07 January 2021

Wagner’s ‘Ring’

Revealed and explained.

By Philip Throp

Wagner’s Ring cycle of operas has the reputation of being among the most cerebral of all operas, and the most difficult to understand, both in respect of the construction and patterns of its music and the meaning(s) of its storyline.

Without any technical music knowledge at all (we can’t even read music), my wife and I came to opera only in our early 40’s (perhaps unusually, not being Classical music-lovers particularly, although we were keen play-goers). But we started in the way most people come to opera; through Puccini. The reputation for difficulty of Wagner’s operas was the reason I jumped at the chance when I saw an advert for a series of ‘beginners’ lectures on Wagner’s Ring in a church in Bath, to be given by a music lecturer at Bristol University. Here was the chance of a lifetime to have assistance in understanding Wagner’s reputedly opaque operatic work. What could I lose? With hindsight, I have gained immeasurably.

From the off I was beguiled by the music of the recordings John (the lecturer) played, rushing home to my wife from each of them – and from a second series of John’s lectures – to tell her of my fascination. She entered into Wagner’s world with me, and for many years we always had something to talk about, discussing and debating with each other the myriad potential meanings and intentions of this cycle of operas.

The whole Ring cycle consists of four operas lasting 17 hours in total, the final one, Twilight of the Gods, lasting more than five hours. But in performance it all passes too quickly. My business partner, not an opera fan but intellectually curious, once asked me to tell him what the Ring was all about, this when we had half a day to wait for a connection at Hong Kong airport. The following year when he and I visited the Far East again, we were again delayed (this time for most of a day) at HK airport, and he said my explanations had so intrigued him, would I tell him the plot again? Duly encouraged, I’m going to try here to pass the torch on to you too.

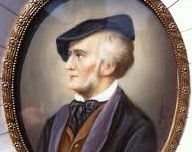

I have since researched Wagner at some length. It’s a great shame he didn’t stick to writing the operas and cut out writing rambling essays on culture and philosophy inspired from his gigantic appetite for reading. I consider him a real genius, but he was emphatically NOT a nice man. He certainly knew himself to be a rare genius and felt the rest of the world owed him. His operas were not commercially popular or even heard in public until very late in his life. He was born (probably illegitimate) to a poor single mother, he had no income, sustaining his expensive expectations by sponging on rich admirers one at a time, cuckolding them and once or twice stealing their wives from them completely. Oh, and of course constantly moving to avoid the debt collectors.

Wagner called the Ring his “Gesamtkunstwerk”, a (unique?) work of art which comprised “all” art forms. It’s a fact that everything in Wagner’s operas is his own work; unusually for an opera composer of the time, he devised the plot and wrote the libretti himself after voraciously reading and absorbing the atmosphere and poetic word-forms of the Nordic sagas, he wrote the incredibly innovative music, the stage directions, designed the scenery, promoted and directed the operas, even designed theatres where he intended the Ring should be heard.

The musical concept is totally innovatory in the history of opera. Before Wagner, operas consisted of a series of virtuoso staged arias, sometimes with spoken words or plain accompaniment to dialogue to advance the plot. Wagner invented the concept of music-drama, a much-devalued and misunderstood term these days as it also gets applied to popular musical theatre. With Wagner there are VERY few arias, the singers are not the stars of the show, it’s the music. The operas are what is called “composed through”; the music in the orchestra is continuous throughout, meaningfully symphonic in its constant but lengthy and gradual development, and plot-advancing in itself. Almost all opera written subsequently to Wagner will follow this model. Paradoxically perhaps, he stations his orchestra under the stage, out of sight of the audience, so that the orchestral sound indeed seems like a protagonist on the stage.

There are four operas: Rheingold, The Valkyrie (nb singular, not plural), Siegfried and Twilight of the Gods. There is one continuing story throughout, though there are back-references in each opera, making it feasible to view any of them out of order. Seeing them in order, however, makes manifest the gradually increasing complexity of the (philosophical) ideas and the thematic density of the music.

Before I relate the plot and its potential meanings, it is necessary to explain certain things about Wagner, so that I don’t interrupt the actual commentary too much.

