29 April 2021

A Stellar Legacy

By Paul Branch

Sixty years ago this week, in 1961, the then recently elected President John F Kennedy became embroiled in an international incident the USA didn’t want, certainly didn’t need and to this day the memories still linger on. A band of dissident Cuban refugees attempted a coup to overthrow the communist regime of Fidel Castro in the notorious invasion of the Bay of Pigs, with the tacit blessing of the CIA. They were allegedly promised an air strike to help them on their way, a promise that Kennedy withdrew at the last minute for fear of upsetting the international community, in particular Nikita Khrushchev, head of Cuba’s principal ally, the USSR. With no warning of the loss of air cover, the exiles were left to their fate: many were killed, or imprisoned and then executed, and Castro continued to reign supreme for another fifty years.

Sixty years ago this week, in 1961, the then recently elected President John F Kennedy became embroiled in an international incident the USA didn’t want, certainly didn’t need and to this day the memories still linger on. A band of dissident Cuban refugees attempted a coup to overthrow the communist regime of Fidel Castro in the notorious invasion of the Bay of Pigs, with the tacit blessing of the CIA. They were allegedly promised an air strike to help them on their way, a promise that Kennedy withdrew at the last minute for fear of upsetting the international community, in particular Nikita Khrushchev, head of Cuba’s principal ally, the USSR. With no warning of the loss of air cover, the exiles were left to their fate: many were killed, or imprisoned and then executed, and Castro continued to reign supreme for another fifty years.

In October of that same year the world was treated to the Cuban Missile Crisis, a stand-off between Khrushchev in the red corner with his shipment of missiles sailing for installation on America’s front doorstep, and Kennedy in the blue corner directing his blockading warships to greet them and see who blinked first. The world held its breath, hid under tables and desks in preparation for nuclear Armageddon, and breathed huge sighs of relief when the USSR decided that enough was enough. The Cuban missile installation was taken down, no new warheads were despatched, but in return the USA quietly agreed to dismantle its own Jupiter missile facilities in Turkey and Italy, which had been another contributor to the disagreement between the two Super Powers.

Quite a first year for the young President Kennedy. His term of office ended prematurely and tragically, but he did manage to squeeze in another exceptional event in between the other two in 1961: a historic speech calling for his nation to rediscover its traditional pioneering spirit, culminating in an exhortation to support NASA’s Apollo programme: “We choose to go to the Moon”. And they did. In July 1969, on schedule, Apollo 11 started a period of three years of seemingly continuous evening TV entertainment as US astronauts cavorted on the lunar surface. A token flag was planted, the lunar rover was deployed, the Earth was seen rising over the Moon’s horizon, even golf was played (Alan Shepherd hit a six iron shot, but only 40 yards or so – not bad from a dust bunker though, with a converted soil sampling instrument and wearing a somewhat inflexible spacesuit). And there was drama with the aborted Apollo 13 mission’s nail-biting ride back to Earth in a converted lunar module, serving as a lifeboat following an oxygen tank explosion in the command module. All this with technology that we wouldn’t give houseroom to today. As an example, the Apollo 11 computer processor speed was 43 kHz, compared to today’s iPhone capability estimated at 2.5 GHz or nearly 60,000 times faster.

Aside from bringing home samples of black moon dust for geophysicists to pore over, Apollo led to great strides in the advancement of avionics, jet propulsion, electronics, telecommunications and computers to the general benefit of the rest of us. Perhaps just as important to the USA was the great sense of pride from the programme in the achievement of technical excellence, and in their technical leadership. But then the excitement waned and NASA funding became more difficult to justify in the face of competing domestic priorities, only to perk up as the realization dawned that America was no longer the clear leader in innovation. India had become a software powerhouse, a rejuvenated Russia was demonstrating great strides in military firepower, and above all China had become a menacing presence in the drive for cybernetics mastery. So, where to next in America’s journey into space?

