27 September 2018

MEP’s Accountability

Expenses a privacy issue?

By Lynda Goetz

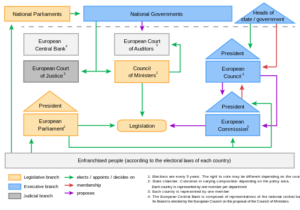

For some, the idea of a public office with an expense account in the region of £4,000 a month (exclusive of refunds on first-class travel expenses and a daily living allowance of €313 when working in Brussels or Strasbourg) on top of a salary of double that amount (and pension paid on top of that) would be the stuff of fantasy. Add to that the fact that there is no accounting for any of it, and one might expect the Cheshire Cat to appear at any time. This however is how the EU works. An attempt by a group of European investigative journalists to bring some transparency to the system was thwarted this week when an appeal to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) failed to overturn a decision by the European Parliament that MEPs expenses should remain secret.

For some, the idea of a public office with an expense account in the region of £4,000 a month (exclusive of refunds on first-class travel expenses and a daily living allowance of €313 when working in Brussels or Strasbourg) on top of a salary of double that amount (and pension paid on top of that) would be the stuff of fantasy. Add to that the fact that there is no accounting for any of it, and one might expect the Cheshire Cat to appear at any time. This however is how the EU works. An attempt by a group of European investigative journalists to bring some transparency to the system was thwarted this week when an appeal to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) failed to overturn a decision by the European Parliament that MEPs expenses should remain secret.

As we all know, MPs in this country have long had to account for their expenses, although not until 2009 did the public have access to this information, when the parliamentary expenses scandal led to the formation of The Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority (IPSA). Some MPs feel that this regulatory body is cumbersome, expensive and fails to provide a full solution to the problem of expenses and transparency. Sir Peter Bottomley, MP for Worthing West, and Tom Harris, the former Labour MP for Glasgow, were both vociferous opponents of IPSA. Harris’s Telegraph article in 2013 made clear his problems with the way it worked. Clearly, in order to do their jobs, MPs need to pay for offices, staff and accommodation, inter alia. Prior to IPSA they did have to account for these things, but only to an internal audit office, and scrutiny was minimal – hence the abuses uncovered by The Telegraph in 2008. It would appear, according to the journalists’ investigation, that similar abuses are going on under the direct payment system currently used by the European Parliament.

It is easy to see why the expenses allowance (destined, supposedly, for MEPs to run a national office ‘for closer liaison with their communities’) is paid directly. That way a further layer of bureaucracy is avoided (IPSA has 50 employees) and the MEPs and their staff do not have to waste time submitting endless bits of paper to justify what they need to spend on running a national office. Human nature being what it is however, such a system is open to abuse. It is fine for the European parliament to defend the privacy and the integrity of its MEPs, but not all of these are immune from the temptation to game the system. Thus, for example, some MEPs own the building in which their office is located – so of course they need to pay themselves rent. Others, apparently, do not in fact run an office at all – although unsurprisingly, as there is no requirement to do so, they do not return the expenses allowance to the EU.

It is easy to see why the expenses allowance (destined, supposedly, for MEPs to run a national office ‘for closer liaison with their communities’) is paid directly. That way a further layer of bureaucracy is avoided (IPSA has 50 employees) and the MEPs and their staff do not have to waste time submitting endless bits of paper to justify what they need to spend on running a national office. Human nature being what it is however, such a system is open to abuse. It is fine for the European parliament to defend the privacy and the integrity of its MEPs, but not all of these are immune from the temptation to game the system. Thus, for example, some MEPs own the building in which their office is located – so of course they need to pay themselves rent. Others, apparently, do not in fact run an office at all – although unsurprisingly, as there is no requirement to do so, they do not return the expenses allowance to the EU.

