28 July 2016

Betty Botter’s Example

A treatise on nutrition.

By Chin Chin

As readers of the 1899 Jingle Book will tell you, Carolyn Wells wrote:

‘Betty Botter bought a bit of butter;

“But,” she said, “this butter’s bitter!

If I put it in my batter

It will make my batter bitter

But a bit of better butter

Will but make my batter better.”

So she bought a bit of butter

Better than her bitter butter,

Made her bitter batter better.

So ’twas better Betty Botter

Bought a bit of better butter.’

Well, it is great as a tongue-twister, but from a culinary perspective you cannot help wondering if Ms Botter was making some terrible mistakes. Wouldn’t the batter have tasted still better, for example, if she had thrown out the bitter batter and started all over again? Surely a nineteenth century Mary Berry would said:

“No, dear, this isn’t really very good batter, there is something nasty in it.”

You would have thought that the bad butter would in some way have tainted the flavour of the rest – rather like the teabag which only this morning I absent-mindedly dropped into my cup of coffee. Of course we know little of Ms Botter’s circumstances. Perhaps she could only afford a small quantity of better butter – just enough to be able to pass the batter off as a “unique new healthy flavour,” rather than as a mistake. We are short of evidence here but at least we can come to the conclusion that if she could have afforded it she might have done better to throw the old batter away.

But the questions raised by Ms Botter’s actions go far beyond mere flavouring. Why was the bitter butter bitter and how did it differ from the better butter? Did the latter have sugar added, which made it less healthy for the eater? We all know now – or at least we think we do – that the primary cause of obesity and its related diseases is eating sugar rather than eating fat. Did Ms Botter’s action in substituting sweeter butter for bitter butter set a bad example and thus endanger the public health of the nation?

Actually, we had only just stopped celebrating the recent “fat is okay” verdict when other studies emerged saying that we would be even healthier if, rather than eating normal fat, we ate fats which are polyunsaturated. To be honest, I have no idea at all what that means, and my attempts to crack the code by taking the word apart only yielded an unhelpful reference to dry parrots. I think I’m right in saying, however, that the basic rule of thumb is now: “butter is good but olive oil is better”. That in itself is fairly Delphic. What does “good” mean? Something better than “sugar,” I suppose, but presumably not as good as olive oil based margarine.

How much “better” polyunsaturates would have been presumably depends on the other constituents of the Botter diet. What else was she eating and in what form was she eating it? Were there other parts of her diet which were deficient? Nowadays one of the medical profession’s main concerns seems to be a deficit of Vitamin D, something which can be remedied by long exposure to sunlight, hard to find in the iconic Victorian smog – there were no sunbeds in Betty’s day which was probably a good thing since otherwise she would have died from skin cancer before she got the chance to savour the better batter, vitamin D pills (hard to find in a Victorian chemist) and eggs.

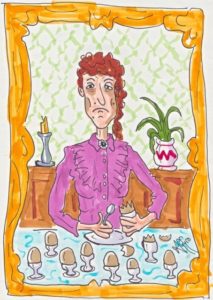

According to recent research you can eliminate your Vitamin D deficiency by simply eating ten eggs a day. “Simply” is perhaps the wrong word to use here. Ten eggs sounds like a challenge and possibly dangerous, although in the film Cool Hand Luke Paul Newman ate 50 in an hour and then he survived to continue acting for many more years. Still, there is the practical question of how you would eat them. Ten boiled eggs standing in a row with strips of toast: soldiers at two levels so to speak? Three large omelettes? You certainly wouldn’t want to share a railway compartment with someone who had eaten either combination. Maybe Betty Botter ate her eggs in the batter.

Archaeologists will tell you that it is often difficult to draw real lessons from ancient ruins because of the paucity of the evidence. In deciding what we should eat, there are plenty of reports and studies but the problem is that the evidence is contradictory and confusing. How then should we treat this important fragment handed down orally from generation to generation since the end of the nineteenth century? Should we dissected it word by word in an attempt to reach back to the instinctive dietary wisdom of our forefathers? Should we program computers to compare it against other sources of the same period and see whether it agrees with them?

We could do either, but I think I have a better idea. Recite it out loud in your car on a long journey. Then get your family to recite it with you. Then do it all rather quicker. After a bit you can get out your watch and see which of you can do it quickest. It may not teach you a great deal about cooking or nutritional science, but it will still contribute to the family’s health and well-being. After all, it will greatly reduce the temptation to beat your children to death for spending the hours it takes to complete a scenic drive through the mountains with their eyes firmly glued to their computer games.

If you enjoyed this article please share it using the buttons above.

Please click here if you would like a weekly email on publication of the Shaw Sheet