05 October 2017

Soul Of A Nation

Tate Modern, 12 July – 22 October

Reviewed by William Morton

This exhibition showcases work produced by Black artists in the two decades commencing in 1963 when the Civil Rights Movement was as at its height. The political activity naturally stimulated Black artists to produce work reflecting it or in support of it. It is hard to realise that at that date Black artists found it difficult in the US to have their work displayed in established galleries. One response to this was to paint large murals and billboards with scenes of Black life. Photographs of some of these form a part of the Exhibition. Recordings of the voices of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X and other activists establish the mood.

The exhibition starts with some strong pictures relating to the Movement such as America the Beautiful (a sardonic reference to a famous patriotic song) by Norman Lewis, in which small Ku Klux Klan hoods and burning crosses in white are shown against a totally black background. There is Bobby Seale tied to a chair and gagged during his trial; there are paintings of Black leaders in bright colours which look like Byzantine mosaics of saints. One exhibit, Fred Hampton’s Door 2 by Dana Chandler, is a door riddled with bullet holes reflecting the shooting by the Chicago police of a Black Panther leader in his apartment. There are powerful graphics by Emory Douglas, the Black Panther’s Minister of Culture, which appeared in their magazine attacking the ‘pigs’ and showing children with guns.

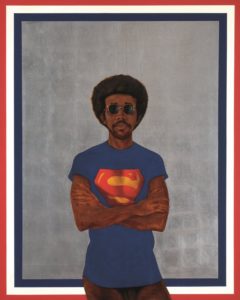

Some of the most striking paintings are by Bradley L Hendricks, who died earlier this year. His Icon For My Man Superman (Superman Never Saved Any Black People – Bobby Seale), used to advertise the Exhibition, is a wonderful depiction of a cool young Black man with attitude and naked from the waist down with a surround suggestive of the American flag. A self-portrait in the nude is similarly forceful and references an art critic who had described him as well- endowed (artistically). Then there is What’s Going On in which four Black men in smart white suits and hats and a naked girl stare into the distance. The title refers to a Marvin Gaye album considered a masterpiece of protest music. The Exhibition quotes Hendricks as saying that he did not consider himself to be speaking for Black people. His pictures seem to rather contradict that in that they give astrong sense of Black identity and pride. In the same room there is a simple but colourful and effective Warhol portrait of Muhammad Ali (? The only work by a White artist shown).

Although it perhaps tails off a bit towards the end with curiously shaped canvases and sculptures made of nylon stockings, overall it is an intriguing Exhibition. The depressing thought is that, if recent police shootings are anything to go by, the relationship between Black and Whites in the US remains fraught.

If you enjoyed this article please share it using the buttons above.

Please click here if you would like a weekly email on publication of the ShawSheet