14 September 2017

It’s Behind You

Surveillance – by Uber

by J.R. Thomas

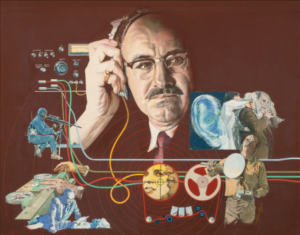

Gene Hackman as Harry Caul in The Conversation

Or in front of you; or above you; or all around you. Privacy is so yesterday. And that mobile phone in your bag or pocket so handy. But do you know who it is talking to?

Or in front of you; or above you; or all around you. Privacy is so yesterday. And that mobile phone in your bag or pocket so handy. But do you know who it is talking to?

Uber, the urban taxi service we all love has come in for a lot of brickbats recently, paying the price for becoming market leader and destroying those old ways of calling a black cab, or a yellow cab, or just your beat up local Mondeo with dubiously damp back seats. Bad behaviour on the part of Uber’s chief executive (now departed), an uncorrect laddish culture in its Californian head office, destroying local rivals by vicious undercutting, we naturally deplore; but we go on using it. So easy and convenient; those Uber apps connecting instantly with the nearest available ride, showing the estimated time of your journey, the name of your driver, the colour and registration number of his pristine car on its way to you. And when you get out, the app pays, even tipping the driver. But it doesn’t switch off once you have left your taxi and gone about your lawful occasions. The app carries on for five minutes, checking where you and your faithful mobile are off to. Into Sainsbury; to your office; to the wine bar; to the massage parlour, Uber knows. It helps, Uber says, improve the service next time.

Transport for London, which runs the capital’s public transport, has recently installed in many stations and in some tunnels wifi systems so you can now impress, irritate, or appal your fellow travellers with your conversations and thumb dexterity. But wifi works both ways. You may just be calling Aunty Mavis or cousin Nasir, or reading the Shaw Sheet, but TfL knows where you are, which station entrance you have used, and when you pop up somewhere else it knows that as well. It knows your shortcuts, your strange diversions; it knows where is crowded and where is empty. It knows your travel habits; and if you do some strange one-off journey to Ealing South that you have never done before, it knows. But, says TfL, do not worry, we are just improving your service, easing your transfer, getting rid of congestion and overcrowding, helping make your journey smoother.

Because one thing we can always be sure of, government and commerce are just here to help. Aren’t they?

One of the best films, maybe of all time, certainly of the 1970’s, though little known and overshadowed by its successor (even though most film goers did not realise it was a successor to anything; we’ll come back to that) was “The Conversation”. An early Francis Ford Coppola movie, powerfully displaying what we now expect as Coppola directional insights and film making skills, it starred Gene Hackman. Hackman was then little known but even if the public did not flock to see him this time, the film world recognised rising talent in this balding everyman actor.

Hackman plays Harry Caul, an IT specialist (microphones and tape recorders, this is 1974) running a surveillance business. He is hired to watch a couple and his team pick up some intriguing snatches of conversation between them meeting surreptitiously. But who are they? What are they talking about? Who is really paying to have them watched? And who are Harry’s watchers actually watching? Harry is by nature suspicious and paranoiac; but as the film progresses he realises that suspicion and paranoia can be key survival tactics. It is a film about power and the misuse thereof, about how we are not as free as we like to think we are (or at least as we thought we were in 1974), and about how you can never assume you are alone.

In 1998 Tony Scott picked up the theme in his “Enemy of the State”. Mr Hackman was back, as Harry Caul’s spiritual descendant Brill Lyle, with Will Smith as the innocent lawyer who becomes alarmingly inconvenienced by the power of technology, and confused as to exactly who is operating the machinery. Enemy of the State was intended as a blockbuster (and became one) with perhaps a few too many action packed sequences for some tastes, and certainly lacks the subtlety of The Conversation, but it plays successfully and unnervingly with the same themes. It was intended as a homage and a follow-up to The Conversation (it is clear that Hackman as Brill is effectively Caul twenty odd years on), and the point that those with resources can watch, monitor, and control those without is powerfully made. Indeed, word has it that the point was so powerfully made that the National Security Agency, the government agency depicted in the film but also the real life agency of surveillance in the US, was appalled – not just by the ruthlessness shown but also with the film’s insights into its capabilities and methodologies. So appalled it hired a PR agency to try to improve its standing amongst the public – and the nervous politicians on whom it depended for funding all that technology.

Twenty years on even the technology of 1998 looks ridiculously harmless – and clunky. Now spy cameras will fit in screw heads; every street and store and soap box on Speakers Corner has a video camera watching, recording, even listening. Buses and trains have them, as do many private motorists, cyclists with those odd fittings on their helmets. But that is the most benign surveillance. Your credit card records where you are and what you have bought there; your season ticket or Oyster card your journeys. Log on to Amazon to buy, say, a DvD of The Conversation; it may well offer you a deal if you buy Enemy of the State as well. And similar films, similar books, a poster of the movie. Every time you buy something, at Amazon or elsewhere, you provide information to the on-line store about yourself. What you read, what you watch, what you wear, what you eat; that you have a cat, four children (one of which your spouse does not know about), that you eat out a lot and drink too much. Your friendly cyber shopkeeper does not keep that to himself either; that is valuable material and soon that data may be sold and in the hands of others. Just wait until the police confuse you, an innocent happily married lawyer, with a bad man with an illicit video tape; your wife finding out that you spent part of the morning in a lingerie shop – but brought nothing home to her – will be the least of your worries. And then you are in the hands of the state; and Brill Lyle knows where that might end up.

“If you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear” is always the mantra of the reassuring security agency, or the politician who sees its reports. But most of us do have little things we do hide, or just prefer our private lives private and our secrets secret. We may prefer to choose what it is we are shopping for without wandering through a cyber oriental bazaar with wares thrust in our faces, our virtual footsteps pursued down the street. Plus that friend in our pocket, so handy, so compact, so powerful, so easy to use for so many things; all the time telling so many people just where we are and what we are doing.

Arguing against over-monitoring in an age of terrorism, much of it organised by technological means – or exploiting the weaknesses of technology – does often feel uncomfortable. There is of course a balance to be struck; though one suspects that the bad guys know how to vanish whilst it is the innocent that have electronic tails. What does not seem to add much to the security of us all is Uber watching your footsteps go round the corner; Amazon knowing you prefer Mozart to Brahms; John Lewis knowing your shirt size has gone up twice in two years. And remember:

Just because you are paranoiac doesn’t mean they are not out to get you

If you enjoyed this article please share it using the buttons above.

Please click here if you would like a weekly email on publication of the ShawSheet