivity.

As a mild distraction (instead of watching cat videos or internet shopping) how about working out a list of the countries in which you would be classed as a millionaire? Some years ago you would have needed less than GBP 1p to be a millionaire in Zimbabwe, and even now all you need is £11,000 to be a millionaire in Indian Rupee or just over £4000 if you move further south to Sri Lanka. Once your savings get to the heady heights of £89,000 you can call yourself a millionaire in more developed countries such as Norway. Clearly this is a meaningless exercise – what really matters are the goods that your millions are able to purchase. However, surely if you can call yourself a millionaire in the UK you are still very wealthy? Think again. Those that retire with a £1mn pension pot, given the income that it can generate, are unlikely to class themselves as part of the super rich. Yet this is the maximum amount that your pension can be worth as a result of the capping of the Lifetime Allowance (£1.055mn after indexing next month) before you start to pay the onerous tax rate of 55% on the balance when you start taking your pension. The effect of this is to disincentivise saving, encourage older people to work for longer, reduce the number of doctors and other key professionals (I will explain) and perpetuate low productivity.

Withdrawing tax incentives on pension saving has proved fruitful for a series of governments of all political persuasion who have needed to fund spending programmes. The tax-free Lifetime Allowance was, as recently as 2012, £1.8mn, but this has been successively reduced to the current £1.03mn. While the restriction of the annual allowance was perceived to have a wider impact, the limiting of the Lifetime Allowance was expected to only affect 185,000 very rich people. However, a recent study by Sir Steve Webb of Royal London (the pensions minister in the coalition government) based on data from the ONS Wealth and Assets Survey, demonstrates that the actual number caught by the cap will be closer to 1.5mn.

So what? Surely anyone with over £1mn should be happy to pay 55% of the excess in tax? It is important to understand why a £1mn pension pot is really not that much. If you wish to use £1mn to buy an annuity to generate an income that rises with inflation and will pass to your spouse on death, the best you can do is around £25,000 a year. Adding in the state pension of £8000 barely gets you over the national average salary – hardly super rich status.

Restricting a tax-free pension pot has many consequences – few of them positive. Those retiring who still have mortgages to pay and potentially some dependents for whom they are still financially responsible are likely to face a degree of financial hardship. As a result many people are deciding to work longer. Over half of the rise in employment in the last year has been in the 50-64 age group and the over 50s have accounted for 77% of the 3mn jobs created over the last 10 years. Of that 3mn, almost 20% are over 65. There have been a number of drivers of this change. In part it is due to the removal of the default retirement age – which is generally seen as a good thing. There has also been a change due to the rise in the state pension age, particularly that for women – this is less positive as many can’t afford to retire without the state pension. The other driver has been that, even with the state pension, people can’t afford to retire. With the Lifetime Allowance cap and the likelihood of low annuity rates persisting indefinitely, this cohort is only going to increase.

Many would argue that baby boomers have had this coming. They have done well from free university studies, rising house prices and guaranteed pensions, so taxing the latter redresses the balance nicely. The problem is that this has a negative effect on society and the economy. Taking the economy first, older workers are less productive. It sounds harsh, but their lack of innovation and reluctance to embrace new ideas and technology makes an ageing workforce less than ideal. The IMF estimates that a 1% increase in the 55-64-age cohort in the workforce produces a 0.8% fall in productivity growth. Hence government pensions policy, by increasing the number of older workers, is a key element in the UK’s woeful recent productivity performance.

What about the impact on society? Here the problem is not the workers forced to delay retirement, but those who are encouraged to retire early. A great many of those who have been, or will be, unwittingly caught out by the pensions pot cap are professionals such as teachers, GPs and NHS consultants. Anyone with a final salary scheme that provides an income much over £50,000 will be exceeding the Lifetime Allowance limit (which is calculated as 20 times final salary). For many, once their pension pot gets close to the limit, there is little point in carrying on working if they are not going to accrue any meaningful additional pension benefits. Teachers and doctors may be the one group of older workers who are actually more productive than younger colleagues, given the importance of experience in those professions. Further, these are areas where skill shortages are seen as becoming ever more acute over the next 10 years, meaning that staff retention is paramount.

Pensions have been seen as a soft target for governments which have to find ways of balancing budgets. The negative consequences outlined here are unlikely to be well received given the ongoing need to raise money and it is more likely that further constraints on pensions (probably a further cut in the annual allowance) will feature in future Budgets. For those who can do so, finding ways tax effective ways to save outside of their pension may be advisable. For the rest a longer working life is in prospect. The Treasury has said that it is important to strike the right balance between encouraging people to save into a pension and managing government finances – the evidence suggests that they have got this balance wrong.