23 May 2019

Notre Dame

Back to the future?

By Richard Pooley

You learn a lot about a people’s culture when they are hit by a disaster, natural or man-made. In late 1994 I was staying with Swiss friends in Kobe, Japan. The couple and their two children had just moved there from Tokyo. As we looked down on the city’s port from their terrace, they told me how relieved they were to be away from Tokyo and the ever-present threat of a severe earthquake. Kobe, they had been assured, did not have a history of strong earthquakes. On 17 January, 1995, an earthquake destroyed their house, one of nearly 250,000 buildings which collapsed. They survived, unlike 6,434 other residents of Kobe, and were not among the 43,794 injured. But they left Japan soon after, a decision largely driven by their disgust at the way the Japanese authorities responded to the disaster.

The nearest base of the Japanese army (sorry, their “Self-Defense Force”) was a few kilometres the other side of the mountain range from the city. But no soldiers came to help for the first 24 hours because the unit was waiting for orders from Tokyo. Instead, hundreds of lives were saved by taxi-drivers, who were ordered by Kobe’s Yamaguchi-gumi gangsters to ferry the injured to those hospitals which were still standing. Many of the elevated expressways collapsed because the yakuza, who control much of the Japanese construction industry, had forced contractors to cut corners and bribed officials to accept sub-standard work. But Kobe’s citizens and local media saw the gangsters as their saviours. The US Navy had a ship offshore and immediately offered to send doctors, medical equipment, blankets and medicines. The Japanese authorities refused: Gaijin doctors would not understand Japanese bodies. Expert tracker teams with dogs were offered by several countries. No, said the Japanese, the dogs would have to go into quarantine. The real reason, as my Japanese colleagues admitted, was that the government could not bear the loss of face that accepting such help would involve. The sorry response to the even more destructive and deadly earthquake and tsunami further north in March 2011 showed that lessons were not learned from Kobe. Culture ruled.

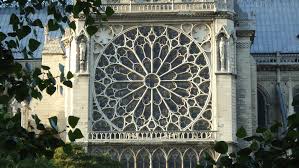

The disaster that hit the French on April 15 – the fire which destroyed the spire and much of the roof of Notre Dame cathedral in Paris – was man-made and not fatal. But the response to it and the debate as to how it should be restored has revealed a lot about the French. As I wrote at the time, the shock and grief was palpable in my village, 500 km to the south. I doubt if villagers in Cornwall or Lowland Scotland would feel the loss as deeply should the same ever happen to Westminster Abbey. I was sad when I heard about the fire which destroyed much of the roof of York Minster in July 1984. But I didn’t cry as I witnessed people do here. Notre Dame is France. Get to know its history and you will have a good grasp of the history of the French people.

Another response was even more startling, at least to me, an expat Brit. Within hours of the fire huge donations of millions of euros were being promised by some of the country’s richest people and largest companies. Mayors around France offered money from their town hall budgets. Many communes in areas with oak forests promised to provide timber to replace those lost in the fire (some 3000 oak trees went into that roof, many of them cut down in the decade after 1160; to reach the size needed, they would have started life in the 9th century AD). Individuals too were promising to donate. In my experience, giving to charities does not come easily to the French. They can be generous but usually to local organisations with which they feel a connection. In six years I have never been pestered in village, town or city by anyone asking me “to complete a survey” or to drop money into a charity tin. Yet here they were, offering millions; €850 million so far. The trouble is that only €71 million has actually been donated to date. Some of those mayors have been forced to withdraw their offers by furious residents of their towns. For example, the mayor of Dammartin-en-Goële, a commune of some 10,000 people on the edge of Paris, promised €2600. But as one local opposition politician put it: “How come now, by some miracle, thousands of euros have been found to help Notre-Dame?” The mayor has backed down and says the money will instead be used “to restore several little 13th century chapels.” (Mind you, I can’t see €2600 going very far if the prices charged by stonemasons in Dammartin are similar to those demanded by their colleagues in my area).

I suspect that a major reason why relatively little of the money promised has been handed over is because many people had second-thoughts once they had got over their initial shock. Why give money when millions have already been offered by the rich? What difference will my pittance make? Those rich people are only doing it because they get a massive tax break – 66%! Amazing, isn’t it, how Macron says there is no money to help out us ordinary folk but his rich cronies can throw money at Notre Dame. Anyway, it’s the job of the State to restore it. Only that final sentence I have not heard over the last month. Yet, I reckon that it is a view held by every French person I know. Even the French government’s promise to give a 75% tax break for donations up to €1000 has not opened French wallets.

And so to the great debate which still fills many television and radio hours, uses up a lot of newsprint, is big on social media and, on 10 May, resulted in a bill being approved in the National Assembly (admittedly with only 47 out of 577 deputies physically present to vote; but they had been debating for 13 hours poor souls). No, not President Macron’s Grand Debat, his response to the gilet jaune protests. He was due to tell the French what conclusions he had drawn from that debate on the night of the fire. He got round to doing so a few days later but it somehow got lost in the noise still surrounding what had happened to Notre Dame. The key question being discussed with passion, if not always much logic, is this: Should the cathedral be restored to exactly what it was moments before the fire, or should the roof area be an innovative and inspiring example of the best in 21st century architecture?

