12 January 2017

University Rankings and Free Speech

Universities and students past and present.

by Lynda Goetz

The old black and white photograph of 14 young men in bow ties was at first glance unremarkable – until you realised that this photo, taken on the occasion of Ken Clarke’s presidential debate at the Cambridge Union in 1963, contained no fewer than half a dozen people whose names would become familiar through their attainment of high political office. The reputation of Cambridge University pre-dates by many centuries the development of university rankings, of course, but by any standards that is impressive. However, that was not the only noteworthy aspect of Ken Clarke’s brief article promoting his new book ‘Kind of Blue: A Political Memoir’. The other thing which leapt off the page was his comment about his invitation to Sir Oswald Mosley to speak at the Union; “We all objected to his fascist beliefs, but he was a spectacular orator and I thought students should listen to views they didn’t agree with and challenge them.”

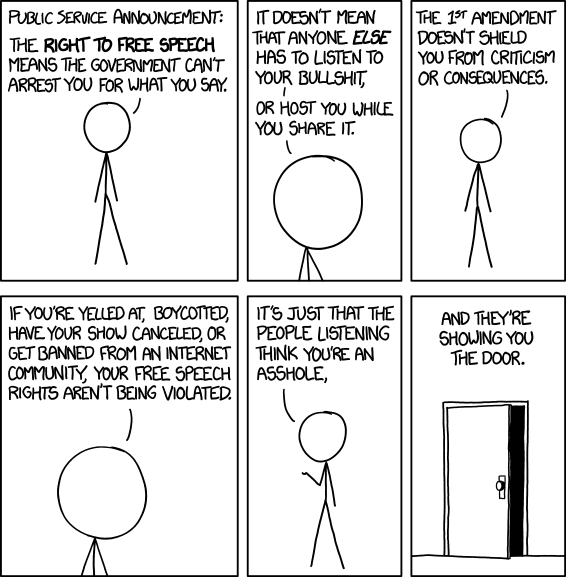

Ken Clarke did confess that he had a temporary falling out with Michael Howard over this controversy, but there was clearly no question then of anyone demanding Sir Oswald be ‘no platformed’. Students in those days, it would seem, were more robust. There are now concerns that if ‘student satisfaction’ is included as one of the criteria in a new ranking system proposed by the government in its new Higher Education and Research Bill, then university authorities will end up pandering to some of the ‘flakier’ student demands in order to secure a better place in the rankings. After a year which has seen a number of cases of students issuing an ultimatum (including unsuccessful demands for the removal of the Rhodes statue at Oriel college; the successful demand for the removal of a foundation stone laid by King Leopold II of Belgium at the Queen Mary University in London; the no-platforming of Germaine Greer; a demand within the last few days at the School of Oriental and African Studies -SOAS – that ‘white philosophers’ such as Plato, Aristotle and Voltaire be removed from the syllabus and so on), it seems increasingly clear that some universities are failing to hold a line against ridiculous demands by delicate ‘liberal activist’ or ‘regressive left’ students who cannot cope with any opposition to their own world views.

This is a subject that has been much in the news over the last year or more. It does not seem to be going away. Initially it appeared to be a rather crazy trend which we could safely attribute to American campuses. We could laugh at Yale students who wanted to purge the English department of the dead white guys making up its Major English Poets section on the grounds that it ‘creates a culture that is especially hostile to students of color’, or activists who demanded that their colleges provide ‘safe spaces’ for all sorts of minority groups, or demands to monitor and police acts of ‘micro-aggression’; that is until we found the same thing happening over here, culminating a few days ago in the demand by SOAS students for a philosophy course omitting most of the major philosophers – on the grounds that they were white.

The economist Baroness Wolf, quoted in The Telegraph, said, “This whole movement is a direct threat to academic standards and the ability of universities to stand up for free speech.” University rankings are themselves a relatively new phenomenon and like so much else came originally from America. In the old days, the reputations of universities like Oxford and Cambridge and the American Ivy League universities spoke for themselves. Whether or not this was simply a reflection of social elitism, their prestige clearly provided a beacon to attract the best students, best teaching and best funding.

It was one James McKeen Cattell, a psychologist, who at the turn of the 20th century started trying to evaluate the strength of universities by the numbers of eminent men of science in each university or faculty. Later attempts were based on the eminence of the faculties and their present reputation, rather than the number of eminent men in the departments. However, it was not until the media got in on the act that the whole rankings idea became part of popular culture. It was in 1983 that US News first issued a ranking table of American universities and from 1988 onwards produced an annual rankings table. International rankings are now popular. The first of these was produced in 2003 by Shanghai University – initially to compare Chinese with other world universities. The methodology of each rankings system differs and there is little agreement on any common method and no consensus as to how to evaluate excellence or even what that excellence is. The groundswell of discontent amongst the academics and universities is unlikely to be heeded, however, as politicians and public clamour for some form of visible evaluation of performance and cost effectiveness. Peter Smith, a British academic who teaches Modern World History in Mahidol University International College, Thailand, concluded in his YouTube video ‘A Short History of University Rankings’ that only very well-established and well-funded universities can afford to ignore the various rankings systems.

It is against this background that our government’s Higher Education and Research Bill seeks to put in place yet another ranking system so that universities ‘will be assessed according to their performance on student satisfaction, retention and graduate employment as well as other metrics yet to be developed whilst also drawing on qualitative institutional submissions and expert judgements’. (Times Higher Education: Higher education white paper key points). It is the emphasis on the subjective student experience, an entirely new element in any evaluation of university excellence, which is now causing some concern. Whilst methodologies may differ, none has included such criteria before. According to Baroness Wolf, “The student satisfaction measure is fantastically dangerous. The way to make students happy is not asking them to do any work, and giving them a high grade.” She added “This will reduce standards and undermine quality. I just think this is totally mad, and destructive of everything universities stand for.”

Professor Julia Black, interim director at The London School of Economics, pointed out that The National Student Survey (NSS), which was launched in 2005 and takes place annually and would be the basis for any evaluation of student satisfaction, should be treated with caution. “You should always engage with students, but their experiences change the whole time. Universities do have to challenge students and students may find that to be an uncomfortable process. It is beholden on universities to make sure students feel supported through that challenge.”

So in an era when populism is all the rage and everybody’s opinions on anything and everything can be so easily canvassed and all carry equal weight because we no longer believe in experts, how on earth are we to evaluate universities? Clearly when students are racking up quite substantial debts as a result of their time spent at university they need to feel that they have received value for money and that their experience has been worthwhile. Equally clearly some higher educational establishments are cavalier in their attitude to their students as they focus on research rather than teaching excellence. The Higher Education and Research Bill has a long way to go before it passes into law and already the amendments added are likely to prolong its passage through parliament. On Monday, the Bill in its present form was defeated in the House of Lords, 248 votes to 221. A series of amendments were proposed and it was pointed out that nowhere was ‘university’ defined. Perhaps before we agree on how we define and evaluate excellence, it might be important to agree on what constitutes a university?

If you enjoyed this article please share it using the buttons above.

Please click here if you would like a weekly email on publication of the ShawSheet