05 July 2018

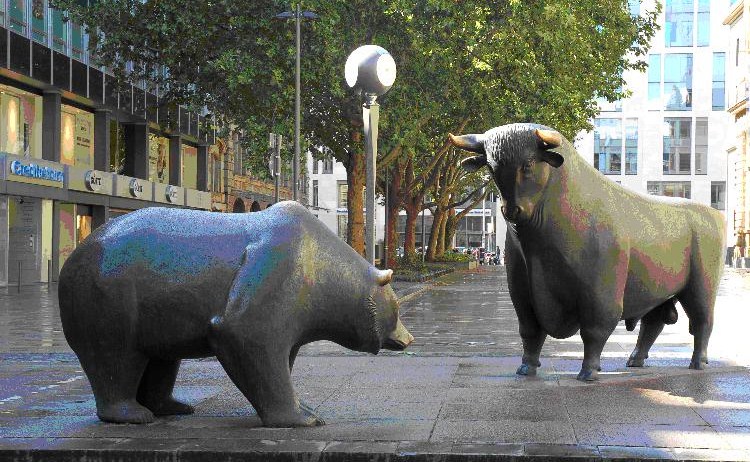

Don’t Sell (until you see the whites of their socks)

Central bankers are traders too.

By Frank O’Nomics

At the start of the year, many argued that we should await a “blow-off” top to markets before starting to sell. Such statements display arrogance, or the “greater fool” theory, and highlight the danger of holding out for too long.

At the start of the year, many argued that we should await a “blow-off” top to markets before starting to sell. Such statements display arrogance, or the “greater fool” theory, and highlight the danger of holding out for too long.

The signs that equity markets are either close to peaking, or have peaked, are building. The clarion calls for moving to safe-haven assets are growing, and it is time to once again examine whether we should join the ranks of the cautious.

We have argued before in these columns that, while markets looked overvalued on many standard metrics, the attraction of yield in an environment of perennially low interest rates due to unprecedented central bank support was worth holding on to for as long as possible. However, that central bank support has either stalled, started to be unwound or, in the case of Europe, has a timetable for tapering. Added to this are growing concerns over the escalation of trade wars, the resurgence of oil prices and political developments within Europe – especially in Germany and Italy. For the UK of course there is the added element of Brexit uncertainty, that continues to constrain business investment and hence any growth. It would be foolish to disregard any of these issues given that, even individually, they could prove critical in prompting a recession, either globally or nationally. However, it may be still too early to be heading for expensive safe havens. Global monetary policy is still exceptionally accommodative and the opportunity costs of sacrificing dividends and potential capital growth by heading for cash could still be very high.

There are clearly some major issues to worry about and markets are reflecting these concerns. The volatility of major indices is ample illustration of this, and many chartists and technicians are concerned that we have already started a downtrend. The greatest reflection of this has been in emerging markets, which are already down some 9% largely on trade war concerns. The other pointer that we may be starting to look at a recession comes from yield curves. While short dated US yields have risen to reflect a greater pace in rate rises, the level of 10yr bonds is still remarkably well supported. This, many are starting to argue, is a function of investors moving out of equities into supposedly “risk-free” assets, which heralds a recession.

Before moving on to the major concerns it is worth having a closer look at these gloomy indicators. First, the fall in emerging markets is not unusual given the volatility of this asset class and the fact that there are many with healthy profits from the last few years that they have been tempted to bank. Second, the low level of 10yr US bond yields is, in part, just a symptom of the cash flows that have been prompted by the bounce in the dollar. Any softening of the trade war issue should see a moderation in the dollar and a rise in bond yields.

Turning to the trade war issue, this is clearly a justifiable concern, but the markets are in danger of preempting the outcome of the process. If one regards the US stance as one of aggressive negotiation (that may in part be driven by the proximity of midterm elections) then assuming the outcome is dangerous. Most would argue that the imposition of tariffs is generally not conducive to trade and it is not unreasonable to hope that reason will prevail. In the interim, the process may help to decrease excessive corporate borrowing. Global growth projections of around 4% that prevailed at the start of the year still seem to be generally regarded as achievable – the “goldilocks” scenario of steady growth, helped by low interest rates and low inflation remains in place. As for the oil price factor, the rally has been disquieting but we are still a long way from the extremes of just a few years ago and oil producers do not have the power of old.

Turning to matters European; there is a risk that we confuse politics with economics. European growth does seem to have slowed, but not appreciably, and potential changes of government, imagined or otherwise, should not be assumed to prompt an end to any economic stimulus. The ECB may have announced an end to quantitative easing by the end of the year, but it has been buying Eur30bn of bonds per month, and any sales of assets could be many years away. Further, low interest rates also look like being with us for the foreseeable future given the profile of inflation.

The situation is not dissimilar within the UK. Rates may rise in August, but it will take some years before we hit a level that could not be regarded as accommodative, and, despite calls this week from some economists to start selling assets, any unwind of QE looks distant. The UK economy faces its worst year of growth since 2009, with the BCC now forecasting just 1.3%. This is not an environment where rates are going to be rising quickly. Clearly low growth, and low business investment may not be ideal for UK businesses, but a large proportion of the FTSE contains companies whose business is predominantly overseas. It is then global growth that we should be concerned by. Further, there is a case for looking at the reverse side of the Brexit debate. If business investment has been held back by the uncertainty, there is potential for a rush of investment when the issues are resolved. If this is hopelessly optimistic, consider the extent to which the government is trying to make up the shortfall in the interim. The extra money pledged for the NHS will have multiplier effects for the economy as that money is spent.

The last few years have seen central bankers move from being considered as practical academics to outright market traders looking to proactively influence the value of multiple asset classes. For this reason we should be waiting until they emerge as outright sellers of assets and not merely looking at glacial movements in what are still exceptionally low levels of interest rates. Money is cheap, and while it remains so the attraction of equities is undiminished.