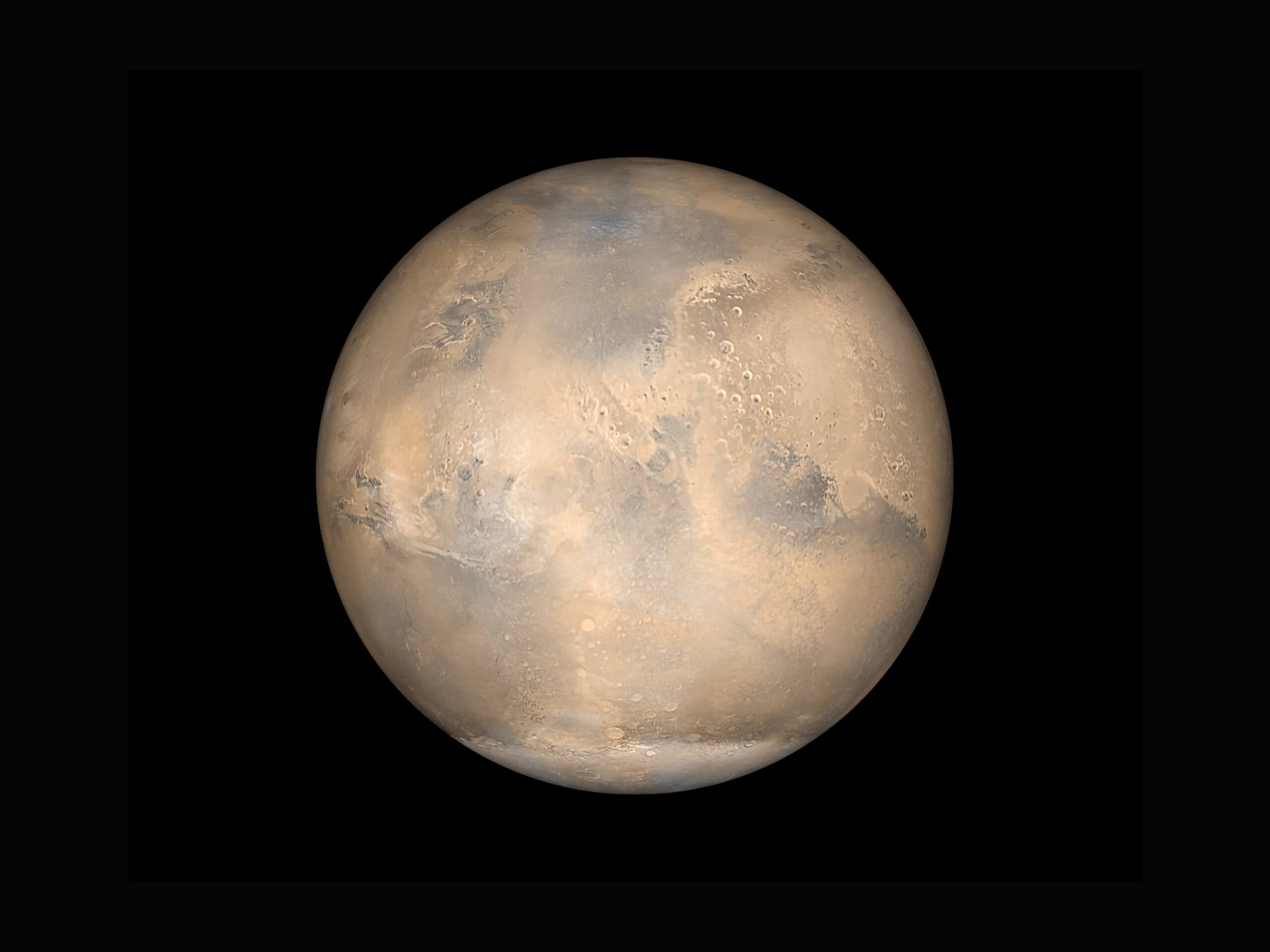

As well as the Moon, there have been other spacecraft missions notably to Venus, Mars, and Saturn’s moon Titan. No one’s thought of visiting Jupiter, the largest member of our solar system after the Sun, mainly because there would be nothing to land on. It’s mostly hydrogen and helium, no oxygen, and entry into the gravity-laden atmosphere would be at a tad above 100,000 mph as the denser layers approach. It spins like a merry-go-round (maybe a slight exaggeration: one day lasts just under 10 Earth hours) creating winds that get up to 300 mph, and closer to the surface the pressure increases from 100 to 1000 and then 2 million times that of the Earth. All radio waves would be absorbed, and finally it’s hot …. very very hot. As alternative places to visit, Venus or Saturn are no more attractive, so Mars it was then.

It’s been less than three months since NASA’s Perseverance robot vehicle landed impeccably on Mars and began its scientific activities. Already there have been a couple of firsts to justify an email home, the main one being the conversion of some of the thin, 96% carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere into oxygen. Although obviously needing development for production in quantity, this would be a breakthrough for future landings or indeed for the establishment of the farthest-flung outpost of the US empire, were such a thing permitted under terrestrial international law. Its weight in canisters means you can’t really take enough oxygen with you to serve two main purposes. The first is to produce air so as to carry on breathing once you’ve arrived, and the second is to produce rocket propellant to help power your return to Earth. The waste product from the oxygen conversion process is carbon monoxide which, somewhat ironically, just gets dissipated into the Martian atmosphere …. no qualms then about starting to pollute someone else’s planet as soon as we’ve arrived, but I suppose the context and the scale are a little different to the situation back here on Earth.

The other notable achievement has been the successful flights of Ingenuity, the little Mars helicopter/drone which last week rose to a height of 5m before leaping off for 50m across the Martian terrain then coming back to its original position. 80 seconds flight time isn’t enough for a duty-free G&T, but it was certainly good enough to mark another record distance after the initial historic attempt which saw the first powered, controlled flight by an aircraft on another world. The helicopter’s main task will be to take photos to send back to NASA. It weighs just 1.8 kg, but it needs to be light as the thin atmosphere impedes the ability to produce lift, even with the lower gravity on Mars. The solar-powered vehicle comes complete with rotor blades turning at 2500 rpm, batteries, avionics, sensors, camera and an antenna for relaying the photos. Given that it takes over a quarter of an hour for radio signals to traverse the 295 million km between Mars and the Earth, the little chopper has to conduct its missions autonomously – there’s no opportunity for Houston to overcome any real-time steering issues with a joystick for example.

And so JFK’s stellar legacy lives on, extended beyond our previous lunar boundary to another part of the celestial universe, increasing our knowledge of the Cosmos and hopefully also the awareness of our role in sharing the benefits of mankind’s discoveries. He would no doubt have been familiar with the song made famous by his Ol’ Blue-Eyed friend who crooned:

Fly me to the Moon

And let me play among the stars.

Let me see what spring is like

On Jupiter and Mars …..

… but probably best to leave Jupiter alone for a while yet, Frankie.

Tile photo: NASA on unsplash