15 October 2020

Stormzy’s Approach

Not just BAME.

By John Watson

Just occasionally a perfectly good name or acronym gets so overused that it begins to obscure rather than throw light on the circumstances to which it is applied. The term “racism” is a good example, much thrown about but meaning different things to different people. Another is the term “BAME”, the acronym for Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic people and the issue there is that it groups all non-white people together as if the issues which they face were the same, when clearly that is not the case at all.

Just occasionally a perfectly good name or acronym gets so overused that it begins to obscure rather than throw light on the circumstances to which it is applied. The term “racism” is a good example, much thrown about but meaning different things to different people. Another is the term “BAME”, the acronym for Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic people and the issue there is that it groups all non-white people together as if the issues which they face were the same, when clearly that is not the case at all.

Like most other countries, England has a long history of immigration and there is a clear, albeit gradual, process which takes place. First immigrants arrive and establish networks amongst themselves and with those of a similar cultural background who are already here. Second they form links with the main community through employment, education, intermarriage etcetera and at that point their culture begins to merge with ours. Eventually they blend in so thoroughly that their distinction from the local culture is marked only by family history, traditions and perhaps religion. In time, of course, these distinctions too disappear, so that ultimately the ripples from the wave of arrivals are found in changes to the genetic make up and cultural stream of the nation as a whole, individual ancestry being left to genealogical TV shows.

How quickly this happens depends upon lots of different things: how similar the arrivals are to those already here, how adaptable they are, how much effort is made by the locals to draw them into the mainstream and many other things too. What is clearly not true is that all immigrant communities are at the same stage of the process or that the problems facing them are the same. To lump them together under the heading “BAME” fails to acknowledge the difference between the journeys they have to take and, unless one is very careful indeed, gives rise to the lazy thinking which undermines attempts to reduce racial disadvantages in modern Britain.

For evidence that the different communities face different problems you do not have to look far. At page 3 of the Lammy Review which dealt with outcomes for minority groups under the Criminal Justice System (and which for the record uses the expression “BAME” with commendable care) there is a brief comparison of educational achievement of the various ethnic groups. “Chinese and Indian pupils outperformed every other group, while Pakistani children are likely to struggle. Black African children achieve a better GCSE exam results on average than Black Caribbean children.” Clearly the way in which these communities are pushing their way towards the top table in British life differs. You get the same message from the ethnic make-up of the prison population. Although only 3% of the general population, Black people made up around 12% of the adult prisoner population in 2015-16 and more than 20% of children in custody. That compares with Asians where the level of prisoners is less than that for the population as a whole and, as Lammy goes on to comment; “within categories as “Asian” or “Black” there is considerable diversity with some groups thriving whilst others struggle”.

So what should we make of Legal & General’s decision not to support companies who have no BAME member of their board by 2022? Will it help those communities who are having trouble integrating or will it simply increase the access to the top table for those communities which are already throwing up large numbers of well-educated people who will naturally get there anyway? If the latter, is it any more than virtue signalling?

If the application of the stick is ineffective because of the difficulty of accurate targeting, the problem has to be approached from the other end by enabling the more disadvantaged communities to produce people, important in the nation as a whole, to act a role models. There are currently two very senior members of the government who are of Indian extraction and that must surely reinforce the message to the youth of that community that they can penetrate the British establishment and that the work they invest in their education will be repaid.

Other communities have their own heroes – David Lammy being one himself of course – who hold their position not because of some social engineering by an insurance company but because their skills justify it. The trick of integration is to encourage more of them and to do so in a way which encourages the particular communities who need it and not just BAME.

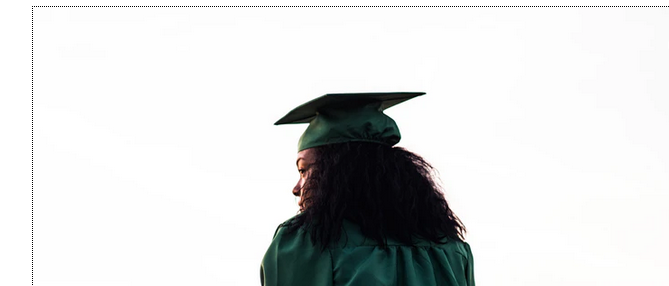

That is why the contribution made by the musician Stormzy, who sponsors two Black, “Black” not “BAME” mark you, undergraduates to Cambridge has so much potential. It gives them the opportunity to stand out as beacons of hope for their community, treading a path which others can follow, and, at the same time, making Britain as a whole more comfortable with seeing diversity at the top. I have not met Stormzy and am by no means convinced that we would get on if I did, but his solution, which he backs with his own money, seems far more likely to contribute to a multiracial Britain than that espoused by L&G.