The General Expenditure Allowance (GEA) of €4,416 (tax-free) a month is paid in addition to up to €24,164 for office staff. This latter amount does have to be fully accounted for. (An excellent guide to MEPs salary and allowances is given by Scottish MEP Alyn Smith on his website). Many of the MEPs themselves feel the need for more transparency and were disappointed by the decision in July by the Parliament to block attempts to tighten the rules around the GEA. Heidi Hautala, a Vice-President of the European Parliament from the Finnish Green Party, expressed dismay that certain political groups were ‘not listening to everyday people’s concerns about how tax-payers money is being spent’. The plan for reform had been worked on for months and was submitted to the 15-member bureau, which is the governing body for the Parliament, who rejected it in a late behind-closed-doors meeting. That decision was backed by the ECJ on Tuesday.

The General Expenditure Allowance (GEA) of €4,416 (tax-free) a month is paid in addition to up to €24,164 for office staff. This latter amount does have to be fully accounted for. (An excellent guide to MEPs salary and allowances is given by Scottish MEP Alyn Smith on his website). Many of the MEPs themselves feel the need for more transparency and were disappointed by the decision in July by the Parliament to block attempts to tighten the rules around the GEA. Heidi Hautala, a Vice-President of the European Parliament from the Finnish Green Party, expressed dismay that certain political groups were ‘not listening to everyday people’s concerns about how tax-payers money is being spent’. The plan for reform had been worked on for months and was submitted to the 15-member bureau, which is the governing body for the Parliament, who rejected it in a late behind-closed-doors meeting. That decision was backed by the ECJ on Tuesday.

Whilst €40m may be a drop in the ocean in term of EU expenses, Ms Hautala considers that “We cannot demand openness and transparency from others, if those principles are not followed within our own institution. Secrecy around MEP’s expenses only damages the image of the European parliament and emboldens Eurosceptics.’ The Green Party as a whole is against such secrecy and all its MEPs will in future, if they don’t already do so, have to publish information regarding their use of GEA. British MPs, both Labour and Conservative, already publish details of their expenditure. As individual office expenditure goes, it may be insignificant and, as the ECJ identified, there is the question of proportionality. How many extra staff would be needed to police such accountability? Tom Harris pointed out in his excellent article that, in his view, IPSA was a costly mistake ‘borne of panic and a failure of leadership’. He also concludes that ‘democracy costs’ and that unfortunately those costs will continue to rise. He may well be right and if we ever manage to leave the EU this particular cost will thankfully not be our problem, but it will continue to be a problem for all those countries, people and politicians in the EU.

Mistrust in politicians is sadly the order of the day, so transparency (not secrecy) and light (not obscurity) on how public money is spent is going to be essential. Those politicians like the president of the EU parliament Antonio Tajani and his cronies on the ruling bureau who consider the privacy of the MEPs to be paramount, and those judges of the ECJ who concluded that campaigners had failed to prove that publishing information was ‘appropriate and proportional’ and that it was not for the court to consider the ‘shortcomings’ in the scrutiny of MEPs expenses, are failing to understand that the public are increasingly demanding accountability from those in power. Surely with technology playing an increasing role in everything, this should be achievable without creating too much extra admin and costs – particularly if MEPs themselves participate willingly and voluntarily in publishing the relevant data. Why, if this is public money, should the information be kept secret and private? It might even help those who wish to communicate with their MEPs – the whereabouts of their offices could be a good starting point.

Mistrust in politicians is sadly the order of the day, so transparency (not secrecy) and light (not obscurity) on how public money is spent is going to be essential. Those politicians like the president of the EU parliament Antonio Tajani and his cronies on the ruling bureau who consider the privacy of the MEPs to be paramount, and those judges of the ECJ who concluded that campaigners had failed to prove that publishing information was ‘appropriate and proportional’ and that it was not for the court to consider the ‘shortcomings’ in the scrutiny of MEPs expenses, are failing to understand that the public are increasingly demanding accountability from those in power. Surely with technology playing an increasing role in everything, this should be achievable without creating too much extra admin and costs – particularly if MEPs themselves participate willingly and voluntarily in publishing the relevant data. Why, if this is public money, should the information be kept secret and private? It might even help those who wish to communicate with their MEPs – the whereabouts of their offices could be a good starting point.