13 August 2015

The hidden benefits of private education

By John Watson

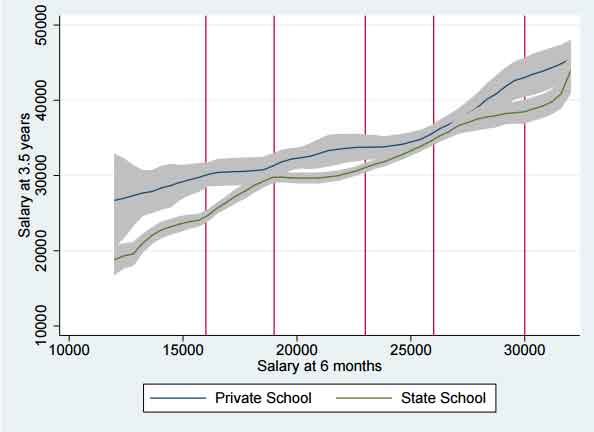

On 6 August 2015, Jake Anders of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research published a research paper which now appears on the website of the Sutton Trust. It is entitled: “Does socio-economic background affect pay growth among early entrants to high status jobs?” and it contains some interesting tables. One of those, and if you have a head for statistics you will find it at page 8, begins by comparing earnings six months after graduation, of those state school and private school pupils who get top jobs, defined for this purpose as “higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations”. The table shows that, on the basis of the sample used, the mean earnings for state school pupils stood at £22,735 whereas the mean for the privately educated was £24,066. So far, so not very surprising. No doubt it could be explained in terms of the privately educated getting slightly topper jobs than their state educated equivalents.

That, however, is not the point of the table. The real focus is on the position 3½ years after graduation. You might have thought that by then the advantages of a private education would have worn off a bit and that the differential would, if anything, have reduced. Not so, concludes Mr Anders. 3.5 years later the graduation the gap has widened, with state school pupils earning a mean salary of £31,586 and private school pupils earning £36,036. Whereas state pupils’ salaries have increased by just under 40%, the salaries of the privately educated have jumped by almost 50%.

Mr Anders estimates that half the increased differential can be explained by different types of university, courses taken etc. That leaves the other half of the increase unaccounted for and presumably down to more general factors such as articulacy, assertiveness and what are described as “wider societal factors”.

To the nonprofessional, the research looks very thorough but let’s move on to one of the recommendations. Remember, the central finding is that private school pupils have soft skill advantages which do not emerge at the recruitment stage but will become obvious later on. The reaction to that?

“It is crucial that employers have the tools and expertise to understand the social make-up of their applicants and recruits so that they can make fair judgements about their potential and provide tailored support to enable those from less privileged backgrounds to thrive once in employment.”

That is a little odd that when you think about it. Most employers make commercial judgements rather than fair ones and it seems from the table that the employer who hires from the privately educated is getting a hidden benefit. He will not have to pay for the additional support that would be required to enable the publicly educated employee to perform at the same level.

If you are concerned about social mobility, bringing this piece of research to the attention of employers seems to go in exactly the wrong direction. Surely the right reaction to the figures is to make every effort to work out how the private sector adds value and to try to replicate that across the state sector. Then we would have both fairness and efficiency together.

The whole idea that it is an adequate response to these sort of figures to encourage employers to support those educated in the state sector is repugnant. What about those who run their own businesses? Are they to be disadvantaged? What about life outside work? Is it right that the state pupil should be less fulfilled? No, the right answer must be to enhance the state education so that one day no one will be able to tell who comes from which sector.

The trouble with that strategy is that it is fraught with danger. Suppose, just suppose, that the soft skill advantages of private education turn out to conflict with some of the shibboleths of the state sector. Suppose they result from a competitive attitude to sport, a focus on homework or, worse still, on a certain amount of learning by rote. What would we do then? Would we change the approach taken in the state sector. Well, no, of course we wouldn’t. Aspects of that approach have been handed down as sacred writ from one generation to another. One could hardly give them up for a few children.