13 August 2015

Australia Murders Language in Revenge

By Chin Chin

With the current enthusiasm for plays written by Aeschylus and Euripides you would have thought that we would recognise revenge when we see it. How is it then that when the Sydney Morning Herald described the start of the fourth ashes test match as “pomicide” the term was not seen for what it was?

This extraordinary new word seems to have a Latin genesis. The Romans (who for the benefit of the Sydney Morning Herald were big users of Latin) used “caedere”, meaning “to kill” and the English language has borrowed it by adding the suffix “-cide” to indicate the killing or destruction of the thing to which it is added. Hence “patricide” means to kill one’s father; “fratricide”, means to kill a brother. “hereticide” means to kill a heretic. Taking things a little further, the suffix can also be used to denote the person who does the killing or destroying. So those who signed the death warrant of Charles 1 were known as regicides and the term “suicide” is used for a person who kills him or her self as well as for the act of killing. In 1886, the London Review used the term “the venerable birdicide” to describe the Ancient Mariner who, again for the benefit of the SMH, is best known for having shot an albatross.

Actually it all goes further than that and the suffix is also used to label the instrument by which the deed is done so that an “insecticide” is a chemical for killing insects, a “fungicide” kills people with beards and a pesticide destroys noisy and ill-mannered teenagers. All in all, then, this is a pretty adaptable suffix and English has made use of it in a flexible way. What the language doesn’t allow you to do, however, is to turn it all round by inserting, before the suffix “cide”, the description of the person doing the killing or destroying. Thus “insecticides” are used to kill insects. They are not chemicals with which malignant cockroaches can wipe out the human race. “Patricide” is committed by killing your father. If he gets his blow in first it will be “filicide” or, should he do so early enough, “prolicide” or “infanticide”.

That makes you wonder about “pomicide” which, on orthodox canons of construction, should refer to the killing of Poms and not the destruction of Australian batsmen. It can be confusing watching a test match but it seems unlikely that even the Herald’s sporting journalists will have concluded that a session in which Australia lost all their wickets for 60 runs was an occasion on which they can be described as having slaughtered the opposition. Two explanations spring to mind. The first is that there has been some sort of error. It is a possibility, of course, but unlikely as the newspaper concerned is a very distinguished one. The second is that the cutting edge of language has moved forward by a sudden quantum leap and that the suffix “-cide” is now being used in a new and different sense. That seems more likely. In practice a new word is used on the streets some time before it is admitted to the dictionary. Perhaps “pomicide”, with its revolutionary use of the suffix, is just in that in-between stage.

It is a nice theory but it won’t do. I’m sure that some streets in Australia are quite violent but it seems unlikely that the slaughter of Englishmen is now so commonplace that they have invented a special word for it. Perhaps things will change after the Ashes series but, as of the morning of 7 August 2015 when the “pomicide” headline appeared, it seems unlikely that the word was in street use. Where then can the Sydney Morning Herald have got it from?

The solution must, I think, lie in the study of human nature rather than the study of language. If something you really value is injured, and Australia’s reputation for prowess on the cricket field will have been severely damaged, then the instinctive reaction is to spoil something of value to the opposition. What do the English value? Why, their language of course. The dissolution of the monasteries in 1536 resulted in the destruction of the English artistic heritage. The monasteries were the centre of music as well so the nation needed a new outlet for its creative talents. It found it in language and the flowering of literature in the late Tudor and early Stuart periods were a direct result of that. The English language is a beautiful thing. An obvious target.

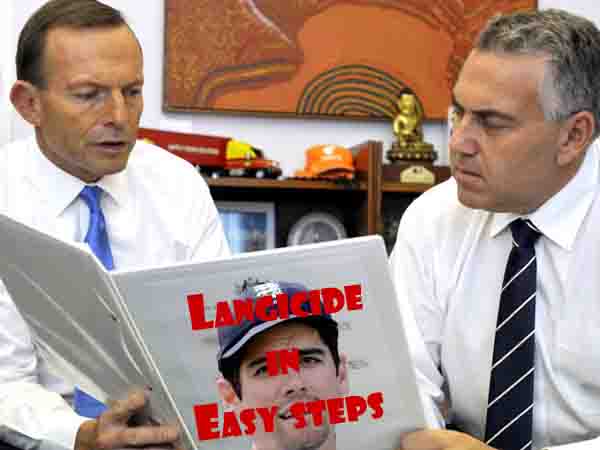

Imagine, then, the scene in the Australian cabinet when they heard that their batting had been destroyed. An appropriate revenge was needed and, as Australians are generally better at Greek than they are at Latin (after all they have hosted the Olympics), they probably began by looking at the revenge wreaked by Atreus on his wife’s lover, Thyestes.

”Yeah, cook their teams’ children in a stew and serve them up to their parents”, they will have said, corks bobbing merrily around their hats. An excellent idea on the face of it, but quite difficult to do from a range of 10,000 miles. No, something easier to implement was needed.

“What about sending a case of poisoned wine,” someone will have suggested. “There’s lots of Australian wine drunk in England and we could just add a little something to a case before we send it as a gift to the England dressing room”. A more practical idea this, but again there was a difficulty. Revenge is no good unless everyone understands what has been done. How could anyone be sure that the wine had been poisoned deliberately? People might just think that it was rather a rough vintage in which case wiping out the entire England cricket team could seriously conflict with the wine industry’s marketing message.

No, it had to be cleverer than that and also, to be really satisfactory, it would have to go beyond the team and upset the English nation as a whole. The answer was obvious. Murder the language! By now you won’t need Hercule Poirot to tell you that the Sydney Morning Herald was commissioned to carry out the dreadful deed.