29 October 2015

Agincourt

How technology and terror still rule the day

by Chin Chin

You’d think we were in Monmouth, the Welsh town in which Henry V was born. It was as Henry of Monmouth that he was known and they certainly don’t let you forget it. The names Harry and Agincourt dominate the streets and attach themselves to everything from burger bars to hairdressers. “Would Sir like a Harry burger from the Agincourt Cafe?”, “Would Sir like venison? Shot by a local archer with a longbow.”, “Will that be a Brazilian, Madam, or our Henry V wax?”, “What about a plastic suit of armour to go on the mantelpiece?”

And now the madness has spread to south-east England. Put up the Times’s Agincourt poster to impress your French friends. Read an account of the battle written by a judge of the Supreme Court (yes, I kid you not). No one was allowed to forget that Sunday was St Crispin’s day, the feast of Crispin and Crispinian, twins martyred in about 286 who, if Saints care about how many people remember their day, must have been gratified in having it chosen both for Agincourt and for the Charge of the Light Brigade.

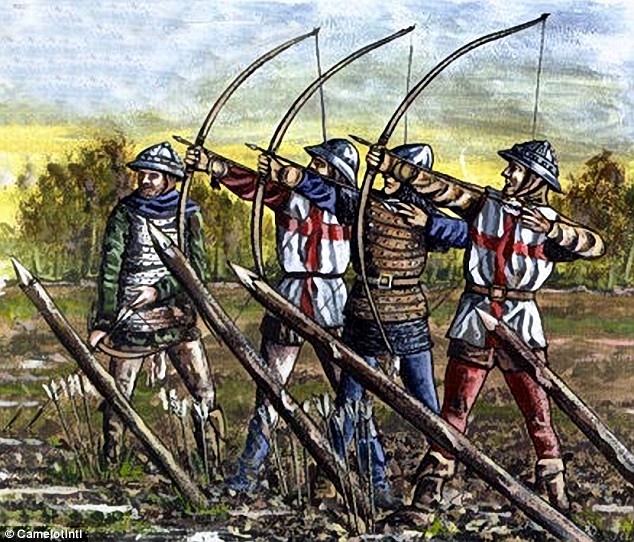

But behind the supplements, with their diagrams and pictures of weapons, and behind the tabloids, keen to celebrate a thrashing for the French, there is a serious question. How did Henry’s exhausted and outnumbered English army win by quite so big a margin? The losses say it all, somewhere between 4,000 and 10,000 on the French side: under 500 for the English. Now there was plenty wrong with the French command structure and the way in which they drew up their forces, but the scale of the victory points to something else, a difference in the technology employed by the two armies. In this case it was the decisive effect of the English longbows wielded by archers trained from birth to fire arrows at a much higher rate than could be achieved by continental crossbows.

If you look at the successful commanders of history, two features stand out. The first is technical superiority, either in armaments or in the way in which they were employed. The use of the long bow at Agincourt is an example of superior weaponry but Marlborough and Wellington based their success on new tactics. For example, Wellington’s innovation of meeting the French columns with a long line of troops, all of whom could fire, gave his men a huge advantage in firepower over the column where only those on the edge could use their guns. Or look at Guderian, whose revolutionary “Blitzkrieg” used tanks in an entirely new way and swept the allies back at the start of the 2nd World War. There are certainly no prizes for being behind technically.

The second feature is ruthlessness. Beneath the image of the chivalrous warrior king painted by Shakespeare, there lies another picture of Henry, that of the man who ordered the prisoners to be killed at Agincourt, that of the man who refused to allow the useless mouths of Rouen through the British lines so that they perished beneath the walls, that of a man who exacted retribution on enemies who stood out against him. What lay behind this is difficult to judge and Henry, clearly much loved by his subjects and a pious man too, certainly has his apologists. Perhaps the prisoners were seen as a threat. Perhaps his ruthless approach to those who opposed him saved lives through early surrenders. Still Henry seems to be a man who understood the use of terror as an instrument of war.

From this point of view little has changed since the early fifteenth century and technology and terrorism are still key instruments for the strategist. What is perhaps different is that, rather than being used in combination, they often form a counterbalance. Take the current war with ISIS as an example. On the one side you have a campaign run by religious zealots, terrifying civilians and using fear to unman the forces ranged against it. On the other you have the great technical superiority of the West whose waging of war is constrained by a public opinion that will not tolerate terrorist tactics. Then there are those who make use of both in varying degrees, Syria, Russia, and Turkey. It remains to be seen exactly how this will play out but there is one message that we can take away. It is easy to read of drone attacks and cruise missiles and come to the conclusion that things are unfairly slanted towards the West. That is true if you look purely in terms of armaments but put into the balance the fact that Isis can and does use terrorist tactics which would be quite unacceptable if employed by Britain and the US, and you see that the playing field is a little more level than might at first appear.