What has received far less attention is what caused the fire. There is an enquiry, of course, but the French media seem content to let it get to the truth without a blame game running in parallel. Contrast that with the reaction in Britain to the destruction of London’s Grenfell Tower by fire. Is this difference solely because so many people were killed in the London fire? Or is it also because there are no easy targets to blame: a rich yet heartless and incompetent council, those big, bad construction companies? Or is it because the likely culprit is an artisan (wearing his gilet jaune?) who flicked away his cigarette (a Gauloise bought on-line?) without ensuring that it was not still alight?

So, to that main question. I asked a London-based British architect, Colin Mendelowitz, for his view:

“Many conservation purists are calling for a ‘like for like’ reconstruction, rebuilding the roof using the same materials that were burned away. This is folly. The French oak trees that would be required to be felled, sawn and seasoned simply don’t exist any more. Such trees were used up long ago. To pursue a massive logistical exercise to source oak from around the world in sufficient quantities and sizes would be alarmingly expensive, time-consuming and probably constitute an environmental crime.

There have been the most amazing advances in structural material and building fabric design since the 19C restoration. These should now be employed in the hands of our finest designers to create a new cathedral befitting the 21st Century.”

I agree. And so do most of the architects who have flooded the media – mainstream and social, national and foreign – with their views and proposed designs. Colin particularly likes the proposal by French architect Vincent Callebaut (see it here): “Inspired by environmental issues, he re-imagines the roof of Notre Dame Cathedral as a solar-powered urban farm.” Roof and spire would be made of glass. The spire would replace the one completed by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc in 1859, which recalled the original fatter, shorter one built in the 13th century but removed because of wind damage in 1786. Callebault describes his spire as “a new symbol of spiritual aspiration”. The iron rooster which crowned Viollet-le-Duc’s spire survived the fire. Callebault would put it back on top: “It should remain the spiritual lightning rod and protector of the faithful.”

Ah yes, the faithful. In all the heat and passion of the debate it is easy to forget that we are talking about a church. Certainly, the views of Roman Catholics in France have not received much publicity. And I find little mention of the religious purpose of the building in the discussion among French intellectuals. Le Figaro, a conservative newspaper, which probably has a large number of practising Roman Catholics among its readers, found that 70% of the 35,000 people it asked were opposed to a contemporary design. They want it restored to how it was. So do the majority of French people; 54% according to a YouGov poll.

What will happen? I think the architects and intellectuals will win and we shall get an innovative design using modern materials. However, this will not be because they have argued their case well but because restoring the roof and spire to what it was is impractical if not impossible. Are we really going to find and put up 750 tons of lead-coated oak, which is what the spire consisted of? Callebault is at least understandable. But try getting your head round this from one commentator defining “restoration”: “Both the word and the thing are modern. To restore an edifice means neither to maintain it, nor to repair it, nor to rebuild it; it means to re-establish it in a finished state, which may in fact, never have actually existed at any given time.” The man was, in fact, quoting Viollet-le-Duc’s definition of restoration. As so often in France, the intellectual elite are talking above the heads of us groundlings.

Colin (a British intellectual?) argues that we should see Notre Dame as a palimpsest, the wax-coated tablet used by Ancient Greeks and Romans to write on with a stylus. They could write something new by smoothing out the wax and starting again. So with buildings, which are “created for one purpose and then become re-inhabited, modified and reused as befits the time and circumstances. The term ‘adaptive re-use’ is often used by us architects.” He points out that Notre Dame was “started in 1163, completed (sort of) in 1250 and altered in various ways over the next few centuries until a major “restoration” finished in 1864. We should embrace the idea of adaptive re-use and let Notre Dame contribute more to Paris than being a house of prayer with picture postcard credentials.”

Hear, hear.

I was rude about the Japanese at the start. Perhaps though we can learn from their attitude to their religious buildings. The Ise shrine, the most important Shinto site in Japan, is so sacred that no commoners are allowed inside. It is dedicated to the sun goddess Amaterasu, from whom the Japanese emperors are believed by many Japanese to be descended. Its High Priestess is the sister of the new emperor. The two main shrine buildings, constructed of cypress wood and using no nails, are rebuilt in their entirety every 20 years. The present buildings were finished in 2013 and are the 62nd iteration. Do the math. Why are they rebuilt? It reflects the Shinto (and Buddhist) belief in reincarnation and the impermanence of all things, not surprising when earthquakes, tsunamis and volcanic eruptions are so frequent and so deadly: “the buildings will be forever new and forever ancient and original”.

It is also a way of handing down building techniques from one generation to the next. Although the specifications as to what materials and skills are used are exacting, this does not mean they are never changed. Far from it. The influence of Buddhism on Shinto, and Japanese culture in general, has resulted in ever greater use of gold and copper adornments over the centuries. When the best quality local wood ran out long ago, they began sourcing from other areas of Japan (but only Japan). Sounds like adaptive re-use to me.