12 November 2015

Ban It (part 2)

I’m not going to argue about it, so shut up!

By Neil Tidmarsh

Last week I wrote rather jealously and wistfully about the power enjoyed by authorities in various advanced civilisations out there to simply ban whatever annoys or upsets them. Imagine my amazement and delight this week, therefore, to read that the idea is at last beginning to catch on here in Britain! And in our universities, of all places! There’s hope for the narrow-minded, intolerant, cowardly, lazy, stupid, over-sensitive and hopelessly subjective among us yet.

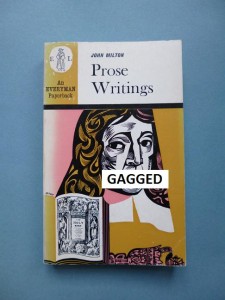

Universities, students and students’ unions all over the country are banning an increasing number of speakers from public discussions and debates. Any opinions which students don’t like or find uncomfortable are gagged. Books, lectures and articles which might disturb or frighten them will soon be censored with trigger warnings.

The universities of Essex, Cardiff, Manchester, Leeds, Warwick and Christ Church, Oxford – dictators, totalitarian states and authoritarians from all around the world and throughout history salute you! Wave those placards in proud protest, chanting “Down with freedom of speech! Down with tolerance! Down with the fearless battle for the objective truth!”

The brilliant thing is that the speakers and opinions being banned aren’t just the dodgy extremes which promote illegal and violent activities, but liberal crusaders like Peter Tatchell, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Christine Lagarde, Germaine Greer and Mary Beard. So the area permitted for debate and discussion is shrinking bit by bit until eventually it will be so small that there will be nothing left in it but consensus and agreement. At which point intellectual enquiry and development will no longer be necessary and everyone can go home and universities can be closed down and the argument about how we’re going to fund further education will become, well, academic. Genius. And instead of university, our young people can go to work for a pittance seven days a week, twelve hours a day in the Chinese-owned sweat-shop this country is sure to become if we no longer have intellectually-curious graduates trained and exercised in mental combat to create and maintain more interesting and better-paid industries. That is if there are any jobs at all in such a world. There certainly won’t be much political freedom left in it.

The key text which proposes tolerance rather than intolerance, debate rather than censorship, robust confrontation rather than over-sensitive withdrawal, objectivity rather than subjectivity, liberation rather than banning, is John Milton’s “Areopagitica” of 1644, ‘A speech for the liberty of unlicensed printing, to the parliament of England’. It has been the manifesto for freedom of speech for three and a half centuries, but it seems that it isn’t read much in universities these days – and indeed why bother with the challenging density of its arguments and the dazzling but unfamiliar riches of its seventeenth century prose if you don’t like arguments and are scared of the unfamiliar?

Milton wrote it at a time when new ideas and discoveries – scientific, political, cultural – were pouring into European society as never before. He realised that these new ideas had to be freely debated and openly examined in order to establish whether they were true or false. He believed that opposing views should be allowed to slug it out on a level intellectual playing field in order to establish who was right and who was wrong. He had no time for those who insisted that they were right but didn’t have the courage or the energy to prove it by arguing their case in robust debate, or the humility to risk defeat and be proved wrong.

“I cannot praise a fugitive and cloistered virtue, unexercised and unbreathed, that never sallies out and sees her adversary, but slinks out of the race where that immortal garland is to be run for, not without dust and heat.”

He also realised that almost nowhere in the world would this be allowed by the authorities, who inevitably felt that their power was threatened by new ideas. He had met Galileo soon after the Pope and the Vatican had banned the Italian from publishing his scientific findings, forced him to renounce his discovery that the earth rotated round the sun and not vice-versa, and placed him under house arrest. The fight for an open debate about the truth was ‘not without dust and heat’ indeed.

But Milton also realised that a society which did allow debate, did tolerate different ideas, did encourage a free and open pursuit of the truth, would have a huge advantage over those that did not. New ideas and useful truths would take it further and faster into a better future than all its rivals. And he believed that England – recently freed from the repressive authority of the Pope and about to challenge the repressive authority of the king – could be such a society, such a country.

“Methinks I see in my mind a noble and puissant nation rousing herself like a strong man after sleep, and shaking her invincible locks. Methinks I see her as an eagle mewing her mighty youth, and kindling her undazzled eyes at the full midday beam.”

And so it proved. The spirit of Areopagitica plunged the country into the heat and dust of the civil war from which it emerged clutching Milton’s “immortal garland,” the freedom to search for objective truths and tolerate different opinions. This liberty immediately embarked England on the scientific revolution, the industrial revolution, global trade, political stability, individual liberty and the rule of law while most other European countries were either stagnating under reactionary kings and intolerant popes or imploding in self-consuming spirals of revolutionary violence. By the nineteenth century it had given England (or, by that time, the United Kingdom – the English, Welsh, Scots and Irish embarking on a powerful experiment in a free, tolerant and robust engagement with each others’ differences) world supremacy. And in the twentieth century that supremacy passed to the USA, a country which had consciously embraced the spirit of Areopagitica with even more passion than the British and had deliberately used Milton’s ideas as the foundation stones of their nation.

But today – What’s that you say? You’re not going to give Milton a platform, because he’s just another dead white male? Because he was Cromwell’s secretary and therefore politically incorrect? Because he backed the regicides and so deserves a trigger-warning, as the blood of King Charles I might upset the sensitive and the vulnerable? So you’re not even going to let him speak? You’re not even bothering to argue with him? You’re going to gag him? Burn “Areopagitica”? Burn “Paradise Lost” because he gives Satan all the best lines? You’re going to ban him?

Well, I’m going to ban your ban. You say you’re going to ban my ban on your ban? Well, I’m going to get someone else to ban your ban on my ban on your ban…

Don’t laugh. We’re not the only ones indulging in this nonsense. This week, the European Court of Human Rights banned a French decision to ban a Turkish historian for banning the Armenian genocide from Turkish history books. What fun. Slapping bans on each other, closing the argument down, is certainly easier than debating the truth with each other, which takes courage and effort and intelligence, and certainly easier than tolerating each other’s differences, which takes self-restraint, empathy, respect and humility. And it also means that no one gets to be proved right or wrong. And so the troublesome and divisive reality of objective truth can be avoided altogether.

There’s only one problem. If you refuse to argue or debate with your opponent, peacefully and rationally, then sooner or later you’ll end up fighting each other. As Milton’s ideas found, when faced with a deaf, obdurate and authoritarian king, violence becomes the only way you can resolve your differ… Ow! That really hurt! Right – take that! And that..!