Wagner became a giant of the Romantic movement, that movement in the cultural world which, in a recent television series, Simon Schama described as being originally a movement about political freedom starting with, or just before, the French Revolution. In 1849, Wagner had to flee from Dresden where he was Director of the Court Opera, to avoid arrest for his part in the May anti-monarchy uprisings in which he had played an active part.

He spent nine years in self-imposed exile for his own safety in Zurich, where he began to write the masterwork that was to become The Ring. It is here that Wagner built a theatre specially designed to stage ONLY the Ring Cycle. Wagner felt the concept of The Ring to be so beneficial for humankind that the audience for the nightly performances were to be admitted free, so as to address a mainly working-class audience. The theatre burnt down before any of his operas were performed there. It would be another forty years before Wagner, now under the patronage of an adoring and generous admirer in the person of King Ludwig of Bavaria, could design and oversee the building in Bayreuth of another great theatre built specifically for staging The Ring cycle. Seats in the Bayreuth theatre were definitely far from free of charge; Wagner could now indulge the recognition of his undoubted genius in, for example, a constant supply of silk dressing gowns delivered direct from London tailors.

The philosophies followed by Wagner at the inception of The Ring were firstly Proudhon (French) and secondly Feuerbach. Proudhon’s philosophy proposes anarchist revolution to overthrow the industrialised capitalist system which is coming into being and replace it with a back-to-the-land egalitarianism. Feuerbach offered a critical analysis of religion, a trend of thought which later led to Marx’s historical materialism.

These are the ideas in Wagner’s mind when he starts to write what became The Ring. I say “what became” because Wagner first wrote the libretto for an opera The Death of Siegfried; on concluding this he considered he needed to write the libretto of another opera to explain Siegfried himself, then another opera to explain the backstory of Siegfried’s parentage, and then another “opera” (Wagner always called it a “Vorabend”, an introductory evening) to set the origin of the (gold) ring itself, the principal symbol of the cycle, whose story runs through it from beginning to end. Gradually Wagner came to the conclusion that the saga was more about the fall of the gods, so that the story of the fall of Wotan (the king of the gods) becomes (arguably) the main focus of the story.

After extensive re-writing of the libretti, Wagner now set about writing the music. This was written starting with Rheingold and moving through the operas in the reverse order to that in which the libretti had been written. Started in 1848 and devoting himself entirely to this and no other operas, he had reached halfway through the third opera (Siegfried) by 1857. But he’d been immersing himself in many things, Eastern religion, mysticism, and, crucially, the philosophy of Schopenhauer.

Perhaps tiring of the strain and mental effort in setting the Ring’s music with its ever more complex web of thematic musical cross-references – but more importantly influenced to change the whole direction of progression of the Ring’s meaning – Wagner set aside the Ring (Siegfried) and wrote the most Schopenhauerian of all his operas, the mighty Tristan and Isolde, and then, seeking relief from the strain of that too, he attempted a ‘comedy’, The Mastersingers. These constitute a seven-year interruption in the writing of Siegfried.

More than a quarter of a century had passed since he’d first started writing the music for the first opera of the cycle, Rheingold. You don’t have to be musically savvy to hear and appreciate the gradually increasing density of the musical scoring and use of motifs during the first two and a half operas. But there was an even greater and astonishing leap in the stunning musical development when Wagner returned to composing The Ring.

While he was writing the rest of Siegfried and the whole of what was to become Twilight of the Gods, the intense influence of Schopenhauer’s philosophy on Wagner’s thought lead him to completely change the direction of plot and intended ending of The Ring. Originally, Siegfried (the unschooled child of nature, brought up in the forests with no human contact, “the World’s great hero”) was to succeed in using the power and influence of the ring to reverse Mankind’s trend of establishing a world of greed, power-seeking, materialism and industrialisation, and to supplant it with a more Nirvana-esque peace and spiritualism; now, however, he will be cheated of the ring and executed by the forces of evil as a result of his personal pride, and the ring will return to its original concealment by Nature in the depths of the river, once again guarded by the Rhinemaidens (its guardians at the start of the first opera of the cycle, Rheingold).

In subsequent articles for Shaw Sheet, I’ll take you through the saga of the four operas, and comment on some of its meanings and on Wagner’s innovatory use of leitmotifs in the music to give clues as to the meaning of the action as it unfolds. The Article in next week’s issue covers Das Rheingold and the Valkrie.